Lebanon’s Deepening Economic Crisis Laid Bare by Beirut Blast

Lebanon’s Deepening Economic Crisis Laid Bare by Beirut Blast

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When Dany Chakour reopens his four upscale Em Sherif restaurants after repairing the damage wrought by the devastating Aug. 4 blast in Beirut, he plans to turn over the 11% sales tax he collects on each transaction to the local charities that helped clean up the city—instead of giving it to the government. “It’s a form of civil disobedience to give to trusted organizations in this time of need rather than to the state, where I don’t know how it will be spent,” Chakour says. “What has the state ever done for us? The state can’t even provide us with electricity.”

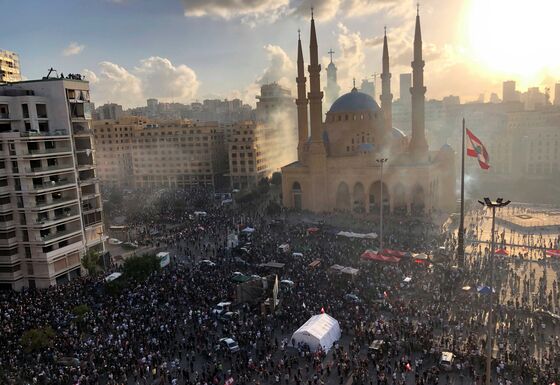

Lebanon was already coming apart at the seams before a 2,750-ton cache of ammonium nitrate detonated at the Port of Beirut, killing at least 171 people and wounding thousands. As the realization sank in that the blast was neither a terrorist attack nor the start of a new war with Israel but the culmination of decades of corruption and mismanagement, the streets exploded with rage.

Protests promptly dispatched the 7-month-old government of Prime Minister Hassan Diab, who blamed his failure to prevent the disaster or lift the country out of a deepening financial crisis on a political elite so entrenched and so self-serving that it threatens to “destroy what’s left of the state.”

Haunted by a 15-year-long civil war that ended in 1990 leaving many grievances unresolved, the tiny nation straddling the Middle East’s political and sectarian fault lines is reckoning with a crisis of identity that was never far beneath the surface. Under a complex power-sharing arrangement that helped seal a peace between warring factions, Lebanon’s president must be a Maronite Christian, the prime minister a Sunni Muslim, and the speaker of parliament a Shi’ite Muslim. The system has engendered chronic paralysis, while sectarian leaders have carved out effective fiefdoms, playing on the fears of the myriad minorities and using their official positions to drive resources toward their own constituents in return for votes and loyalty.

Further complicating the situation is Hezbollah, an Iran-backed militia that has morphed into a powerful political force and is accused by critics of running a state within a state. It’s resisted suggestions that it give up an arsenal believed to be more advanced than the army’s.

Amid all of the political disfunction, Lebanon’s 6.8 million inhabitants could at least count on two constants: a relatively sound banking system and the Lebanese pound’s peg to the U.S. dollar. Both began disintegrating last year as the nation was engulfed in a financial crisis that sent the currency into free fall, prompting the central bank to restrict access to dollar deposits. Fearful of seeing their life savings wiped out, hundreds of thousands of Lebanese took part in weeks of protests that triggered the collapse of the government in October.

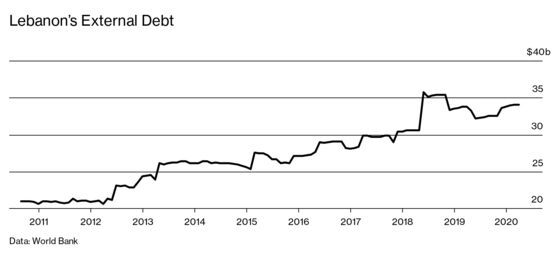

Diab, a career academic, took office in January, having assembled a cabinet composed mainly of technocrats billed as capable of averting a full-scale economic collapse. They quickly concluded that the country wasbankrupt. Lebanon’s habit of financing its perennial budget deficits through borrowing have made it the third-most-indebted nation after Japan and Greece, with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 178% as of the end of 2019. Deeming the debt-service burden unsustainable, Diab’s government defaulted on $30 billion in bonds in March, then turned to the International Monetary Fund for a $10 billion bailout.

Negotiations with the fund never advanced as bankers, politicians, and other vested interests blocked a reform plan that would have forced them to pay for the country’s economic calamity. With talks at an impasse and the nation locked out of international debt markets, Lebanon’s central bank began printing money with abandon, causing the value of the currency to plunge further and igniting inflation, which neared an annualized 90% in June. “We are heading the way of Venezuela,” says Nasser Saidi, a former economy minister.

Prices in the import-dependent nation—including those for food staples, which had soared 250% in the 12 months to June—are no doubt headed higher as a result of the blast, which damaged the country’s main grain silo and other infrastructure vital to commerce. Saidi estimates the country’s imports will drop by more than 70% this year.

