Blue-Collar America Braces for Another Devastating Recession

Blue-Collar America Braces for Another Devastating Recession

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Located a little over two hours due east of Dallas toward the border with Louisiana and a world away from the bustle of New York—or Wuhan—Lone Star is a pocket of rural Texas that’s so far managed mostly to avoid the Covid-19 outbreak. According to state data, just one case had been reported in all of Morris County as of April 1. The town, which has a population of about 1,700, isn’t doing as great a job, though, of escaping the impact of a U.S. economy tumbling into what threatens to be the deepest recession in generations.

Faced with declining orders and no clear idea of when things might change, United States Steel Corp. informed state authorities on March 23 that it plans to shut down its mill in Lone Star in May, putting many, if not all, of the 600 employees out of work. The facility turns out steel pipe for an oil industry that’s retrenching in response to a sudden collapse in crude prices.

“Anytime something like this comes up—people down here rely so much on oil price and the market—everybody gets scared,” says Trey “Tiny” Green, the 6-foot-9-inch, 315-pound president of United Steelworkers Local 4134, which represents hourly employees at the plant. “We’re in the infancy of trying to console and talk to our members on what the future will bring.”

If there is any consolation to be had, it may be that the steelworkers of Lone Star aren’t alone in the U.S. in 2020 in confronting a daunting downturn and uncertain future. Across the nation, what President Trump had been hyping as a “blue-collar boom” going into November’s election is quickly turning into a blue-collar bust.

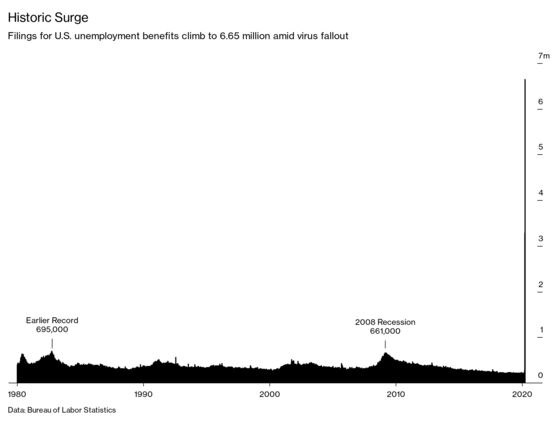

Forecasts by Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and others of an historic economic contraction in the months to come point to some 20 million jobs being lost by July, pushing the national unemployment rate into the midteens. The job destruction is happening in waves. Many of the record 3.3 million Americans who filed unemployment claims in the week ended March 21 worked for hotels, restaurants, and other service businesses that shut down in compliance with government orders to limit the spread of the coronavirus.

But increasingly the data are showing that America’s factory workers haven’t been spared. New unemployment claims for the week ended March 28 totaled 6.6 million, with many of the layoffs coming from manufacturers shutting down plants in response to rapidly shrinking order books or from pressure from unions concerned about the health of their members. Even before the worst layoffs took effect, the U.S. had lost 18,000 manufacturing jobs in March, new payrolls data released Friday showed. An estimated 623,000 auto and parts workers are on furlough, according to Kristin Dziczek, vice president of industry, labor, and economics at the Center for Automotive Research in Ann Arbor, Mich., a figure that represents 80% of the industry’s total hourly workforce.

From the Texas oil patch to traditionally blue-collar states such as Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin to newer ones including Tennessee, the U.S. industrial economy is embroiled in a slowdown that to managers and union reps already seems likely to be deeper than the one the country endured more than a decade ago.

Some of the impact—maybe even a substantial amount—may be offset by the roughly $2 trillion economic rescue plan Congress approved on March 27. Manufacturers such as General Motors Co. and Ford Motor Co. have also begun retooling production lines at idled plants to make ventilators and other medical equipment needed to fight the pandemic.

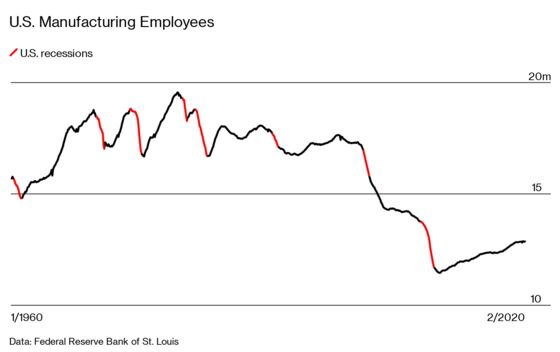

Yet much of the help coming from the federal government is still expected to take weeks to deploy. Also, the scale of the wartime manufacturing mobilization now taking place pales compared with everyday production. A recession now appears inevitable. And it is an historic fact that America’s recessions tend to be worse for manufacturing workers. Some 2.3 million of them lost their jobs in the last downturn. That’s roughly on par with the estimated 2.4 million job losses sustained by all sectors of the U.S. economy from 1999 to 2011 as a result of the “China Shock”—when that country became the so-called world’s factory—according to a group of economists led by MIT’s Daron Acemoglu and David Autor.

