Boeing and Airbus Are Launching Cargo Planes That May Face Crowded Skies

Boeing and Airbus Are Launching Cargo Planes That May Face Crowded Skies

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In recent years, when the world’s air carriers, aerospace manufacturers, and leasing companies gathered for the Dubai Airshow, the seemingly endless appetite for new planes shown by homegrown carrier Emirates Airlines and its Gulf competitors has gotten much of the attention. When this year’s show opens on Nov. 14, the spotlight will be on air freighters.

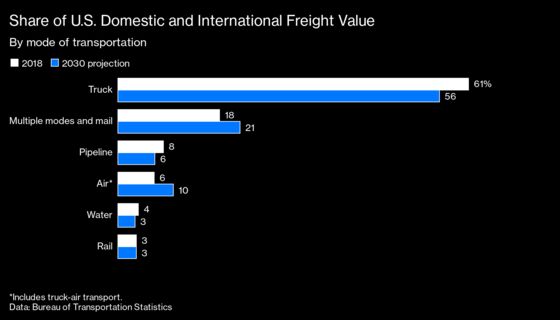

Because of the dramatic growth of e-commerce, the pickup in demand for both consumer and industrial goods as the pandemic eases, and supply chain turmoil that’s shown the downside of total dependence on ocean shipping, cargo carriers and logistics companies are turning to air freighters. These behemoths can quickly transport huge amounts of freight while bypassing port tieups, shortages of ocean containers or rail cars, and the current dearth of long-haul truck drivers. And aircraft owners are eager to add more of them to their fleets because the prospects for freight growth are encouraging. Plane lessor Avolon Holdings Ltd., for example, forecasts air cargo revenue will reach $150 billion this year, with traffic doubling over the next 20 years.

In Dubai, Airbus SE will be chasing customers for a cargo version of its A350 widebody passenger plane. Boeing Co. is also preparing to unveil the initial deal for an all-cargo version of its 777X widebody. But the announcement could come outside of the airshow if an expected launch customer, Qatar Airways, skips the event because of geopolitical tensions. Both planemakers have been schmoozing the same small circle of potential buyers, a group that includes FedEx, Lufthansa, Singapore Airlines, and DHL, according to people familiar with the efforts who asked not to be identified as the talks are confidential.

Just about every airworthy cargo craft has been pressed into service to meet surging demand for airborne shipping. Cargo titan Atlas Air Worldwide Holdings Inc. has snapped up 11 out-of-production 747-400s this year. And Amazon.com Inc. is shopping for used long-range cargo versions of Boeing’s 777 and Airbus’s popular A330 widebody, according to people familiar with the matter, the latest evidence of the e-commerce giant’s ambition to move products across borders itself.

Leasing companies are buying used passenger planes that can be stripped of their seats and overhead compartments and converted to freighter service. Last month, Avolon announced it will work with Israel Aerospace Industries Ltd. to convert 30 Airbus A330 passenger widebodies for use as freighters that will enter service from 2025 to 2028.

The sudden demand for aging behemoths like the 747 and the three-engine McDonnell Douglas MD-11, another large freighter spared from the scrapheap, creates uncertainty for the jets that are supposed to replace them. Boeing has already broken its record for annual freighter sales in 2021 and is looking to give lift to struggling 777X sales by launching a freighter version of the passenger jet. And Airbus is angling to take a slice of the market Boeing has long dominated by positioning its A350F cargo plane as an emissions-friendly choice that saves on fuel costs. Both could use these boosts at a time when the pandemic has slowed sales of large passenger airliners.

Yet there’s no guarantee the demand will still be there when the new planes arrive in a few years, after supply chain wrinkles are ironed out and travelers are once again trekking across the globe—with plenty of extra cargo space inside the bellies of the passenger planes they’ll take. Airbus and Boeing may face a glutted market, especially if leasing companies crank up programs to convert more passenger jets into package-haulers.

