Bobby Bonilla and the True Story Behind Baseball’s Most Notorious Contract

Bobby Bonilla and the True Story Behind Baseball’s Most Notorious Contract

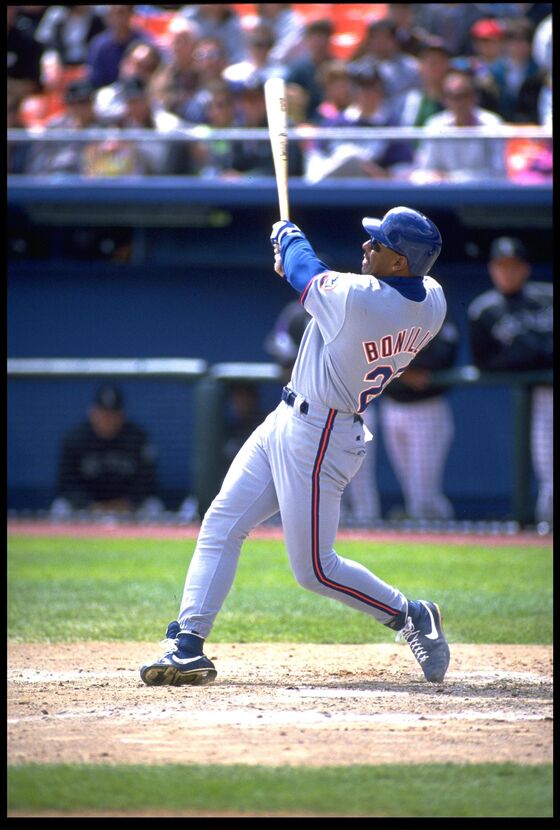

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- An oft-forgotten fact about the Bobby Bonilla era with the New York Mets is that there were actually two Bobby Bonilla eras. The first one began in December 1991, when Bonilla, then 28 and a four-time All-Star with the Pittsburgh Pirates, signed a five-year, $29 million contract—Major League Baseball’s most lucrative ever up to that point—to move to Queens and anchor the Mets offense.

The Bobby Bo who arrived in New York fresh off back-to-back National League East titles and back-to-back top-three MVP finishes was sunny and smiley and beloved—a big teddy bear, here to rescue the team that he and his surly co-star, Barry Bonds, had been brutally dismantling. Bonilla seemed like the perfect antidote to the PTSD from the Mets’ post-1986 World Series decline. Instead he became the face of what Mets beat writer Bob Klapisch dubbed “the worst team money could buy”: the 1993 Mets, 59-103, a record that doesn’t come close to capturing how disgraceful they were in the flesh. Eighteen months later he was gone in a trade to Baltimore. And good riddance, too. Good riddance all around.

So naturally, three years later, in November 1998, the Mets reacquired Bonilla in a trade with the Florida Marlins. The circumstances behind the holiday that Mets fans have come to know as Bobby Bonilla Day transpired at the end of Bonilla’s second stint in New York. Which is to say, the first Bobby Bonilla era was such a generational failure that the Mets refused to rest until they had topped it.

Even though he was 36 in 1999, and coming off an injury-plagued season, Bonilla returned to New York expecting to start. He did not. In fact he barely played at all, appearing in only 60 games and batting just .160, prompting him to declare that there would be “fireworks in the millennium” if he didn’t start in right field during the 2000 season (assuming the Y2K bug didn’t end the universe at the stroke of midnight, which it didn’t).

This was bound to be a problem, because the Mets had no intention of starting Bonilla in right field in 2000. Either way they were stuck with his $5.9 million contract, which was a ton of money for a reserve outfielder in 2000. In that moment the Mets would have done almost anything to give it to a really good pitcher and not Bobby friggin’ Bonilla.