Economic downturns also have a habit of accelerating profound changes that lead to longer-term job losses. Past downturns have spurred investment in the automation of production lines, for example, says Mark Muro, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who’s written extensively on the role of technology in economic development. And this one isn’t expected to be different.

In one 2012 study economists found that since the 1980s, 88% of the “routine”—or easily automated—jobs lost in the U.S. disappeared within 12 months of a recession. Muro estimates there are now 36 million such vulnerable jobs in the U.S. “That’s one meta thing that will be a reality in the next year,” he says. “Managers are motivated by the cruel reality of the bottom line.”

What happens this time, of course, will depend largely on how long the near-total collapse in economic activity lasts. “Longer than I thought just a week ago” is the answer you hear most often from economists, company executives, and even workers on the production line.

In Waukesha, Wis., Austin Ramirez, chief executive officer of family-owned Husco International Inc., which makes hydraulic parts for major automakers, says during the last full week of March, his customers went from lodging orders to “telling us to just shut it all down.” He now expects an 80% to 90% drop in business in April. How does it compare to the last recession that came with the global financial crisis? “I think it’s going to be worse. And ’08 and ’09 were terrible for us,” he says.

Husco has so far avoided layoffs, and Ramirez hopes he can hold the line. About an hour’s drive due west, in Fitchburg, Wis., the Sub-Zero Group Inc., which makes high-end fridges and other residential kitchen appliances, notified the state last month that it was laying off approximately 1,000 workers for a two-week period.

The company’s original plan was to put everyone back to work on April 13. Yet as Wisconsin braces for a surge in Covid-19 cases and the state and federal government extend shelter-in-place orders and other restrictions on movement, it doesn’t take much imagination to see the date slipping into May or beyond. In its March 19 letter to state officials announcing the temporary closure, Sub-Zero ominously said it expected demand for its products “to remain down.” It also warned that “some employees are anticipated to not be recalled.”

“I hope this doesn’t last long, but I think expecting it to only last a month is not realistic,” says Aaron Richardson, the mayor of Fitchburg, a city of 29,000 that had been experiencing a boom thanks in part to its location just outside Madison, the bustling university town that’s also the state capital.

For many manufacturing companies, the Covid-19 shock has added a layer of uncertainty on top of preexisting conditions ranging from the impact of trade wars and tariffs to the woes of Boeing Co., which with 17,000 suppliers in the U.S. alone is a major economic engine for the country.

At Haynes International Inc., executives were already struggling with the impact of Boeing’s decision earlier this year to halt production of the 737 Max when the coronavirus crisis hit. The specialty metals Haynes’s plant in Kokomo, Ind., churns out are used in the fabrication of the plane’s fuselage as well as its jet engines, which are made by a joint venture involving General Electric Co.

Then in early March, when Covid-19 cases began ticking up in several U.S. communities, managers at the Kokomo plant began deep-disinfecting the premises daily and introduced staggered shifts so workers would be in less close contact. But with orders tumbling and concerns about employees’ well-being mounting, the company moved to shut things down.

The March 19 notice the company filed with state authorities called for a two-week shutdown affecting about 625 workers at the Kokomo facility and some 140 at its headquarters nearby. Dan Maudlin, the company’s chief financial officer, says the hope remains that business will bounce back quickly as the pandemic stabilizes. But executives are also resigned to the helplessness of their situation as they dial in for their team calls each day, he says. “It’s literally a daily changing environment,” Maudlin says. “We’ll just see what happens with the whole economy in general, and hopefully we’ll flatten the curve” of Covid-19 infections.

The unprecedented nature of what’s being described as an economic hard stop isn’t lost on many people. “This is the greatest social upheaval in America since the Great Depression or World War II, and we’re in uncharted waters and need to be flexible,” says Patrick Gallagher, a senior United Steelworkers official who represents hourly employees at a U.S. Steel facility in Lorain, Ohio, that is also scheduled to be shuttered in May.

