Two Texas Billionaires Think They Can Fix Philanthropy

Billionaires John and Laura Arnold’s full-time job is to give more and more of that fortune away.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Billionaires aren’t too popular right now. As inequality surges, even the most generous of them are coming under attack. Philanthropy is just one more way the superwealthy grab too much sway over society, critics say, and there’s little check on their vast power.

John and Laura Arnold agree with many of these critiques. They’re also billionaires, and their full-time job is to give more and more of that fortune away—not to art museums or orphans but toward the goal of changing government policy. According to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, the Arnolds are worth $2.5 billion, not including more than $2 billion held by their foundation.

Look at a controversial issue in the U.S., and there’s a growing chance the Arnolds are weighing in. They’re giving the pharmaceutical industry a run for its lobbying money by bankrolling a new group, Patients for Affordable Drugs. They also spent millions of dollars last year pushing successful anti-gerrymandering ballot measures in Colorado, Michigan, Missouri, and Utah. They’ve funded research into criminal justice that’s persuading legislators, judges, prosecutors, and law enforcement to revamp how they handle everything from policing to parole.

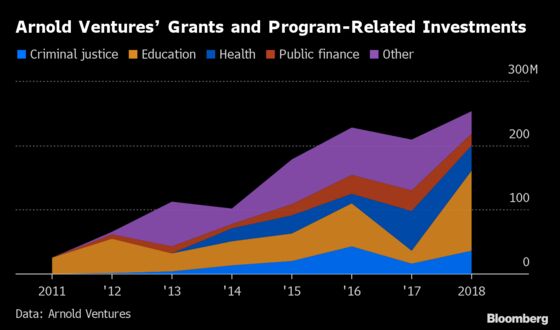

After the Arnolds reorganized their philanthropy into an LLC—a controversial move in itself because it lowers transparency requirements—their giving accelerated this year.

Since 2011 they’ve written checks for more than $1 billion—half of that since 2017. Last year the Arnolds committed $284 million in grants, a 28% rise from their commitments in 2017. This year their grantmaking is on track to jump an additional 33%. That doesn’t include tens of millions of dollars spent through their political giving arm, the Action Now Initiative, nor the skyrocketing cost of paying their more than 100 employees—a roster of highly credentialed experts, lobbyists, and communication pros that numbered a mere 14 people eight years ago.

John was a legendary trader until he abruptly quit and shut his hedge fund at age 38. His wife was also an overachiever, a lawyer at a firm that handled huge corporate mergers. Now in their mid-40s, they’re putting their distinctive stamp—bipartisan, fiscally conservative, and carefully researched—on policies at all levels of American government.

Over the past few decades, the surging wealth of the top 0.1% has spurred many promises of lavish donations. But the majority of pledged money sits unspent, as U.S. tax rules make it easy to procrastinate. Foundations need to pay out only 5% of their assets per year (less than typical market returns); money can sit indefinitely in a donor-advised fund, or DAF, which offers the same tax benefit as a foundation with far fewer rules. “People are getting a tax deduction today for giving that’s going to happen sometime—especially with DAFs—potentially much later in the future,” John says. “Is that really the spirit of the rules?”

DAFs are surging in popularity, with assets rising 20.1% in 2018 from the previous year, to $121.4 billion, according to the National Philanthropic Trust. Meanwhile, markets keep rising. Even the most philanthropic billionaires—such as Bill Gates and Warren Buffett— are richer now than they’ve ever been.

“They have the intent to do good,” Laura says of her ultrawealthy peers. “But in practice it just isn’t happening.” Foundations and DAFs should spend at least 7%, John has proposed, which could end this “hoarding of resources” and get billions of dollars more to charities.

The Arnolds are aware that, as two obscure billionaires exercising power, they’re likely to attract suspicion. “There are some legitimate questions as to whether somebody with vast amounts of resources should be in a position to influence policy,” Laura says. But they say their intentions are good. “The common thread is simple: We want to improve people’s lives.”

How do these billionaires decide the right way to do that? The Arnolds’ answer is unapologetically nerdy. They’re so dispassionately analytical, they’ve repeatedly dismissed the idea that even their background influences where they give. (She’s from Puerto Rico; he’s from Dallas.) Instead, they say, they look for “market imbalances”—lopsided power in politics or business that’s creating problems. As Laura puts it: “What is it that’s causing this dysfunction that’s yielding these suboptimal outcomes for society?”

The first step is often to fund a research study—“philanthropy as R&D,” she says. For example, in June, research the Arnolds funded found that violations of parole and probation, often occurring a decade or more after initial sentences were served, account for 45% of state-level imprisonments. Most are technical violations, such as a missed appointment, a failed drug test, or even a traffic stop.

Step two is using that data—and lobbying and political donations—to get Democrats and Republicans to hammer out a solution. The pair is arguably the largest funder of the U.S. criminal justice reform movement—which is lately racking up victories at the local, state, and federal level—and they’ve added battles with unions on pension reform to the tussles with the pharmaceutical industry.