Dennis Gilbert, Bonilla’s agent at the time, had Mets ownership by the throat. They could either pay Bonilla to poison their clubhouse next season, or they could pay him to go away quietly. Gilbert says the Mets approached him first and that authorship on a contract like that is impossible to untangle. “It wasn’t a five-minute call, put it that way,” he said with a laugh during an interview via FaceTime from one of the gardens on his estate in Malibu, Calif. He’s cagey about who had the original idea for the arrangement, but it was pretty clearly his. Soon after this deal, he went back to the insurance business because, he told me, there’s way more money in it than representing superstar professional athletes. Evidently he is right.

In any case, the idea could only have come from the mind of an insurance salesman: What if we defer the remaining money on Bonilla’s deal for a really long time, like a decade, and until then you don’t pay my client a cent—but then you start cutting him a big check every year for a much longer period of time? Like, say, 25 years. The Mets could spend Bonilla’s $6-ish million however they wanted, and then when he was in his 40s and retired and maybe his bank account could use the fresh influx, he and the Mets would be back in business together.

They haggled a bit on terms, and here’s where they landed: Bonilla leaves for nothing, now, as in, right this minute—GTFO—but starting in 2011, the Mets agree to pay him precisely $1,193,248.20 every July 1 for 25 years, until 2035, when he would be 72 years old. For the rest of his life, basically. That’s a grand total of $29.8 million, which is a lot more than $5.9 million. In exchange for waiting a decade to collect a penny, he was asking for an additional $24 million. It was an easy call for the Wilpon family. Their investment portfolio was booming. Their money guy was killing it. They could free up room in their budget and go get their front-line starter, and all they had to do was bankroll Bonilla’s retirement.

The Mets said: Where do we sign?

Bonilla said: Where do I sign?

And that’s how July 1 became, for Mets fans, a day which shall live in annuity—sorry, infamy. Annuity infamy. There’s no parade, not even a barbecue. It’s a holiday we celebrate with a communal sigh—you know the one—and maybe a votive on big anniversaries. (Like this one: Happy 10th anniversary, Bobby Bonilla Day.)

“Bobby Bonilla Day really should be a parade for his agent,” late-night host and lifelong Mets fan Jimmy Kimmel told me. “I hope whoever has to sign that check now—I hope it’s done electronically. I hope it’s a direct-deposit situation because I can’t think of too many things more painful than that.”

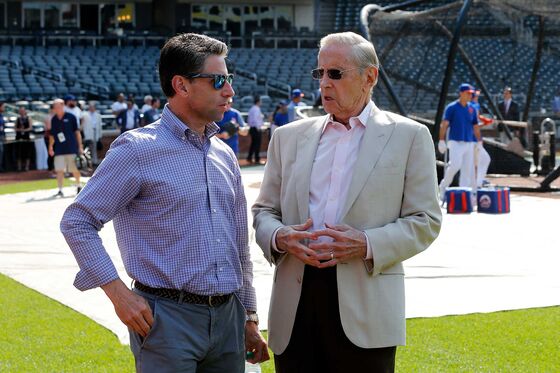

Last year’s bizarro, Covid-shortened season didn’t begin until July. But when the 2021 season starts April 1, as it’s scheduled to, it will be a particularly joyous spring awakening for Mets fans. Last fall the Wilpon family, who’d owned the team outright since 2002, sold it to billionaire hedge fund manager Steve Cohen for more than $2.4 billion, bequeathing Mets fans with the wealthiest owner in baseball and ridding us of the people responsible for the most infamous contract in pro sports.

Now that the Wilpons are gone, though, and the coast is clear, it’s time to reveal the hilarious truth: The deal worked beautifully for the Mets. It was one of the franchise’s savviest and most successful transactions. It paid instant dividends, triggering moves that led to a World Series appearance in 2000 and a deep postseason run in 2006. And yet that same contract has become a shining symbol of the cloddish Mets, a blunder of such epic proportions that fans have memorialized it with a sarcastic holiday. Somehow the Mets managed to get it wrong even when they got it right. They blew it, even though they nailed it.

