Big Dairy Is About to Flood America’s School Lunches With Milk

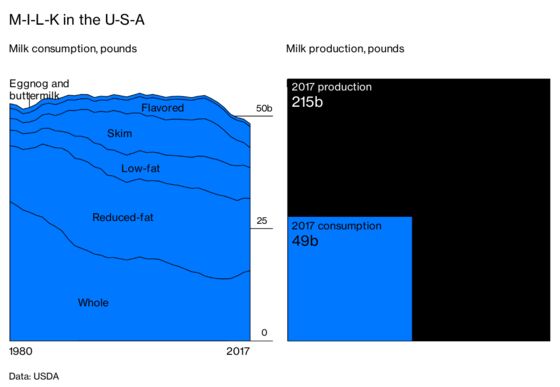

Per capita, people in the U.S. are drinking 40 percent less milk than in 1975.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Consider the lunch lady: long-suffering, warm-hearted. Or maybe fed-up and impatient. Always hair-netted. But how did she spend her summer? This past July, chances are she (lunch gentlemen are a rarer sight) was in Las Vegas for the annual conference of the School Nutrition Association. There, in the convention center at the Mandalay Bay hotel, thousands of cooks, cafeteria managers, and cashiers, toting swag bags in slow-moving waves, browsed a supermarket of brands—Tony’s pizza, Campbell’s soup, Cheez-It crackers.

Some purveyors splashed out for full-scale culinary demos, and it was during one of these, at 8:30 a.m., with an overhead camera broadcasting a gleaming cooktop onto a giant screen, that Food Network chef Jason Smith gushed about his favorite recipes from the dairy cooperative Land O’Lakes Inc. Smith, known for loud outfits such as the red shirt and black vest with tropical flowers he wore that morning, was a school cafeteria manager in Kentucky before he hit reality-TV stardom. In a homey drawl, he let the packed ballroom know he hadn’t forgotten how to stretch a school budget.

“Making your cheese sauce from scratch—you all know what that goes like,” he said, drawing laughs at the punch line: “You’ve got burnt cheese sauce.” Smith produced a bag of Land O’Lakes Ultimate White Cheese Sauce Blend and confided, “When you buy this, you don’t have to worry.” He snipped a corner of the bag and poured the contents into a bowl, then heated it up. A gooey sauce materialized. “Girl, get your head in that bowl, and lick ’er clean when it’s done!” he said, to whoops. The sales pitch was as thick as the sauce, and it kept on flowing. Over the course of an hour, Smith showed off a “cheesy cowboy meatball hoagie,” a Cuban mac-and-cheese sandwich, and a cheesy pizza salad. “If you’re not using them,” he said of Land O’Lakes’ “wonderful, wonderful” products, “you’re crazy.”

The American lunchroom war has taken another turn. Flaring first with the ketchup-as-a-vegetable controversy of the Reagan era, it’s raged anew since 2010, when the Obama administration backed the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act. The law directed the U.S. Department of Agriculture to rewrite the nutrition standards of the $13.6 billion National School Lunch Program for the first time in 15 years. The department soon required more fruits and vegetables, more whole grains, and lower sodium levels. Chocolate milk, if it was served, had to be fat-free. In many ways this was a frontal assault on dairy: Cheese, especially the American kind popular on burgers, is high in sodium. The new rules even told schools to make water available with every meal—after decades when the only beverage kids were routinely offered was milk.

A week after his appointment was confirmed in 2017, Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue, a stocky ex-Georgia governor who made his fortune in the grain business and was once a consultant to milk producers, sat down for lunch with grade schoolers in Leesburg, Va., to announce an easing of the restrictions. Higher-fat chocolate milk was back, along with more white breads and pizza. “I wouldn’t be as big as I am today without chocolate milk,” Perdue told the assembled reporters.

Menu revisions began rolling out within months, and the Agriculture Department finalized the rules in December. It’s a victory for many of the big food companies that count on schools as a steady source of revenue and see them as an opportunity to shape the buying habits of future consumers. The win is especially sweet for the $200 billion U.S. dairy industry, which has been in a self-declared crisis for years because of declining milk consumption.

The shift has particularly unwelcome consequences for the one-third of American kids considered overweight or obese. It underscores the contradiction at the heart of the meals program, which is simultaneously trying to feed schoolkids healthful food while supporting agribusinesses that want to pack the menu with their own products. And it shows the enduring power of diet in the cultural divide. In the months after the election of President Donald Trump, only one thing drew a direct rebuke from either Barack Obama or his wife, Michelle—the changes to her signature effort for healthful eating. As she put it soon after Perdue’s lunchtime visit: “Think about why someone is OK with your kids eating crap.”