The steel industry, which Trump hailed as one of the great successes of his protectionist policies, is again finding itself at the center of a downturn. ArcelorMittal SA has idled a blast furnace at its Indiana Harbor site and another at its Dofasco plant in Canada. Both supply critical parts to the automotive industry. U.S. Steel plans to shut down one of its blast furnaces in Granite City, Ill., which supplies both the automotive industry and the oil industry. Trump visited the Granite City mill in the summer of 2018 to mark the reopening of its two blast furnaces thanks, company executives said, to his tariffs.

The recession is also likely to hit communities such as Granite City and Lorain that have borne the brunt of America’s deindustrialization over the past four decades and had in many cases staged only a fragile recovery in recent years. “At the foreground is this absolute emergency for precarious service workers,” says Muro of Brookings. “But in a decade in which much of manufacturing country never really recovered fully, we are seeing another brutal event now.”

While much of the focus is on the spread of the virus in major cities such as New York, the longer-lasting economic turmoil—or at least the slower recovery—is likely to be in smaller cities that took years to bounce back from the last recession, says John Lettieri, who heads the Economic Innovation Group, a think tank that made its name focusing on the geography of America’s last downturn. In one such place—Fort Wayne, Ind.—the damage is already apparent. Demand at food pantries surged 40% once the economic shock started at the end of March, according to an umbrella group for the city’s religious congregations.

This downturn is also likely to hit midsize companies that are often stuck in the middle of supply chains and more vulnerable to even short shocks. Federal aid may help some of them weather it a bit. But even when their employees return to work, they will do so to a new normal of lower demand. “One of the great lessons of the Great Recession is that it takes a long time to rebuild,” Lettieri says. “These things are not overnight exercises.”

Dennis Slater, president of the Association of Equipment Manufacturers, which represents companies that make gear for the farming, oil, mining, and construction industries, says the mood among his 1,000-plus members has turned in recent days from seeing a short-term shock to recognizing something that will have a longer-lasting economic impact. “This is not going to be 30 days,” he says. “It’s not just about Covid-19. Even when we’re through that, there’s going to be this uncertainty: ‘Are we really through this, OK? Are we done? Can we go back to business again?’ I think that uncertainty will take longer than whatever it takes to get through this.”

Even as such questions build, there are those pushing for a rapid return to whatever approximation of normalcy is available. The U.S.’s Big Three automakers have been locked in a battle with their union, the United Auto Workers, over whether it’s even safe to resume production with the virus continuing to spread. Ford announced on March 31 it was canceling plans to restart some U.S. factories in mid-April and now says it doesn’t know when it will resume production.

Caught in the middle are frontline workers, some of whom were heartened by Trump’s push to lift most if not all recommended restrictions by Easter. (The president abruptly changed tack last weekend after being convinced by health officials that lives were still at risk.) One of them is Brian Pannebecker, a forklift operator at a Ford axle plant in Sterling Heights, Mich., who—even with union benefits that give him 85% of his non-overtime take-home pay—is taking a meaningful financial hit from the closures.

“I’m not coming in any closer contact with people at work than I would if I go up to Kroger and buy groceries for the week,” says Pannebecker, who is a Trump supporter. “Like President Trump has said, you can’t allow the cure to be worse than the sickness and let it destroy our country.”

“We’re going to have to learn to live with this. And there may be another wave of it coming down the road. So we’re going to have to learn to function and take certain precautions,” he says. “But we’re going to have to get back to work sooner or later. So let’s start looking towards how we’re going to do that instead of just sitting at home and twiddling our thumbs.”

Even for those still at work in American factories, the economic impact is rapidly creeping closer. As much of the rest of the U.S. late last month was coming to grips with the realities of home working and schooling, Daniel Logan, a supervisor at a plant in rural Manchester, Tenn., that turns out weatherproof mats and carpets for automakers including Mazda, Toyota, and Volkswagen, was counting his luck. Covid-19 cases were popping up in nearby counties, but the disease hadn’t yet reached Coffee County, where his employer, VIAM Manufacturing Inc., is located.

The luck is beginning to run out. The county reported its first confirmed case of Covid-19 last weekend. Logan says the 350-person factory where he works was running full steam until suddenly, on March 26, VIAM cut temporary workers in two of the three buildings. “Definitely not looking forward to the coming weeks and seeing what’s going to happen, because I don’t doubt one bit that our company will eventually have to close its doors,” says the 37-year-old father of three. “Everywhere is feeling the reach.”

Logan and his wife have loaded up on frozen food and have enough savings to get by if he gets laid off, he says. But he worries about co-workers he knows who are “week-to-week paycheck people” and will struggle to make it even until the $1,200 government checks promised in the rescue plan arrive. “It’s going to be a rough couple of weeks, for especially those people,” he says.

Read more: Germany Pays Workers to Stay Home to Avoid Mass Layoffs

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.