With the savings created by the deal, the Mets were able to trade for Houston Astros ace Mike Hampton, who had just gone 22-4 and finished as the Cy Young runner-up, and absorb the cost of his contract’s final year: $5.75 million. Hampton had a strong year for the Mets (15-10, 3.14 ERA), and then he won the National League Championship Series MVP, pitching 16 shutout innings, striking out 12, and recording two of the Mets’ four wins over St. Louis. Hampton never liked New York, though, and he couldn’t flee the city fast enough. Barely a month after the 2000 Subway Series (a loss to the Yankees), he signed a rich free-agent deal with the Colorado Rockies because, he said, he and his wife preferred Denver’s public schools.

Hampton’s departure via free agency gave the Mets a gift, though: a compensatory pick in the upcoming MLB draft—the 38th overall in 2001—which they used to select David Wright, a third baseman from Norfolk, Va. By the time he retired in 2018, Wright had become the Mets’ all-time leader in just about every offensive category, and even more impressive, he managed to spend almost 15 years playing in New York City without ever once being dislikable.

Nothing about this Bonilla contract seems so bad so far, right? No talent squandered, no flotsam acquired in return. Just a rich family’s pocket change. Who cares? It’s not your money. Most accounts of the Bonilla deal describe it as a bold innovation gone awry, but it wasn’t in either respect. It was just an annuity. (Technically, Gilbert clarified for me, it was “nonqualified deferred compensation.” Annuities pay out for life.)

In fact, Bonilla received a similar, smaller arrangement from Baltimore that kicked in before the Mets deal. Did you know the Mets are still paying former outfielder Darryl Strawberry, too? He gets $1.6 million annually. And pitcher Bret Saberhagen? Sabes still gets a $250,000 check from the Mets every year. Two-time Cy Young Award winner Jacob deGrom has a similar postcareer bounty built into his current contract with the team. By now it’s standard operating procedure, a way for players to turn brief athletic careers into a lifetime of paychecks. And no matter how you slice the interest, the difference between $5.9 million upfront vs. $28.9 million spread out over 25 years is more than worth it for a World Series appearance, and almost two. So how could a deal that not only worked, but worked kinda perfectly, gain immortality as perhaps the Mets’ greatest blunder?

The answer lies in one, superimportant fact that the Wilpons didn’t know at the time, even though, according to prosecutors, they should’ve. And while it would be another eight years before any of us learned the truth, it was already true in 2000 when they promised Bobby Bo all that money: The Wilpons were broke.

In December 2008, less than three months after the Mets choked away a playoff berth for the second straight season—a déjà choke—a team of FBI agents slapped handcuffs on the Wilpons’ longtime friend and trusted financial adviser, Bernie Madoff. And because investigators suspected Fred Wilpon and his son, Jeff, might’ve been co-conspirators, they had to spend the next two years proving that they weren’t guilty, just stupid. (The Wilpons were never charged with any wrongdoing.) And right after that—July 1, 2011—is when the back end of their deal with Bonilla kicked in. When they were hanging on to the Mets franchise by their fingernails. If Bonilla’s paydays had kicked in earlier, say in 2006, when the world believed the Wilpons were solvent, no one would’ve noticed. Instead they had to start cutting $1.2 million checks to a 48-year-old who’d been retired from baseball for a decade when they could barely afford to field a team.

Bonilla grew up a mile from Yankee Stadium in the South Bronx, which means that he grew up a Yankees fan, but also that he grew up in one of the most underserved parts of New York City during one of its most hopeless periods. His neighborhood was smack in the middle of the NYPD’s 40th Precinct, notorious for its bloodletting. He played sports 24 hours a day and taught himself to switch-hit by pretending to be the Yankees’ Chris Chambliss from the left side and the Mets’ Tommie Agee from the right side. That’s how he got out.

