Betterment’s Low-Fee Evangelist Has a Retirement Algorithm for You

Betterment’s Low-Fee Evangelist Has a Retirement Algorithm for You

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In August, Fidelity Investments, the wealth management giant, did something wild, at least by the standards of the wealth management industry. It announced it would offer two mutual funds with no management fees. The move was seen as the culmination of a price war among companies such as Fidelity, Vanguard Group, BlackRock, and Charles Schwab, and as great news for middle-class investors. Jon Stein, however, wasn’t a fan.

Stein is the chief executive officer of Betterment LLC, the startup that helped spark the fee war by persuading millennials to buy the cheapest funds they could find. “I love that fees are falling rapidly,” Stein says, before noting “problems” with Fidelity’s approach. The only way Fidelity can make money on a free product, he says, is if it persuades customers to also sign up for revenue-generating services, such as actively managed funds with significant fees. “They’re trying to cross-sell you into high-margin products,” he adds. “That’s the way most incumbents play the game. They typically try to hide fees or do a little bit of a bait and switch. And that’s not our model.” (A Fidelity spokesman says its pricing is transparent and that the free funds are standalone products.)

If Stein, 39, sounds cynical, that’s what the 2008 financial crisis did to people who were affected by it. The low-fee evangelist founded Betterment after a stint at First Manhattan Consulting Group before the recession. At one point he asked a senior partner why financial-services companies didn’t spend more time talking to customers. The partner’s response, Stein says, was that the banking industry doesn’t make money from customers. “We make money off money,” the partner told him.

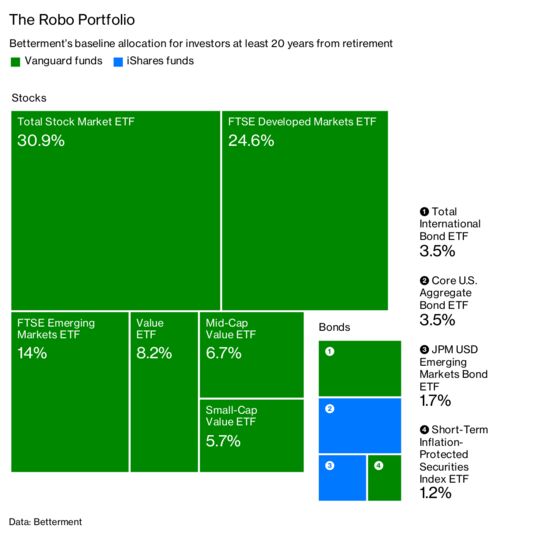

The premise of Betterment—which you know already if you listen to podcasts or spend time on social media, where the company buys lots of ads—is to replace the traditional financial adviser with an algorithm. When prospective investors go to Betterment’s website or app, they’re prompted to import information from their bank and retirement accounts and answer questions about their goals. The software then selects a handful of ultralow-cost exchange-traded funds, or ETFs, which are like mutual funds that trade on stock exchanges. And that’s pretty much it. The idea is to make things so simple, you might set up your account, arrange for direct deposits, and then never log in to it again until you retire.

As far as financial regulators are concerned, Betterment is legally indistinguishable from a human investment adviser, with the same fiduciary duties. But whereas normal investment advisers charge about 1 percent a year, Betterment’s fees are 0.25 percent, meaning that for every $10,000 you have invested, Betterment gets $25 annually. The difference between 1 percent and 0.25 percent may seem small, but it can add up to hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost savings over a career.

Since it started in 2010, the company has attracted about 400,000 customers, all in the U.S., who have an average of $40,000 in their Betterment account. It manages $15 billion in assets, up from $6 billion at the end of 2016.

This growth was probably inevitable. Software has been taking jobs in other white-collar service industries—bookkeepers, travel agents, tax preparers, Major League Baseball scouts, investment bank rainmakers—but Stein’s notion of a “robo-adviser” was initially dismissed by most of the financial-services industry. The term was originally used by Betterment’s critics in an echo of “robocall.” “It was 100 percent derogatory,” Stein says in an interview at the company’s headquarters in New York’s Flatiron district. “But pretty quickly we embraced it.”

