Beijing Winter Olympics Will Spotlight a Richer, More Confident China

Beijing Winter Olympics Will Spotlight a Richer, More Confident China

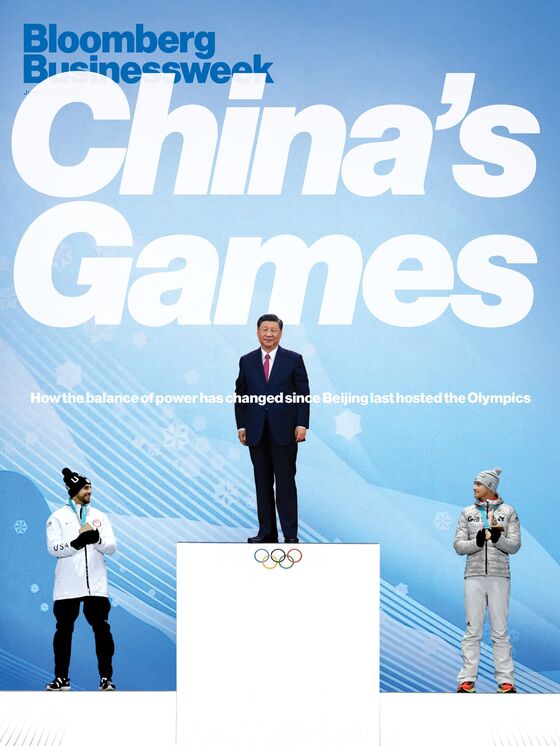

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- For China, hosting the 2008 Summer Olympics was a chance to prove it could hold its own among the great global powers. When the world tunes in for the opening ceremonies of the 2022 Winter Olympics on Feb. 4, a very different China will be in the spotlight.

In 2008 the country had just surpassed Germany to become the world’s third-biggest economy. Its gross domestic product still trailed Japan’s and was only one-third the size of the U.S. economy. Today, China’s GDP is three times larger than Japan’s and steadily closing on the No. 1 spot. If Chinese President Xi Jinping is able to deliver on growth-boosting reforms, and U.S. President Joe Biden’s legislative agenda stumbles, China could overtake the U.S. as soon as 2031, according to forecasts by Bloomberg Economics.

“In 2008, China was desperate to make its case to the world that it belonged on the global stage as an equal,” says Xu Guoqi, a professor of history at the University of Hong Kong and author of Olympic Dreams: China and Sports, 1895-2008. “The message now is China is a strong power. Deal with it.”

Western nations have also done their part to boost China’s confidence. Three weeks after the 2008 closing ceremony in Beijing, Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, setting off a global financial crisis that pummeled economies around the world, China’s included. An estimated 20 million migrant Chinese workers lost their jobs, prompting the government to introduce a 4 trillion-yuan ($630 billion) stimulus package in November 2008. That, along with a surge in lending by the country’s state-owned banks, made China, and not the U.S., the world’s primary engine for growth for the past 15 years. Although the global economy would recover, China’s view of the West never did. The financial crisis “dashed” any illusions that the Western system was “near perfect,” says Henry Wang, who founded the Center for China and Globalization in 2008 and has also served as an adviser to the Chinese cabinet.

For many countries, hosting the Olympics no longer seems worth the cost or the headaches—and that was before the global pandemic rewrote the rules for sprawling gatherings. But enthusiasm for big, expensive international contests hasn’t dimmed for countries such as Russia, Qatar, and China. Critics have said these governments are engaging in “sportswashing”—using the goodwill and excitement of the games to improve their reputation.

To get to host the 2008 Olympics, the Chinese capital beat out Istanbul, Osaka, Paris, and Toronto. And the Communist Party worked overtime to demonstrate that China took its global responsibilities seriously. It brokered a cease-fire in Sudan, invited envoys of the Dalai Lama to Beijing for negotiations, and unblocked access to previously censored websites, including those of Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International.

For the 2022 edition, China’s only competition was Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city, which has recently been engulfed in violent antigovernment protests. Oslo dropped out because the Norwegian parliament refused to fund the games. Stockholm and Krakow, Poland, also pulled out, while referendums passed in Munich and Switzerland’s St. Moritz that barred the cities from bidding.

“If cities in Europe with strong winter sports traditions did not drop out, Beijing would definitely have been a long shot,” says Xu of Hong Kong University. “China hosting these games is, in that sense, a gift from Western countries.”

In the runup to the 2008 games, the International Olympic Committee argued that having China host would push the country toward convergence with the West on issues such as human rights. Instead, today the divergence is as vast as ever, with Beijing wiping away political opposition in Hong Kong and denying accusations of abuses in the Xinjiang region that the U.S. says are tantamount to genocide.

Beijing has steadfastly denied accusations of genocide in Xinjiang and says its efforts in the country’s westernmost province are aimed at fighting extremism. China’s state-run media have described the allegations as part of an effort by the U.S. to suppress China’s rise. Speaking to a group of journalists in Washington in December, Qin Gang, the Chinese ambassador to the U.S., described American actions over the past few years as “a violent attack.” He said “the United States is trying to mobilize allies to kick China out of the international system.”

Susan Brownell, a professor at the University of Missouri at St. Louis and author of Training the Body for China: Sports in the Moral Order of the People’s Republic, says such concerns shouldn’t disqualify China or others as hosts. These Olympics, for example, have made the country’s human-rights record more prominent for a much larger audience than if the games were getting under way in, say, Oslo. “It’s probably a good thing for the games to go to what the pundits call dictatorships,” she says. “I don’t fully subscribe to the idea that the games legitimize dictators—I don’t think the global audience is that stupid.”

Yet instead of bowing to pressure, China is more than ever going on the offensive. That’s been most evident in the increasingly confrontational behavior of the country’s “ wolf warrior” diplomats, who’ve become known for their willingness to engage in verbal scuffles with foreign journalists and government officials alike.

The struggle is broader than them, too. When President Biden hosted officials from more than 100 governments for a virtual gathering dubbed the Summit for Democracy, China responded with a media blitz. Beijing published a white paper days ahead of Biden’s summit arguing that China was a “democracy that works,” then followed up with a forum of its own on democracy featuring speakers from home and abroad.

“Rather than say, ‘Oh, you’re a democracy, so we’re an autocracy,’ China now says, ‘No, we’re a democracy, too,’ ” says Wang. “You have freedom of press, one man, one vote. We have a consultative democracy. We have a meritocracy. But let’s see who did better on performance. That’s the right way to compare.”

And with the Olympics back in Beijing, China is ready for the competition. —John Liu and Janet Paskin

Read next: Wall Street Loves China More Than Ever

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.