“I’m the type who pinches himself every day,” he told the Los Angeles Times when he was 25 and still with Pittsburgh and about to play in his first of four straight All-Star Games. “I mean, people talk about the pressure of playing in the big leagues, but where’s the pressure compared to growing up in a ghetto and looking for ways to get out? I’m talkin’ about houses burning and people starving, and I’m supposed to be tremblin’ playing the first-place Mets or [the] Dodgers? I’m having the most fun I’ve ever had. Sports has always been my release. I’d turn on the news as a kid and couldn’t wait for [sportscaster] Warner Wolf. How many murders can you put up with in a day?”

Jim Leyland, his manager with the Pirates, a soft-shell crab who puffed cigarettes in the dugout and once got into a fist fight with Barry Bonds, couldn’t quit gushing about Bonilla. “I’ve never seen him down,” Leyland told the Times. “I’ve never seen him pout or panic. You can’t tell if he went 0 for 4 or 4 for 4. He always comes to the park in good spirits.”

Was everyone in Pittsburgh wrong about Bobby Bonilla? Or were we?

“He loved baseball as much as anybody,” said Gilbert, Bonilla’s former agent, as he power-walked a loop around his estate. “His first five years in the major leagues, this guy’s an All-Star, and he’s playing winter ball [during MLB’s offseason]. People don’t do that.” Coming home, though, turned out to be more of a curse than a blessing. Bonilla assumed it’d be a love affair from Day 1. Nope.

“There was a lot of pressure there,” Gilbert said. “It started from the time the negotiations were starting. I mean, here’s somebody who grew up in New York, and his family really wanted him to play in New York, and it’s really tough. He left at least a dozen tickets every night at the ballpark for his family.”

It’s hard to get a nuanced answer from Gilbert about anything other than insurance, but what came next surprised me, not just because of the admission itself, but the acknowledgment of how self-evident it had become: “A lot of people can’t play in New York,” he said. “A lot of people don’t perform.”

Like so many splashy free agents before him and like so many since, and not just for the Mets, Bonilla had an awful first season in New York. In this case the Mets had overlooked the degree to which he’d received easier treatment from pitchers because they feared the next batter, Bonds, so much more. Now Bonilla wasn’t nearly as “protected,” to use the baseball term, with Howard Johnson behind him in the order. Now pitchers were going straight at him.

His average slumped from .302 in 1991 to .249 in 1992. He had no protection, not in the lineup, not in the dugout, not in the front office. Bonilla, though, had the fat contract, and in 1990s New York, there was no juicier target than a guy making big bucks on a bad team. The competition to sell newspapers was brutal, lucrative, and often unscrupulous. Pouring gasoline on fires was a job requirement.

Bonilla wouldn’t talk to me. He works for the MLB Players Association now as a special assistant for international operations. He’s never said much on the subject of his contract, and it’s clear that he’s said all he has to say. He thanks God, he thanks Gilbert, sometimes he says it’s a beautiful thing, and then that’s that. No more questions, please. Most Mets fans assume he’s ecstatic, that he wakes up every morning with a mirthy chuckle.

“I don’t know, I’m guessing he feels good,” Gilbert told me with some mirth of his own. “He gets a check.”

This is just a guess, but I doubt he feels all good. I don’t know him, obviously, but I don’t think Bonilla takes any pride or sees much humor in Bobby Bonilla Day. I’m sure he likes the check—annual $1.2 million checks are indeed a beautiful thing. But there’s an implicit insult buried in there that Bonilla doesn’t deserve the money, that it’s being wasted on him, that maybe the Mets were rubes, but he’s still a grifter.

He was a six-time All-Star. He batted over .300 three times. He hit almost 300 home runs in his career. I’m sure he’d prefer to be remembered for his record on the field, rather than those annual checks. Because once you’re done with baseball—once any of us are done with anything we’ve put everything into—all that’s left is your name.

Adapted from So Many Ways to Lose: The Amazin’ True Story of the New York Mets—The Best Worst Team in Sports by Devin Gordon, to be published on March 16 by Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.