The robo category now oversees more than $200 billion. Schwab and Vanguard offer robo services, and Goldman Sachs is said to be plotting one. The trend is so hot that earlier this year, Overstock.com Inc., a retailer better known for selling discount bedding, announced that it, too, would offer a robo-adviser.

Stein has raised $275 million from venture capitalists, but he also has a half-dozen VC-backed competitors, including Palo Alto-based Wealthfront Inc., which has raised more than $200 million and manages about $12 billion. “You’re seeing worlds collide where all these companies are recognizing that consumer preferences are changing,” says Devin Ryan, an analyst with JMP Securities LLC.

In a report published earlier this year, Ryan observed that millennials, who are beginning to inherit money from their baby boomer parents, offer wealth management startups a chance to steal market share from the old guard. “There’s going to be a record amount of money up for grabs,” Ryan says. That presents an opportunity for Stein, but also a challenge. After inventing a category, he’s now faced with competition from the most powerful players in finance. Stein’s plan is to get really big, really fast, and inevitably to put some of those big companies out of business. “Most of the financial-services industry is a complete waste of human time,” he says.

Stein grew up far from the world of finance, in suburban Dallas. He went to Harvard, where he studied behavioral economics. After college, “I thought I’d really like to do something to help people make better decisions,” he says. “But there was no one recruiting for that.” Stein did what everyone else at Harvard with a little bit of idealism and a desire to avoid poverty seemed to be doing: He went to Wall Street.

In 2003 he took a job as a consultant at First Manhattan. The work involved helping big banks improve their marketing strategies, which he found “a little bit gross.” “There’s a lot of smart, well-meaning people” in financial services, he says. “But a lot of the industry makes things intentionally hard or confusing or complicated for people.” Banks often talked a big game about customer service and then steered clients into loans they didn’t need, brokerage accounts that performed worse than index funds, and all manner of fee-producing vehicles, he says. (First Manhattan declined to comment.)

If Stein was horrified by Wall Street, he also found the industry thrilling in its amorality. The amount of money at stake was almost unfathomable—Fidelity, for instance, has nearly $7 trillion under management—despite the companies treating most consumers, in Stein’s opinion, poorly. “I felt like a fox in a henhouse,” he says. Stein already had an outline for Betterment in his head when he quit First Manhattan in 2007. He enrolled in Columbia Business School and in his spare time started teaching himself to code. Stein was convinced that the same technologies that had upended media were about to hit Wall Street.

Silicon Valley venture capitalists were coming to the same realization. The most successful of the startups created around this time, Mint.com, allowed users to import information from credit card accounts and offered suggestions for lower-interest alternatives. It occurred to Stein that Mint’s use of software to make personal finance recommendations could be adapted to tell people where to put their retirement savings—an enormous pool of money that was still managed by human financial advisers who were expensive and sometimes gave poor advice.

At the same time, passive investing was becoming more popular. The strategy, especially appealing in the wake of a crisis caused by Wall Street overreach, gives up on the idea of generating returns that beat the market. Instead, it focuses on matching market performance by buying the same stocks that make up indexes such as the S&P 500. Because this strategy requires a software program and not much else, the management fees these funds charge are minuscule. The growing popularity of index funds also helped fuel demand for ETFs.

Stein’s idea was to create an app that would automatically buy and sell ETFs for investors. He unveiled the company in 2010 at TechCrunch Disrupt, a startup competition in New York. Then, as now, Betterment promised radical simplicity. The first thing customers who logged in to the service saw was a picture of a dial with the words “stock market” on one side and “treasury bonds” on the other. They were then asked to move the dial to indicate their relative appetite for risk.

Stein made the finals of the New York competition, but lost to an Israeli antivirus company. The judges thought his idea seemed unserious—more like an investing tutorial for high school students than a money management service for grown-ups. “This starts to feel a little like a toy,” one of the judges complained. “It’s not a toy,” Stein shot back.

