What Happens When Bonds Lose Money

What Happens When Bonds Lose Money

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Early January is when many investors give their portfolios a checkup, and this year a sting awaits from the bond market. While equity returns dazzled in 2021, “safe” government bonds registered their first negative return since 2013.

Professional investors are of course accustomed to the idea that even so-called risk-free bonds lose money when interest rates rise—or are expected to rise. Those taking a diversified approach with their nest eggs are accustomed to think of Treasuries and high-quality bonds as conservative and safe investments that provide a consistent, if modest, positive return.

Except the sanctuary of government bonds cracked last year, with the Bloomberg Treasury index providing a total return of –2.3%. A broader exposure to fixed income that includes debt from high-quality companies, the Vanguard Total Bond Market Index Fund, lost 1.67% last year, its first down year since 2018—the last time the central bank raised its key overnight interest rate.

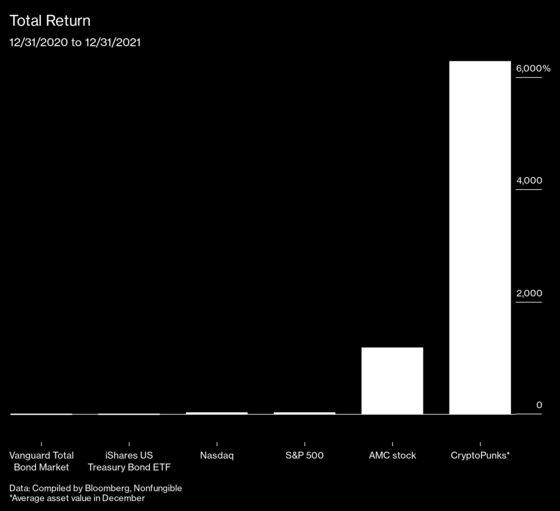

Once investors absorb the shock of a rare down year for bonds, some context is important. Equities are by far the dominant driver of long-term returns, because companies can increase their earnings over time. Negative years for bond returns are also more tolerable when equities perform strongly. Including the reinvestment of dividends, the S&P 500 gained 28.7% last year, and the Bloomberg 60/40 index, split between equities and bonds, returned 15.1%.

Still, the $22 trillion government debt market began 2022 on a bearish note, and some big fund managers expect Treasury bonds to remain a dead weight for a while yet. The Federal Reserve, focused on taming inflation, is expected to raise overnight rates toward 1% during 2022 and then above 2% by the end of next year. Strategists surveyed by Bloomberg News forecast higher Treasury yields by the end of 2022, with the 10-year yield reaching 2.04% and 30-year bonds rising to 2.45%. Rising yields mean falling prices, so if the forecasts are right, it would mark the first two-year losing streak for the Treasury index based on records dating from 1974.

“It is certainly conceivable that we see back-to-back negative years,” says Gregory Faranello, head of U.S. rates at AmeriVet Securities. “Investors need to find inflation-adjusted returns, and that is not being provided by the current level of nominal Treasury yields.”

Investors currently receive an annual fixed payment of 1.375% for owning a 10-year Treasury note. Not only is that now below the headline inflation rate, but it also provides little protection against a decline in the price of a 10-year Treasury. This was the story over the past year. While the Treasury index collected interest of 1.55% during 2021, that income stream was more than wiped out by a price change of –3.9% as interest rates climbed. In past eras, higher rates provided more protection against price losses, which is why the outlook for high-quality bonds looks particularly challenging at the moment.

A question for investors in the next couple of years is the nature of the post-pandemic recovery. Stubbornly elevated inflation may well lead the Fed to raise rates more aggressively, which could slow the economy and impair the performance of stocks. That’s one reason analysts and bond investors don’t expect 10-year and 30-year yields to rise significantly from current levels: Bouts of equity losses usually prompt an appreciation in the price of Treasuries, as money leaves stocks and seeks a haven. Alternatively, some policy tightening by the Fed may help moderate inflation and extend the business cycle, resulting in lower bond prices, while allowing companies room to keep increasing their profits and stocks to keep rising.

After double-digit gains in the S&P 500 for each of the past three years, some cautious investors may be taking money out of stocks. Others may think it’s prudent to get ahead of an extended bear market in bonds and increase their exposure to equities despite concerns about rich share price valuations. “It’s likely that some investors will see the disparity in performance of equities and bonds and tilt their portfolios further toward stocks,” says Todd Rosenbluth, head of ETF and mutual fund research at CFRA. “The patience of investors who own bonds will be tested as interest rates go up.”

For those investors with a longer-term perspective, owning Treasuries provides an important element of diversification—especially when U.S. equities sit at lofty levels that require robust earnings growth to validate their high multiples.

Bond managers seek ways to mitigate the pain when interest rates are rising. Some tilt their holdings toward floating-rate debt and seek to reduce rate risk by owning bonds whose prices are less sensitive to changes in interest rates, a characteristic known as duration. A bond fund with low duration will suffer less of a price decline when interest rates rise. This approach can help a bond fund navigate a bear market spurred by Fed hikes and then buy higher-yielding bonds once interest rates steady at new levels. “The expectation of rate increases from the Fed is reasonable and at some point Treasuries will look more interesting,” says Dan Ivascyn, group chief investment officer at Pacific Investment Management Co.

A period of rising Treasury yields that spurs negative returns in the near term may prompt institutional investors to buy long-dated bonds with the aim of diversifying their equity-dominated portfolios. “We have seen pension funds and insurers add to their fixed-income holdings when 30-year yields have risen beyond 2%,” says Faranello, who expects this pattern will repeat, because “we are still in a low global rate environment.”

The silver lining from another tough year for bonds is that higher yields also pave the way for better returns in the future and bolster the ability of Treasuries to act as insurance. “You want to look at bond holdings through the prism of a diversified portfolio,” says John Brady, managing director at brokerage R.J. O’Brien. Although he doesn’t rule out another year of losses for bonds in the region of 2%, Brady says: “Equities can register bigger losses than bonds.”

Read next: Green Bonds Tap Small Savers to Finance the Climate Transition

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.