“We see strong freight demand today and for the foreseeable future,” says John Plueger, chief executive officer of Los Angeles-based Air Lease Corp. “But at the same time, a lot more airplanes are going to be flying in three or four years’ time.”

For years, dedicated freighters had lost ground to passenger aircraft carrying goods along with people. Boeing’s largest twin-engine jet, the 777-300ER, can carry 396 travelers on its main deck and the cargo payload of a midsize freighter down below. But with Covid, the drop in flying reduced such belly-freight capacity to a fraction of 2019 levels.

Danish container-shipping giant A.P. Moller-Maersk just ordered its first Boeing 777 freighters for an expanded foray into air cargo. And young and cheap 777-300ER and Airbus A330-300 airliners are being bought by aircraft lessors, hedge funds, and other financiers for cargo conversions as their leases expire.

Interest in conversions is so strong that existing slots to retrofit them are booked through 2025, says logistics consultant Brian Clancy. That’s a concern for Air Lease as it studies whether to create its own freighter program. “I don’t know what a normalized world is anymore, to be honest,” Atlas CEO John Dietrich said on an earnings call this month.

At the Dubai show, Airbus will be closing in on initial orders for the A350F, according to people familiar with its plans. Those briefed on the jet describe a formidable market entrant with a 109-ton payload and the range to cruise the Pacific Ocean.

“We came to the conclusion with our customers that the A350 is a fantastic platform for a freighter version,” Airbus CEO Guillaume Faury said in October. The jet’s arrival will be timed to meet “the wave of replacements that is in front of us in 2025 onwards with the new regulations on carbon emissions.”

Airbus doesn’t have to sell a huge number to claim success, according to Agency Partners analyst Sash Tusa. Logging 10 orders annually, or 20 in a good year, is enough to change the economics of the underlying A350 program. “It’s been a glaring gap in Airbus’s portfolio not to have a freighter,” he says.

Airbus’s plane is expected to reach customers around mid-decade. It will face competition from repurposed 777 passenger models that are due to enter the market shortly, offering similar capacity and reliability for less than half the $160 million going rate for a new freighter, according to consultant Stephen Fortune.

A rebound in belly cargo in passenger planes could help preserve market equilibrium, says George Dimitroff, head of valuations for Ascend by Cirium. As airlines bring back their widebody passenger fleets, freight prices should drop. That will cut into the profitability of older, fuel-guzzling freighters, eventually forcing them out of the system, he says. Cirium’s database shows that 523 cargo planes now in service are candidates for retirement, about half of them older-generation 747s.

“There’s lots of room for modernization,” says Tom Crabtree, a Boeing regional director of air cargo. “And there’s going to be increased pressure on the operators of older aircraft for more efficient or modern equipment.”

But while new emissions rules that could ground many older freighters are set to take effect by the end of the decade, regulations can change. Boeing has already petitioned the Environmental Protection Agency to delay the rules’ application to its current 767F widebody freighter program, arguing that financial uncertainty caused by the pandemic warrants more time being needed to upgrade or replace the program. And airframe makers sometimes simply misread demand, as Airbus did with the now-ended program for its mammoth A380 double-decker jumbo jet, which saw orders shrivel as international carriers lost interest in flying huge planes in their hub-and-spoke networks.

One of the forces fueling the conversion boom is the large number of cheap used planes. The manufacturers pushed widebody output to such heights last decade that “both the A330 and 777 have seen colossal collapses in market value,” Dimitroff says. A Boeing 777-300ER that cost upwards of $150 million new a decade ago can be picked up for $20 million to be retrofitted as a package-hauler.

Is a similar glut looming for dedicated freighters, as new plane prices will likely be many multiples of the cost of used jets? “I’m not sure I want to label it as a bubble,” Dimitroff says. “It’s a potential risk of medium-term oversupply, but not something that can pop overnight.” —With Siddharth Philip, Kyunghee Park, and Ryan Beene

Read next: Highly Paid Union Workers Give UPS a Surprise Win in Delivery Wars

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.