Even so, press from the competition gave Betterment a start. The company attracted 500 customers in its first week, a figure that climbed steadily as Stein pitched the service at conferences and began talking it up to personal finance bloggers. He worked in a one-room office with his co-founder, securities lawyer Eli Broverman, and two employees. Stein remembers one day toward the end of the summer of 2010 when he checked Betterment’s stats and realized, to his amazement, that he had at least five customers in each state. Later that year, Stein raised $3 million in a venture capital investment round led by Bessemer Venture Partners.

Betterment’s growth was slow compared with that of startups such as LendingClub and Prosper Marketplace Inc., which were raising tens of millions of dollars in venture capital at the time by making it easy to apply for personal loans on the internet. “It’s easy to give away money,” Stein says. “It’s much harder to take people’s money and say, ‘Invest with us, and we’ll give you a benefit in 30 years.’ ”

The great thing about customers who accept that deal is that they tend to be committed. Sixty percent of Betterment’s customers, Stein says, use automated deposits, meaning the fees are likely to continue to flow.

This explains why Stein’s idea attracted copycats. In October 2010, Silicon Valley startup KaChing, which had been founded as a social investing app where individuals could bet on portfolios run by amateur traders, changed tack. The company renamed itself Wealthfront and started recommending only managers who followed conventional strategies. At the end of the following year, shortly after Betterment signed up its 10,000th customer, Wealthfront launched its own robo service. At the time, the two companies weren’t competing directly because Wealthfront, unlike Betterment, required a $5,000 minimum investment.

In 2015, Wealthfront made a direct play for Stein’s customer base. It lowered its account minimum to $500 and gave its services away for free to anyone with less than $10,000 to invest. Betterment was charging a $3 monthly fee, which it waived if customers set their bank account to invest $100 each month. “It’s really disappointing that Betterment has decided to build their business preying on those who can least afford it,” Adam Nash, then CEO of Wealthfront, said in a blog post. In 2017, Betterment removed the monthly charge.

The two companies offered services that were nearly identical until February, when Wealthfront introduced a higher-fee fund that uses a popular hedge fund strategy known as risk parity. (The technique was popularized by Bridgewater Associates founder Ray Dalio. It’s complicated.) Wealthfront put a portion of customers’ savings in the new fund, charging them fees of 0.5 percent, or about five times the cost of a typical passive fund, on top of the 0.25 percent management fee. The move prompted an outcry from customers, who complained it should have asked for express permission. Wealthfront apologized, cut the price of the risk-parity fund in half, and let customers opt out more easily. “We’re proud of our approach to delivering investment strategies that are academically proven and time-tested,” a Wealthfront spokeswoman says.

Stein sees the mini-controversy as a case study in what makes Betterment different. “I would never do that,” he says. “We’re not chasing fads.” He adds that Betterment has no plans to add cryptocurrency trading or lending, two other popular ways some financial-services startups, including Silicon Valley-based Robinhood, have tried to attract customers.

The choice not to branch out beyond its core offering could limit Betterment’s growth. While $15 billion under management might sound like a lot of money, Betterment’s cut of that, assuming a 0.25 percent fee, would be only $37 million, not much for a company with more than 240 employees.

Rather than pile on additional services, Stein is focusing on increasing his existing business. His plan begins with traditional financial advisers, who can sign up to use its algorithms to buy and sell ETFs on behalf of their clients. Betterment still gets its 0.25 percent fee; the advisers can charge whatever they want on top of that to provide advice. He’s also going after the 401(k) account management business, a $5 trillion market in the U.S. Some 400 companies—mostly other startups, such as the online mattress company Casper—have signed up. Each pays from $4 to $6 a month per employee for the account—a low fee by industry standards—on top of Betterment’s standard 0.25 percent fee.

Adoption of the 401(k) product by companies other than tech startups has been slow, in part because human resources managers rather than individual employees have to be sold on the idea of dumping their old 401(k) provider. But Stein says it’s worth it: Most Americans have most of their savings in 401(k)s, which means Betterment has to be there if it hopes to outlast the competitors. “In some ways our vision is not as unique as it was eight years ago,” Stein concedes. But, he adds, most investors are still paying too much in fees for products they don’t truly need. “Without our leadership, the industry is going to slip back into the same problems as before,” he says.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net, Bret Begun

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.