Diversity at Elite Law Firms Is So Bad Clients Are Docking Fees

Diversity at Elite Law Firms Is So Bad Clients Are Docking Fees

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Elite law firms in the U.S. and the U.K., long seen as fusty bastions of mostly White men, are being pushed by some of their biggest customers to change. Facebook, HP, and Novartis are part of a growing number of major global companies that have warned they’ll take their work elsewhere or cut fees unless they see more racial and gender diversity in the law firms they hire.

It’s a serious threat: Facebook Inc. last year spent $1.6 billion on legal fees, settlements, and fines. “Money can make movements,” says Lauren Hauber, a Facebook legal operations manager in San Francisco. “And using buying power to push for change will oftentimes start to move the needle.”

It’s not that the companies pushing for change are models of diversity. Most have their own distinct struggles with representation. But corporate law firms have proved particularly slow to shape up, with many structured as partnerships that give relatively few dealmakers decades of influence over how a firm is run. That’s an increasing concern for clients, who say diverse legal teams deliver more creative and well-rounded advice.

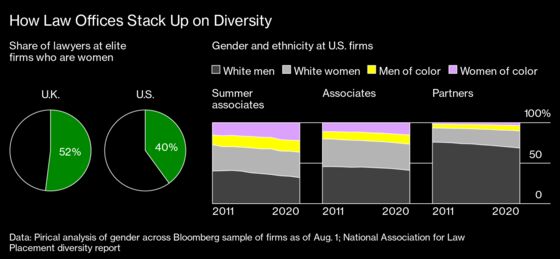

Although many law firms have made public commitments on racial, gender, and economic diversity, they’ve got a long way to go. Women make up a little more than a quarter of partners at 10 of the most prestigious firms on either side of the Atlantic, according to research by diversity-analytics company Pirical. About 10% of partners at U.S. firms are people of color, according to a 2020 survey of 883 law offices by the National Association for Law Placement. Racial minorities make up only 8% of U.K.-based partners at elite British firms, according to Bloomberg calculations based on company data. To put that in perspective, about 12% of directors at the U.K.’s 100 largest companies are from an ethnic minority, data from a government-commissioned report show.

“There are enough clients who are focused on this—passionate about it and see it as their responsibility to improve diversity across the legal sector—that it will definitely have an impact on balance sheets,” says Georgia Dawson, who last year became the first woman to be elected senior partner—a crucial management role—at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer. The 278-year-old firm is part of London’s so-called Magic Circle, a group of elite law offices that have dominated the U.K. legal sector for decades.

This year, Linklaters, another Magic Circle firm, picked its first female senior partner since its founding 183 years ago, and 132-year-old rival Slaughter & May chose a woman as managing partner, a newly created role, in September.

The movement was gaining momentum even before last summer’s Black Lives Matter protests turbocharged the push for diversity and representation; Dawson says her clients, mostly banks, began asking about diversity five to eight years ago. A big break came in 2019, when 170 companies—including Heineken NV’s U.S. unit and Etsy Inc.—sent an open letter to law firms criticizing their lack of diversity. That same year about 60 top lawyers at European corporations signed a separate commitment to increase diversity and inclusion across the legal sector. Signees to that pledge have since doubled and include Anglo American, BHP Group, Royal Dutch Shell, Unilever, Vodafone Group, and other deep-pocketed clients.

Participants recognized their responsibility to use “the power of our purse as clients to help encourage greater diversity,” says Richard Price, general counsel at mining company Anglo American Plc. “That isn’t so much about threatening the firms to take our business away from them. It’s really about working with them to encourage their initiatives to drive diversity.”

HP Inc. was one of the first companies to warn it would penalize law firms that flunked certain diversity benchmarks, saying in 2017 it would temporarily withhold a portion of fees from those that didn’t have someone diverse handling staffing issues, or at least one racially diverse attorney either managing or performing 10% of the work. The California-based company has on average enforced that threat on one or two firms each quarter since then, according to a spokesperson.

Others have followed suit. Facebook requires that half the lawyers on its external U.S. legal teams are diverse—in terms of race, gender, sexual orientation, or disability status—boosting the mandate from 33% earlier this year, and is considering a policy to withhold fees from law firms if they don’t meet targets, Hauber says. Swiss pharmaceutical giant Novartis AG has said it will withhold 15% of fees if firms don’t meet its diverse staffing commitment, and telecommunications provider BT Group Plc has promised a seat on its advisory panel to the law office with the best representation.

“If any law firm turns up on a matter with nothing but men working for us, they would have failed to meet one of our criteria,” says Rosemary Martin, general counsel at U.K.-based Vodafone Group Plc.

Such requirements are not without controversy. In January, Coca-Cola Co.’s top lawyer proposed a policy demanding that outside law firms include diverse attorneys on at least 30% of new business with the company and that Black lawyers receive at least half of the billable work. He left after eight months on the job, and his successor is reviewing the standard. The company declined to say whether this personnel change was related to the diversity push, and a spokesperson said in August that Coca-Cola remains “fully committed to advancing equity, diversity, and inclusion in the legal profession.” The policy spurred at least one group of shareholders to write to the board in opposition, saying it may give rise to lawsuits against the company.

A more diverse pipeline of young lawyers may help tackle representation in years to come, based on law school data and the number of women in lower levels. Below the rank of partner, 50% of the attorneys at top U.S. and U.K. law firms are women. That’s even higher in transactional practices such as mergers and acquisitions, where women account for 60% of nonpartner attorneys in the U.K. and 49% in the U.S.

Many top U.K. firms have trainee cohorts that are majority female, and they’re pushing to attract candidates from racial minorities, too. Almost 40% of summer associates at U.S. firms surveyed last year were people of color, a number four times higher than at the partner level.

Still, “we don’t want anyone to feel complacent about this,” says Jennifer Newstead, Facebook’s general counsel. “This is a journey that’s not finished.” —With Ruiqi Chen and Rebekah Mintzer

Read next: Why Australia’s Gender Inequality Problem Is Costing the Country Billions

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.