Everyone Has a Contact-Tracing App, and Nobody’s Happy About It

People from Singapore to San Francisco say they don’t want to use them, citing technical problems and skepticism.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Contact-tracing apps seemed like they might turn out to be technological saviors when they made their debut in March. The hope was that some semblance of normal life could return if people knew when they came into contact with someone carrying the novel coronavirus. Yet as the weeks go by, that’s not happening.

The apps, most of which work by using Bluetooth to connect phones to each other and ultimately let people know if they’ve been exposed to the virus, have instead raised hackles about privacy and surveillance. And there are worries about whether the technology is even effective.

People from Singapore to San Francisco say they don’t want to use them, citing technical problems and skepticism that privacy protections are for real. A system developed by Google and Apple Inc. isn’t being widely adopted because of limitations it imposes on governments using its technology. Instead, many countries have decided to come up with their own solutions, which are usually incompatible with apps used elsewhere, making them useless for travelers. And in India, Southeast Asia, and much of Africa, smartphone ownership is too low to reach the threshold for contact tracing to be effective, which is at least 60% of a population.

“Given the haphazard way many of these apps have been developed, there are obvious concerns about their efficacy and privacy implications,” says Samuel Woodhams, the digital rights researcher at internet research firm Top10VPN. Contact-tracing apps are meant to provide a technological solution for public-health officials, who in the normal course of trying to stem a contagious disease outbreak make phone calls and site visits to track down people who may have come into contact with a carrier. With millions of people infected with Covid-19, such methods are too slow. Developers saw an opportunity for smartphone apps to assist, but putting the technology into action hasn’t been easy.

When Singapore became the first country to roll out a voluntary Bluetooth-enabled app called TraceTogether in March, people were eager to try it. Almost 20% of the population rushed to download the app in the first 10 days, and the share is only about 25% now. People complained that TraceTogether drained their cellphone batteries and often required restarting. The technology also did nothing to stop a second wave of infections among Singapore’s migrant laborers, who come from countries such as Pakistan, Bangladesh, and India to work as construction workers and cleaners. Many don’t own a smartphone.

Now, prominent members of the tech community are calling on Singapore officials to integrate TraceTogether into a new app called SafeEntry, which records a person’s name and contact number. The system works like a digital check-in and is mandatory for anyone entering a business, including supermarkets and malls. The government has assured the public that the data will only be used for contact tracing and is exploring options such as a portable device for those who don’t have smartphones.

Most contact-tracing software works in a similar way. When two people with an app spend time together, their phones create a digital, anonymous record of that contact. If one person becomes infected, they can send a warning to everyone in close recent proximity while keeping their own identity a secret. The app can then suggest taking precautions, such as self-isolating, monitoring for symptoms, or taking a test.

But there’s been a heated debate over how the data are used and stored. In the Google-Apple system, called Exposure Notification, all of the information is kept on an individual’s phone and isn’t passed to a central database, which tech companies say helps protect privacy. Yet governments have complained that not having access to the data hurts their efforts to fight the spread. The U.K. has argued that its centralized system will help track outbreak patterns, do follow-up testing, and plan reopenings. It’s also promised to keep location data anonymous.

The Indian government’s mandatory order for citizens to download its own app, Aarogya Setu (meaning “health-care bridge” in Hindi), sparked anger about the intrusiveness and the use of GPS tracking. “India is the only democratic society in the world which is embracing the Chinese command-and-control approach to using technology to respond to the coronavirus without adequate protections for people’s fundamental rights,” says Sidharth Deb, a counsel at the New Delhi-based Internet Freedom Foundation.

Yet a majority of Indians don’t even have smartphones to be able to download the app. India had 500 million users in 2019, or a penetration level of 36%, according to Rajeev Nair, a Bengaluru-based senior analyst for Strategy Analytics. Downloads of Aarogya Setu reached just 100 million by mid-May, two weeks after its launch, even with the government mandate. While the app is aimed at India’s city dwellers, there’s a significant percentage of daily wage earners woven into the country’s urban fabric outside the professional workforce—drivers, fruit sellers, anyone with whom office workers with smartphones could come in contact. To try to bridge the technological gap, the government has rolled out a second version of the app for India’s cheaper JioPhones and is asking people without smartphones to answer a text survey. It rescinded the mandatory order after the backlash.

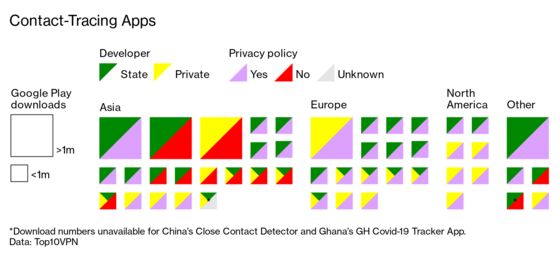

Of the 47 contact-tracing apps already in use in 28 countries as of mid-May, 23% of them had no privacy policy, 53% don’t disclose how long they plan to keep user data, and 60% had no publicly stated anonymity measures, Top10VPN’s Woodhams found. None has reached the 60% download level needed to be effective. An April white paper by the American Civil Liberties Union also said that most location-tracking methods used by apps are too inaccurate to be useful for automated tracking.

To be sure, there are benefits to contact-tracing apps, even if not everyone is using them. They can provide notification about infection risks and quarantine guidance faster than human tracers, according to a statement from researchers at the Big Data Institute at the University of Oxford. “Even at low levels of uptake, apps can reduce transmission and have a protective effect on the population and support people without smartphones,” says Dr. David Bonsall, a co-lead on Oxford’s app program and clinician at John Radcliffe Hospital.

Still, there’s a lot of skepticism for developers to overcome. A poll by Axios and Ipsos Group found 66% of respondents said they would reject an app developed by tech companies, and even more wouldn’t download one from the U.S. government. “The whole concept of American democracy is about local control and civil liberties,” Cliff Young, president of Ipsos U.S. Public Affairs, said in a statement with the poll results.

There’s a long way to go to make the apps effective enough to override the privacy concerns, technical issues, and current haphazard approaches around the globe. In the meantime, municipalities such as New York City plan to hire thousands of human contact tracers to do the work the old-fashioned way. Michael Bloomberg, founder and majority owner of Bloomberg LP, the parent company of Bloomberg Businessweek, is donating $10.5 million to that effort together with Bloomberg Philanthropies.

“Contact-tracing apps need to be reliable, transparent, anonymous, and voluntary,” says Woodhams. “Without this, they will remain in a counterproductive, self-perpetuating cycle that continually drives down the number of users and limits their effectiveness.” —With Gerrit De Vynck

Read more: The Software That’s Powering All the Coronavirus Dashboards

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.