They supported the First Step Act, a federal bipartisan criminal justice reform law passed a year ago, though they often find more success on the state and local level. On probation and parole, they’ve allied with the Reform Alliance, an advocacy group co-chaired by billionaire Michael Rubin and rapper Meek Mill.

The Arnolds’ spending on the 2018 midterms mostly favored Democrats, but they vow that their 2020 giving will be more even, following their own philosophy, which challenges both the Right and the Left. “We’re looking for centrists on either side of the aisle,” John says. (Michael Bloomberg, the founder and majority owner of Bloomberg LP, which owns Bloomberg Businessweek, was the largest giver to Democrats in 2018, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.)

John, 45, got fabulously rich playing the energy markets. As a trader at Enron, he led one of its biggest legitimate profit centers. When the company collapsed, he started his own hedge fund, Centaurus Advisors. His famous trades included a massive haul at the expense of Amaranth Advisors, a hedge fund that imploded after losing $6.6 billion in 2006.

Fifteen years ago, Laura—then Laura Muñoz—was a high-powered mergers-and-acquisitions lawyer in New York. A graduate of Harvard, Cambridge, and Yale Law School, she took a break from big M&A deals to work for an oil-exploration startup in Houston. Her real estate agent, who was friends with John’s mother, suggested the trader might show her around the city. She didn’t realize it was a blind date until later.

They married, had three kids, and signed the Giving Pledge in 2010, promising to donate “the vast majority” of their assets before they die. Laura, 46, ran the foundation until 2012, when John surprised the markets by shuttering Centaurus and joining her. They work in adjoining offices in Houston, arriving every day by 8:15 a.m. and staying for eight or nine hours of reading, meetings, and interviews.

It’s hard to detect much difference in their outlooks—especially their hyperintellectual approach to giving away money. “They got to where they are by making really hard decisions, but they didn’t make those decisions like cowboys,” says Kelli Rhee, president and chief executive officer of Arnold Ventures and the tiebreaking third vote on the foundation’s board. “They made them by doing the legwork.”

Their faith in cold hard data is obvious in their giving. The Arnolds have become a fire hose of funding for randomized controlled studies. On gun control, last year’s shooting in Parkland, Fla., prompted them to step in with $20 million to create the National Collaborative on Gun Violence Research, studying the problem as a public-health threat, an area of research Congress has refused to fund.

Laura is so obsessed with data—and the idea that so much existing research is unreliable —that she gave a TEDx Talk on the topic in 2017. Without good data, the Arnolds say, it’s impossible to know what the real problem is or what the best solution is. It’s obvious to them, for example, that the criminal justice system “promotes inequality and punishes people for being poor,” Laura says, while wasting billions of dollars a year—an issue “that actually speaks to both conservatives and liberals.”

Solving any of these problems isn’t easy. “I would encourage people to name a policy domain that knows less about itself than criminal justice,” says Jeremy Travis, a former president of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice who now leads Arnold Ventures’ work on the topic. This year it announced another $17 million in grants to study prisons in the U.S., which has the highest incarceration rate in the world.

“We’re about how can we get better results with less money,” John says. A new program or initiative will last only if it’s affordable. If not, he says, “then the next recession it’s just going to get cut.”

The idea behind running a philanthropy through an LLC rather than a foundation—most famously pioneered by Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, in 2015—is that it gives everyone inside the organization much more flexibility and also makes their activities harder for outsiders to track. Tax rules require nonprofits to steer clear of political activity, but in an LLC, a health-care expert who once stuck only to research grants can now strategize with advocacy groups and even talk policy with lawmakers.

LLCs “can basically operate as naked political voices without any transparency,” Stanford professor Rob Reich says, though he adds that the Arnolds seem otherwise to be “appropriately inviting the scrutiny of journalists and the public.”

There’s one limit to their boldness: They take great pains to avoid looking as if they’re taking one political party’s side. “We need to give the Trump administration credit,” Laura says, for work on issues such as criminal justice reform and drug pricing. They “have strong disagreements, as well,” John jumps in to add.

Centrists in a time of polarized politics, and nerdy technocrats in a populist era, the Arnolds aren’t sure what to do about the presidential race next year. “I would support the person who I thought had the best chance to unite this country,” John says. “Unfortunately, I’m not sure any of the candidates have a high probability.”

The group supports House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s bill, the “Lower Drug Costs Now Act of 2019,” which would let the federal government negotiate prices with drugmakers. The Congressional Budget Office estimates it would save Medicare $345 billion over the next decade.

Impact investing has become a $502 billion market globally.

Socially responsible investment funds hold about $9 trillion.

Arnold Ventures estimates $14 billion is spent every year jailing almost half a million people before they’re convicted of a crime. Many stay locked up because they can’t afford the cost of bail.

In 2014, Phoenix voters rejected an Arnold-supported ballot measure to replace pensions with a 401(k)-style retirement plan for new city employees.

One Arnold-funded study looked at 100 experiments published in top psychology journals and found only about 40% could be replicated.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Chris Rovzar at crovzar@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.