MIT’s ‘Beer Game’ Shows Humans Are Weakest Link in Supply Chains

MIT’s ‘Beer Game’ Shows Humans Are Weakest Link in Supply Chains

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Prospects that the world’s snarled supply chains may become less tangled were dealt a setback last month when a couple of MIT students bought 10,000 cases of beer.

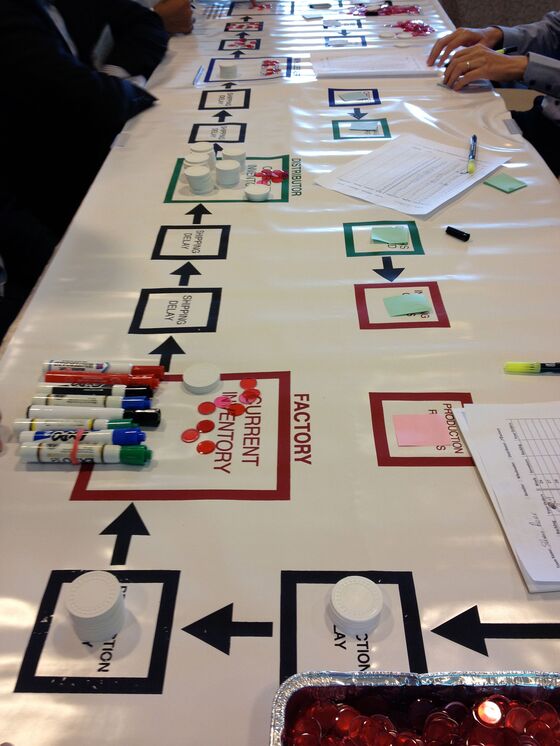

The purchase order wasn’t real. It was part of a role-playing exercise called the Beer Game that’s something of a rite of passage for first-year MBA students at the prestigious Sloan School of Management. Created in the 1960s, it models the supply-and-demand dynamics among a brewery, distributor, wholesaler, and retailer. At the Sept. 24 game, held at a Marriott in Cambridge, Mass., Team Bemba got nervous, made the big buy, and amassed $213,000 in make-believe carrying costs.

The real-life takeaway: The urge to hoard, which has fueled panic buying of everything from flour to microchips, was alive and well in this crop of budding corporate managers. “The pandemic revealed flaws that were latent all along our globalized supply chains,” said management professor John Sterman, addressing the 125 assembled students before the game got under way. “It’s urgent that we figure out how to improve them so we are prepared for the next shocks, whether another pandemic, civil unrest, climate change—or all of the above.”

When the game wrapped after three hours, all 15 of the MIT teams had logged higher-than-average costs. So Sterman shifted the discussion to understanding how such a select group could “all do so badly. And not just badly, but really badly.”

Sterman, who has been running students through the Beer Game for four decades and has written papers about it, compares it to the flight simulators used to train airline pilots. The pandemic has driven home the importance of putting would-be corporate managers through comparable exercises to determine how they’ll react under pressure. “In an aircraft, or a firm, failure is too costly,” Sterman says. “Simulation is then the best, and sometimes only, way we can learn for ourselves how to manage complex systems.”

The Beer Game is designed to teach players about the bullwhip effect, a systems theory developed around the work of Jay Forrester, a computer engineer who joined Sloan’s faculty in the late 1950s. In the simulation, an unexpectedly large order for beer typically sets off a wave of panic orders and inventory building, with the effects amplifying along the supply chain back to the factory

All sorts of bullwhip effects are observable in the global economy right now—ships backed up at U.S. and Chinese ports, Britons lining up for gas, carmakers idling production lines in response to a scarcity of chips. “Fear of running out is causing every company to over-order—like the toilet paper shortage, but at epic scale,” Tesla Inc.’s Elon Musk tweeted in June about semiconductors.

More recently, American retailers have indicated they’re stocking up as much as possible based on expectations that consumer demand will stay strong for the foreseeable future. “We’re ordering as much as we can and getting it in earlier, and I think as evidenced by most recent sales results, we’re doing OK with this,” said Richard Galanti, executive vice president and chief financial officer of Costco Wholesale Corp., on a Sept. 23 earnings call.

As director of Schwarz Asia Pacific Sourcing Ltd., a unit of one of the world’s biggest supermarket operators, Bjoern Lindner buys fixtures and fittings such as shelves, shopping carts, and lighting, and ships them to Europe. “I have no clear predictability on when our goods can be shipped, so the obstacle is transportation from the factory to my warehouse in Germany because there are a lot of uncertainties in between,” he says.

Testrite Group, a Taiwanese trading company that helps American big-box retailers source home goods from more than 4,000 suppliers in markets including China, India, and Southeast Asia, is having to triple inventory levels, especially at U.S. warehouses, because of shipping disruptions. “Traditionally with inventory, the lower the better. But the world is different now,” says Bruce Shen, a spokesman for the company. “An inventory rush like this was very rare before.”

Sterman believes that focusing on Covid-related anomalies as the main source of supply chain strains underplays the cascading effect of bad decisions. “It’s not because of the pandemic. It’s because of the way human beings reacted to the fear that the pandemic induced,” he says. “That’s missing in the supply chain discussion these days.”

That diagnosis resonated with Michelle Diab, a student who took part in the September Beer Game. “The amygdala surges into powerful overdrive with frantic orders for hundreds of units of inventory, high levels of frustration, and blaming the customer,” she says, referring to the zone of the brain associated with fight-or-flight and other survival behaviors. “I was left wondering how it is possible that any organization is capable of any good if this is our human disposition when under threat.”

One of the lessons from the Beer Game is that trust and collaboration are integral to the smooth functioning of supply chains. These can break down when there are production bottlenecks or other types of stresses. For instance, a wholesaler that suspects a usually dependable supplier may prioritize orders from bigger clients is more likely to place duplicate orders with several factories—even if it risks damaging valuable relationships and winding up with too much stock.

Mike Swartz, who played a wholesaler on the winning team, MmmmmmmBeer, says he focused on tracking orders from the retailer and anticipating its needs without sending any bogus signals in the form of an oversize order. The key, he says, was “trusting our teammates and keeping a cool head.” —With Cindy Wang

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.