But then, for many of the kids and the professionals serving them, the crap was the whole-grain pitas and skim milk the government forced on them. And it was ultimately the lunch ladies who got to decide.

“I have never had an outstanding successful athlete who was not a hard milk drinker,” the Green Bay Packers coach Vince Lombardi said in National Dairy Council ads in the 1960s, according to the 2018 book Milk! A 10,000-Year Food Fracas by Mark Kurlansky. For generations, milk was a dietary staple, the frothing glass your mother urged you to down with every meal. But consumption habits were changing even by the time the “Got Milk?” ads were winning awards in the 1990s. The Packers’ current star, Aaron Rodgers, let slip in 2016 that he shuns cow’s milk, causing a stir among home-state fans in Wisconsin, “America’s Dairyland.” (“I just wanted to get healthier,” the quarterback said of his mostly vegan diet.) Per capita, people in the U.S. are drinking 40 percent less milk than in 1975. Production, however, keeps rising. As a result, milk prices are sliding and dairy farmers are failing—Wisconsin alone lost 600 dairy farms in 2018.

Consumption is down in Canada and Western Europe as well, and it isn’t just a matter of taste. Among doctors, there’s growing recognition that high dairy intake can increase risks of heart disease, cancer, and weight gain. One widely publicized 2014 study by Swedish researchers, published in the BMJ, formerly the British Medical Journal, found that people who drank three glasses of milk a day—the amount of dairy suggested in U.S. dietary guidelines—had a higher risk of dying over 20 years than those who drank less than a glass. The authors speculated that this was because of inflammation caused by lactose, a type of sugar in milk. What’s more, the study found that the calcium in milk hadn’t made people less prone to bone fractures, contrary to popular belief.

The American Medical Association recommended in 2018 that the U.S. call meat and dairy optional in its next set of dietary guidelines. The AMA also asked that the school lunch program recognize something that’s become clear from genetic studies in recent years: It’s mainly people of Northern European descent who can easily process the lactose in milk. Among Asian Americans, intolerance to lactose is about as common as being right-handed, and it’s also prevalent among black people and people of Mexican heritage (one reason for a particularly weird twist that’s seen white supremacists turn milk into a symbol of racial purity in internet memes).

Even the architect of “Got Milk?” throws up his hands at the bind his old client is in. “The killer is white milk: It just doesn’t have a reason for being,” says Jeff Manning, who commissioned the ads for California milk processors and is now an independent marketing consultant. “I don’t think a millennial will ever drink a cold glass of milk.”

For the industry, that’s all the more reason to thank federally subsidized school meals. The “feeding programs” account for 7.6 percent of total fluid milk sales, by one producer’s 2017 estimate. The largest U.S. dairy processor, Dean Foods Co., ships 1.8 billion half-pints of TruMoo and DairyPure to schools a year. Two-thirds of sales in schools are flavored, according to the National Dairy Council. Counting what they drink everywhere, kids age 2 to 17 represent 40 percent of consumption, according to the Milk Processor Education Program, or MilkPEP, a quasi-governmental marketing group funded by federal levies on milk processors.

When the Obama-era rules took effect in 2012, requiring all flavored milk in schools to be skim, it only exacerbated the industrywide slide. Skim doesn’t taste as good, and more kids passed. By MilkPEP’s count, children caused the largest share of milk’s volume drop from 2011 to 2015. That rankled some in Congress, including Glenn Thompson, a Republican from Pennsylvania, a major dairy producer, who groused at a hearing in 2015, “I think a little bit of flavor goes a long ways.”

The federal government has had a hand in school meals since 1946, when military leaders convinced President Harry Truman of the need for healthier conscripts; the Agriculture Department now subsidizes 30 million lunches and 15 million breakfasts a day. Kids get as many as half their calories at school—a fact Michelle Obama emphasized when she made healthier school meals the centerpiece of her “Let’s Move” campaign for weight loss. Often, she argued, those calories were the wrong kind: Schools were letting kids load up on sugary drinks and low-quality carbohydrates.

The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act gave schools more money if they met updated nutrition standards. Under President Obama, these included leaner proteins, limits on calories, and a fruit or vegetable at every meal. The rules reached deep into the nonsubsidized foods sold a la carte or in vending machines, forcing junk-food companies to abide by the new sodium limits on snacks. Researchers at Harvard called the law “one of the most important national obesity-prevention policy achievements in recent decades” and estimated it would prevent 1.8 million cases of childhood obesity over 10 years.