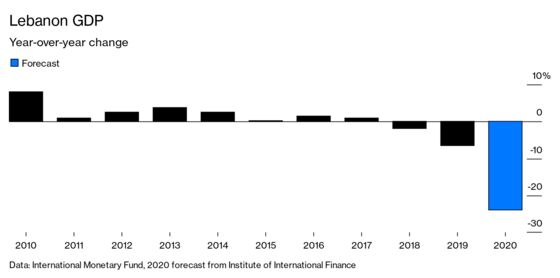

The damage from the disaster exceeds $15 billion, Lebanese President Michel Aoun said on Aug. 12, a figure that amounts to more than 28% of last year’s gross domestic product. In an Aug. 9 report, Garbis Iradian, chief economist for Middle East and North Africa at the Institute of International Finance, wrote that he expects the economy to contract 24% this year.

A virtual conference of aid donors hosted by French President Emmanuel Macron on Aug. 9 drew almost $300 million in pledges, a fraction of the billions it will cost to rebuild the port and city.

It isn’t the first time global powers have tried to throw the country a lifeline. In 2018 a meeting in Paris drummed up $11 billion in commitments. But donors conditioned the release of funds on critical reforms, such as overhauling the electricity sector to put an end to the economically debilitating blackouts that force Beirut’s residents to go as long as 20 hours at a stretch without power. Also high on the priority list: thinning the ranks of a public sector bloated by decades of political patronage. But the politicians ignored these calls, continuing to squabble over everything from jobs to power stations for their own region or religious sect.

Signs that Lebanon had become a failed state were everywhere, even before that reality was vividly rendered in the mushroom cloud over Beirut. Rubbish sits uncollected in the streets as officials fight about whose area it should be dumped in. Streetlights are on in the day and off at night, and traffic lights work only intermittently, leaving motorists to make their own luck on increasingly potholed streets, as they did during the darkest years of the civil war.

In short, government has abdicated its most basic function, which is to protect the citizenry from harm, whether from expired medicines, toxic pesticides, or, as in the most recent consumer scandal, spoiled chicken meat. “Vested interests are so entrenched we need a total mop-up, but that will take time we don’t have,” says Nafez Zouk, lead emerging-markets strategist at Oxford Economics and a Lebanese national. “Is this one of those pivotal moments in a nation’s history where what was not possible before suddenly becomes possible? I’m cautiously optimistic, because if I’m dealing with a corrupt state where I need to pay a bribe, I can live with it, but if I’m dealing with corruption that kills my children, destroys my home, and robs me of my livelihood, then that’s something else.”

The population’s frustration was evident in the hero’s welcome for Macron when he toured some of the hardest-hit areas of Beirut in the aftermath of the blast. Some even drew up a petition inviting the French back to run the country, as they did from 1923 to 1943.

The ruling class “has to be removed. They have to resign and go away. If they don’t go, we will get increasing violence in the street,” says Saidi, the former economy minister. “To do this we need sustained international pressure, from Macron, from others, and if necessary sanctions—international sanctions at the personal level that hit these people where it hurts.”

On his visit to Lebanon, Macron delivered strongly worded messages to Lebanon’s political leaders, demanding they come up with a new social contract and make specific changes that will unlock billions of dollars from international donors. In the meantime, to ensure humanitarian aid reaches those that most desperately need it—instead of lining the pockets of politicians and their cronies—France and other donor nations have said they will channel humanitarian assistance through private charities and international aid agencies.

There are indications that some political players, including Hezbollah, understand the gravity of the situation and are willing to contemplate compromise on sensitive issues, according to three diplomats with knowledge of the matter. Among those is demarcation of sea borders with Israel, which would make it easier for Lebanon to explore for offshore oil and gas deposits.

Saidi’s comparison to Venezuela is apt. There, the divided opposition has been unable to unseat a government that’s driven the economy of the petroleum-rich nation into the ground. In Lebanon, opposition forces have yet to conceive a viable alternative to the sectarian quota system.

“The issue is we never had a post-war reconciliation,” says Mona Fawaz, an activist and professor of urban planning at the American University of Beirut. “There was no accountability for the warlords that now rule us and run this system. So we continue to live in that era with warlords and their cronies who led us into this financial crisis or into regional wars.”

Many are now tempted to join waves of emigration dating back more than 160 years that have given rise to a globe-spanning diaspora. Rather than heading to the Persian Gulf for a spell to work, build up some savings, and then return to their homeland, more are now considering going for good, which could accelerate a brain drain at a time when Lebanon needs its most capable people to take part in reconstruction.

Janay Haidar had planned to go abroad to earn a Ph.D. and then return to Lebanon to start her career. Now, she’s looking to start over in Germany or France. “Everything’s polluted, you can’t breathe clean air, you can’t swim in the sea, you have no electricity, no streetlights, you don’t know if your food will poison you. You can’t get a job, you can’t open a business. Nothing is stable. The blast was the last straw. I have nothing to stay for,” she says. “It breaks my heart, but I need to raise my boys in a place where they can be safe. Where we can live, really live.”

Read more: Lebanon’s Debt Restructuring Put on Ice as Government Resigns

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.