Biden Will Need to Repair a Global Economic Order Trump Damaged

Biden Will Need to Repair a Global Economic Order Trump Damaged

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- If Donald Trump has illustrated anything as president, it’s that the postwar global economic order is more fragile than anyone thought. Think of America’s trading relationships and rank in the world as a painstakingly assembled collection of delicate pottery that for generations has been a source of civic pride and envy from the neighbors. Trump and his deputies have been the raucous gang of teenagers barging their way through, leaving a trail of chipped and smashed artifacts. President-elect Joe Biden is the genial grandfather leading a new team brought in to mend what they can. The questions now are: How much will they save? And how creative will they get in the reconstruction?

The good news for a global economy straining under the weight of a resurgent pandemic is that Trump and his band haven’t destroyed the liberal order, as many feared. They’ve left it battered. Perhaps they’ve even prepared its defenses better for another economic assault from China. But anyone thinking that Biden is simply planning to rebuild the U.S.-led order the way it was might be in for a surprise.

Trump’s biggest legacy for many of those who run the global economy and invest in it will be late-night stress dreams about his chaotic policymaking. Yet Trump and economic generals such as U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer have also scrambled the American politics of trade, opened the door to a new suite of tactics and tariffs, and brought to the fore what in many cases have been long-standing and bipartisan U.S. grievances. When Biden speaks of the need to “build back better,” he might be talking about the global economic order as well. It’s something he and his advisers have mulled for years.

“The system’s resilience should not be the end to a comforting story; it should be the starting point of a badly needed effort to reinforce and update the international order and address the real threats to its long-term viability,” Jake Sullivan, one of Biden’s closest policy advisers, wrote in a 2018 Foreign Affairs article titled “The World After Trump.”

The words “trade” and “economic order” don’t feature once in an economic recovery paper posted by the Biden transition team. Instead, the document echoes Trump’s promise to restore U.S. industrial might. It vows to “mobilize American manufacturing and innovation to ensure that the future is made in America.” It also stresses “the importance of bringing home critical supply chains” and pledges to “build a strong industrial base.” That fits with what advisers say is Biden’s plan to focus on making sure the U.S. approaches its relationships with everyone from China to allies in Europe from a position of domestic economic strength.

Rather than relying on new defensive trade barriers as Trump has, Biden’s plans hinge on encouraging investment at home via tax incentives for companies to build factories in the U.S., and government spending on infrastructure and alternative energy to boost demand. The underlying idea is that a stronger, more confident U.S.—rather than a belligerent one—can turn around the narrative that it’s a declining superpower, according to multiple advisers who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

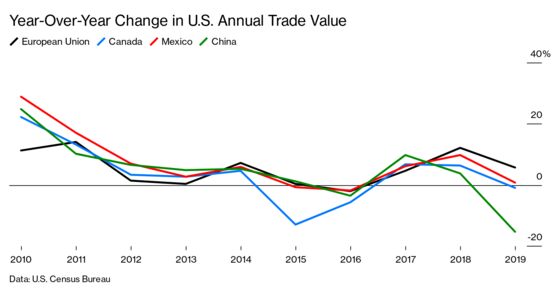

Any rebuilding of the global order is likely to begin with a methodical assessment of where things stand, which will take time and require a certain amount of patience from allies. Biden and Vice President-elect Kamala Harris have described Trump’s trade wars as disastrous, and yet they also refused throughout their campaign to pledge to remove the tariffs on imports ranging from Chinese components to French wine. Advisers say Biden intends to carefully review the tariffs. While he and his team are eager to portray themselves as getting to work quickly, they face the plodding reality of American political transitions.

Lighthizer’s replacement as U.S. trade chief is yet to be named, and Biden’s pick will face a Senate confirmation process that could take months. That’s likely to put on hold any major trade policy decisions until well beyond Biden’s first 100 days in office, a period that will be consumed by addressing the pandemic and trying to get a new stimulus package through a Congress that may be bitterly divided.

Top of the list on trade is what to do with China. The president-elect is facing decisions on whether to retain or lift tariffs and national security-driven bans on companies such as Chinese-owned Huawei Technologies Co., as well as whether he wants to build on Trump’s “phase-one” deal with Beijing. How to deal with China is set to color almost everything—including whether to go down the seemingly unlikely path of rejoining the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which doesn’t include China. The TPP has long been seen by strategic thinkers in Washington as a way to strengthen the U.S. position in the Asia-Pacific and to help counter China’s economic rise. Trump abandoned the pact on his first full workday in office. Many Asian allies would love for the U.S. to come back. “Going forward, we’re going to be looking more and more through the lens of China as we pursue trade policy,” says Wendy Cutler, who was the TPP’s chief U.S. negotiator and now leads the Asia Society Policy Institute. “When we choose negotiating partners, when we choose issues that we want to focus on, when we think of restrictions, it is all going to be through the lens of China.”