Almost immediately, the rules came under attack. The potato lobby fought off limits the Agriculture Department sought to impose on “starchy vegetables”—for example, french fries. When another proposal would have reduced the amount of tomato sauce in pizzas that counted as a vegetable, it brought a fierce response from Democrats in Minnesota, including Senator Amy Klobuchar. Kevin Concannon, a former undersecretary who was then in charge of the school programs, remembers saying to a colleague, “I didn’t know Minnesota grew that many tomatoes.” No, he was told, opposition came from the Minnesota food giant Schwan’s Co., maker of frozen pizzas such as Tony’s and Red Baron.

Eventually, and crucially, Obama lost the lunch ladies. The School Nutrition Association, with 58,000 members, at first praised the law. But when it was implemented in 2012, kids were shocked by the smaller servings and blander menus. Some posted photos of unappetizing plates with the hashtag #ThanksMichelleObama. Those who could afford to began bringing their own lunches. That hit the budgets of the schools’ lunchrooms, which typically fund themselves using a mixture of the federal subsidy of as much as $3.31 a plate and sales of snacks and a la carte foods.

In 2013 the SNA began pushing Congress to water down the requirements. This break with the Obama administration caused a rift in the group—19 past presidents signed a protest letter—but it succeeded in adding a waiver to a budget bill that gave schools the option of serving more refined grains. Despite the changes, 2 million students had dropped out of the program by this past fall. Until Perdue stepped in, even more drastic changes had been coming. A lunch consisting of a turkey and cheese wrap with mustard, plus green beans, milk, and oranges on the side, would already have barely passed the limits for sodium. In another five years, the sodium caps would have been cut almost in half—an outcome painted as a kind of cheese apocalypse by Barry Sackin, a former vice president for public policy for SNA who’s now a consultant to food companies. “Can you imagine,” he says, “not being able to serve a cheeseburger or a grilled cheese sandwich or macaroni and cheese?”

The tenseness of the SNA’s recent history perhaps explains why it imposed a militant media-minding policy at its Las Vegas conference. Attendance at any speech and interviews with any SNA member had to be cleared with the group’s spokespeople. They also sat in on every interview and allowed only supervised strolls through the convention floor.

The association gets a majority of its funding from food companies and other vendors, which sponsor its biggest moneymaker, the annual conference. Last year, Domino’s Pizza, General Mills, PepsiCo, and Land O’Lakes were among the conference’s biggest sponsors, each contributing as much as $24,999. Companies also paid to host sessions at which they could directly pitch school food officials. A “culinary demo” such as Smith’s Land O’Lakes cheese-o-rama cost $3,500.

Kellogg Co. and the National Dairy Council teamed up to present Nutrition Smackdown!, billed as a kind of ammunition-gathering session for lunch ladies to contend with griping parents. It was led by Dave Grotto, an executive for Kellogg, the cereal maker in Battle Creek, Mich., and Jim Painter, a volunteer adjunct professor at the University of Texas School of Public Health in Brownsville. Painter told the crowd he’d try to talk them through one of their common frustrations: “moms that have it their goal in life to get rid of chocolate milk in your school.” The teaspoon and a half of added sugar in the typical half-pint carton of chocolate milk, Painter said, is worth it for the calcium it contains. He asked people to imagine a 16-year-old girl: “If she doesn’t get enough by the time she turns 30, her bones start turning to dust.” Of course, as the Swedish study demonstrated, that’s debatable—and calcium is also found in beans, oranges, and leafy greens.

Painter’s résumé runs to more than 50 pages and includes dozens of examples of talks and papers funded by various industry groups. In 2005, after the release of the film Super Size Me, he dispatched students to eat in fast-food restaurants for 30 days and produced his own documentary arguing that it’s possible to stay healthy by controlling portion sizes. He’s also been a member of the National Dairy Council’s health and wellness advisory panel and got an honorarium from the council for his SNA appearance. (A slide shown to attendees mentioned the honorarium, and Painter says he’s always careful to disclose any financial ties.)

The dairy industry, although diminished in recent years, still has immense resources. The industry sponsors an ice cream social for congressional staff every summer, and a welter of trade groups spends hundreds of millions of dollars annually promoting its agenda.