For Biden, another inescapable Trump administration legacy related to China is likely to be the scrubbing of the once-sacrosanct line between economic and national security. Trump has regularly invoked national security, sometimes dubiously, in his trade and technology battles, including in his assaults on Huawei and other Chinese companies. “The erasure of the line between economic and national security, to me, is here to stay,” says Jennifer Hillman, a former U.S. trade official who’s now at the Council on Foreign Relations and was a policy adviser to the Biden campaign.

The incoming administration also must address a brewing trade war with Europe related to a long-standing dispute between Airbus SE and Boeing Co. over industrial subsidies, and plans by France and other countries for new digital-service taxes aimed at American tech giants such as Alphabet Inc.’s Google and Facebook Inc. The situation won’t be helped by the European Union’s decision to go ahead with its own tariffs on imports from the U.S., authorized by the World Trade Organization. Attention will also turn toward negotiations with countries such as Kenya and a post-Brexit U.K., though none of those appear close to a conclusion.

A slow transition will add further delays to the stalled process of finding a new director-general for the WTO, where the U.S. has blocked the installation of Nigeria’s Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, who has the support of most other major members. Advisers to Biden say his administration will want at the very least to carefully review Okonjo-Iweala’s record, as well as that of South Korea’s Yoo Myung-Hee, the Trump administration’s preferred candidate.

Hanging over all this is the question of how much room the president-elect will have to maneuver given Trump’s rewriting of the politics of trade. The answer: quite a lot more than you might initially think, thanks to Trump.

His use of executive authorities contained in long-dormant statutes to impose tariffs ignored a time-honored deference to Congress on trade. It’s something that Biden might choose to do, too. The Section 301 investigation under the 1974 Trade Act that Trump used to launch his China tariffs was based on intellectual property theft. A Biden administration, one adviser says, might consider using the same strategy to deal with Chinese environmental or labor practices. Some Biden backers and former trade negotiators relish the leverage the president has created with his tariffs. Trump has strengthened America’s negotiating hand regardless of who’s in power, they point out.

Trump and Lighthizer have also shown what’s possible on Capitol Hill by prying at least parts of the Republican Party away from free-trade orthodoxy. Phil Levy, a former economic adviser to President George W. Bush who advised Senator Marco Rubio during the 2016 presidential campaign, points out that the Florida Republican has since embraced a new economic populism alongside other young Republican senators with presidential ambitions, such as Missouri’s Josh Hawley.

For decades, Republicans carried trade agreements over the finish line allied with only a small number of moderate Democrats—alienating those in the Democratic Party who felt trade deals left too many U.S. workers behind. “I think it’s important for the trading system that we end up reestablishing a solid majority for the kinds of things we’re doing. And that we not keep operating right on the fringe,” Lighthizer said in 2017 as he set about renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement. In the process of hammering out an updated trade deal with Canada and Mexico, Lighthizer won influential Democratic allies ranging from House Speaker Nancy Pelosi to Senators Sherrod Brown of Ohio and Ron Wyden of Oregon, the top Democrat on the Senate Finance Committee. He also won over a decidedly pro-Biden labor movement.

Of course, the bitter divisions in the U.S. mean nothing in politics will be easy for Biden, particularly if Democrats lose two Senate runoffs in Georgia in January and don’t win control of the body. There’s also still likely to be some reversion to the mean on trade among Republicans. Clete Willems, a partner at Akin Gump who served as deputy director of the National Economic Council under Trump, says the choice isn’t between a pro-trade, pre-Trump Republican Party and one of “America First” purists. “I hope we can take some of the best of Trumpism and combine it with the best of the old world to develop a trade policy that’s hard-edged, but at its core doesn’t see tariffs as the ultimate goal,” he says.

There are those who also see a lesson relearned on the pitfalls of protectionism. Douglas Irwin, a Dartmouth College historian of U.S. trade policy, argues that future administrations including Biden’s are likely to pause before using tariffs again in the way Trump has. “We had an experiment for four years about what it’s like to use tariffs for all sorts of objectives, and I don’t think it’s going to be viewed as a success,” Irwin says.

And yet, Trump has injected other, bigger existential questions into the system. One of his enduring legacies will be the “wake-up call for the rest of the world about this notion of American leadership and reliability” that he forced them to confront, says Chad Bown, a former member of Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers who’s now at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. That’s left broad uncertainty about the durability of America’s economic relationships, he argues, that will continue shaping business and trade with China and across the Atlantic. The uncertainty will remain even if Biden in the months ahead makes the unlikely choice to remove all of Trump’s tariffs. Add to that a pandemic that’s caused many countries to look inward, and the task of the friendly grandfather sent in to clean up the mess only grows. The global economy’s one-time order, it turns out, needs more than just physical repairs.

Read next: The Five Things Biden Must Do to Repair the Harm Trump Has Done

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.