The National Dairy Council is the research and communications arm of Dairy Management Inc., a group in Rosemont, Ill., funded by levies on milk production and overseen by the Agriculture Department. It regularly brokers paid opportunities for university researchers to deliver speeches and write papers, according to emails of conversations obtained by Bloomberg Businessweek in public records requests. (A three-minute, prewritten talk on the “product benefits” of Rockin’ Refuel chocolate milk, for instance, was offered for $500.)

The outreach has helped fuel some of the industry’s splashier campaigns. Until 2007 ads touted drinking milk as a way to lose weight, based on studies funded by the dairy industry. The campaign was curtailed after the Federal Trade Commission said the Agriculture Department had determined there wasn’t enough evidence to support the claim.

Perhaps the industry’s greatest recent success is in carving out a role for chocolate milk as a sports beverage. In frequent rotation are the “Built With Chocolate Milk” ads featuring soccer players, Olympic athletes, and Golden State Warriors basketball star Klay Thompson. The spots claim chocolate milk is better than sports drinks at replenishing stores of glycogen after exercise—a claim that traces its roots to the work of Indiana University kinesiology professor Joel Stager.

In 2002, Stager was coaching swimmers at Bloomington High School South, and it wasn’t going well. The swimmers were often exhausted at practice, and they were losing weight. He learned a lot of them were skipping lunch. When one showed him an expensive protein drink and suggested they try it, Stager looked at the ingredients and found them to be familiar: The blend of protein and carbohydrates reminded him of chocolate milk. He asked parents to bring in gallons of chocolate milk, and the swimmers improved (and put on weight). He decided to run a test in the lab with cyclists, getting $5,000 in funding in 2003 from an Indiana dairy trade group and, later, $88,572 from the National Dairy Council. After the results were published in 2006, Sports Illustrated and a host of health magazines blared the counterintuitive findings: Chocolate milk is the drink of champions! Ads from MilkPEP followed.

Stager’s subjects, though, were athletes training four to six hours a day—the rare kids who weren’t getting enough calories. Now, having watched the study’s wide impact on popular culture, he says, he’s had misgivings. Several years ago he proposed another paper to the National Dairy Council, to examine chocolate milk’s effects on sedentary students. The council turned him down. “They weren’t willing to take the risk: What if they found out all the kids increased 15 pounds?” he says. “I would still like to do that study.”

For the chocolate-milk-hating moms of America, there were signs that the Obama regulations were working. Despite the decline in participation, schools reported that kids had started taking more vegetables. One study of 1.7 million meals in an urban Washington school district found that the meals’ overall nutritional quality had increased 29 percent. The Agriculture Department said 85 percent of schools hadn’t asked for the whole-grain waiver (though, according to SNA, that’s partly because the waiver is so complicated to get).

In some states, bitterness over federal meddling lingered, and so did the financial fallout for lunchrooms. “We followed those regulations to a T and lost a significant amount of business,” says Teresa Brown, child nutrition director for St. Charles Parish Public Schools, 25 miles west of New Orleans. Whole-grain biscuits, for instance, flopped; about 500 of 4,500 kids stopped eating school breakfasts.

Other districts balked at the extensive documentation demanded of schools. Joe Otranto, who’s managed school meal programs in North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, says he counted 72 new requirements, not all of them funded. When he tried putting hamburgers on a whole-grain pita at a high school in York, Pa., he sold 15 a day instead of 300.

Congressional critics from dairy-producing states also kept up the pressure, and they, and the industry, found a receptive ear in Perdue. He grew up on a dairy farm in Georgia, and he’s made a point of frequently visiting farmers. Only recently he was in the milk business himself. Among the brands pitched by Perdue Partners LLC, a consulting company he started soon after leaving the Georgia statehouse in 2011, was Sophia’s American Milk, which sold nonrefrigerated ultra-high-temperature pasteurization, or UHT, milk, in numerous flavors, to China.

Perdue essentially adopted the SNA’s recommendations. The new rules cut the Obama-era whole-grain targets in half. They also called off the big reduction in sodium that could have sparked the cheese apocalypse. Instead, a smaller cut is planned to start in the 2024-25 school year, potentially the end of President Trump’s second term.

The American Heart Association was among several groups of doctors to publish letters opposing the changes. And the Center for Science in the Public Interest recently measured them in terms likely to resonate with Trump, famed for his love of fast food. By 2022, the organization says, the difference in sodium consumption for high schoolers will be the equivalent of almost two Big Macs a week. —With Shruti Singh

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Ferrara at dferrara5@bloomberg.net, Jeremy Keehn

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.