Automation Actually Creates More Jobs, at Least in the Beginning

Robots are already taking over repetitive human tasks, and soon they’ll come for the rest.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- It’s another day at the emergency room of MedStar Washington Hospital Center in the nation’s capital. Patients are streaming in on foot and on stretchers.

“I used to stand right here,” says Dr. Ethan Booker, pointing to the spot near the door where he once kept watch as the physician in triage. The PIT’s job is to grade human damage. It’s an emotional tug of war: Somebody needs you, but somebody else coming through the door may need you even more.

Technology that Booker helped develop has transformed the way the ER triages patients. When Dr. Jasmine Malek works as the PIT, she’s not even in the emergency room. She’s several buildings away. “I hope you feel better,” she tells a patient via a two-way video link. Her screen also displays a medical history, and, with a few clicks, she can order tests or follow-up treatments.

The system enables faster care. And it hasn’t eliminated jobs. On the contrary, Booker says, “in places where we were successful with this, there was a need for more people.”

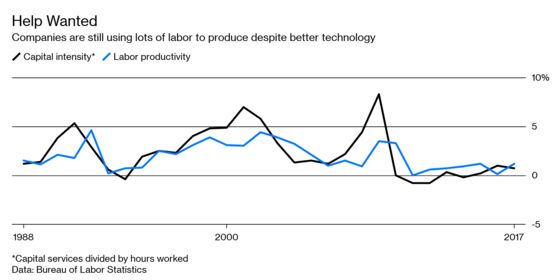

If you listen to techno-dystopians, the outlook for workers is grim. Robots are already taking over repetitive human tasks, and soon they’ll come for the rest. But what’s striking about the later stages of the U.S.’s 10-year-old expansion is how labor-intensive it’s been, with 2.7 million jobs added last year. Smarter machines, it turns out, often require more people.

That may be part of the answer to a question that puzzles economists: How come the steady digitization of almost everything isn’t making the economy more efficient?

New technology is supposed to help countries get richer by making them more productive. But in the U.S., productivity growth—measured as output per hour worked—has been slower in this expansion than in previous ones, suggesting that the tech isn’t delivering.

It’s hard to believe that when you watch Malek in action. She makes tough decisions, directing staff from a serene office with nerdy doctor art on the wall—a picture of the molecular structure of caffeine. It’s far removed from the bedlam of the ER, which is distracting for doctors and slows decision-making. But she can get down there if needed. It’s not like she’s in a call center thousands of miles away.

Triage done this way can handle as many as 22 patients per hour, more than double the old rate, a boon for a hospital that gets about 240 emergency visits a day.

Just about every company in the U.S. is pushing technology more deeply into what they do. They’re doing so at a time of low unemployment and rising compensation, which would normally be expected to eat into corporate margins. Yet profits are holding up.

Ernie Tedeschi, an economist at investment adviser Evercore ISI in Washington, says new technology may explain the contradiction. It enables companies to profit from their new hires. “You’re able to bring in people while you’re making them more productive,” he says.

There’s a school of economics that says this is how big change happens. It’s one that puts innovation center stage and downplays the hydraulics of demand and supply that preoccupy Keynesian and neoclassical economists.

Its dominant figure was Joseph Schumpeter, who argued in the 1940s that “creative destruction is the essential fact about capitalism.” Business-cycle theorist Carlota Perez developed his ideas, describing technological shifts as “a complex collective learning process” in which new and old ways of doing things overlap. During these adjustment periods, productivity measurements might mislead.

That’s how some business executives view tech evolution now. It’s labor-intensive, often a sign of inefficiency, but also labor-enhancing.

Lonne Jaffe, a managing director at Insight Venture Partners in New York, sees this pattern across the portfolio of more than 150 companies the private equity and venture capital firm manages.

For many businesses, capital spending means software that’s enormously scalable because of cloud computing, and cheap. “As prices drop below certain thresholds, entirely new business models get unlocked,” Jaffe says. “It can also unlock new pools of labor.”

There’s a riskier side to all this digitization—but even that creates jobs.

With everything from emergency medicine to vacation planning now online, huge amounts of data are generated. That’s valuable, and hackers are testing every door and window hundreds of times a day. Guarding it is an enormous undertaking that requires a lot of people.

Dan Houston is chairman and chief executive officer of Principal Financial Group Inc., which provides retirement plan services, asset management, and insurance. He budgets about $575 million on technology a year. Some $300 million goes to infrastructure and security, meaning about half is spent on innovations that boost productivity or build connections with clients.

It’s the same everywhere, Houston says: “Everyone is muscling their way through, throwing as much labor at it as they possibly can.”

Eventually, he says, the new data infrastructure and network security foundations will be complete and costs will probably decrease. But that’s still far off. “If this were a nine-inning ballgame, I think we are in the third or fourth,” Houston says.

As chief information and digital officer for Hilton Worldwide Holdings Inc., Noelle Eder is also acutely aware of the security problem, especially after rival Marriott International Inc. was hacked last year. She doesn’t see that as a downside of new technology but more like a flip side.

Eder describes the options available to Hilton guests in a digital age. You’ve traveled a long way, and you’re in no mood for the ritual at reception. So on the cab ride to the hotel you launch Hilton’s phone app and check in—which provides a digital door key. You can also set the temperature in your room, link up your Netflix account to the TV, and order your favorite meal—all before you’ve even arrived.

That personalized experience is only possible if customers share their preferences, which means Eder has to win their trust. She says she devotes a “reasonable majority” of her time to data privacy.

The pace of hiring in hotels and health care has outpaced that in many other industries. New demand is one part of the reason. But new possibilities are another.

Eder says the technology will change what Hilton staff do and “create more time for people in empathy- and judgment-based tasks.” That could be as simple as asking guests over breakfast if there’s anything they need.

“We’re not designing technology to replace humans,” she says. “I’m pretty happy about that. I happen to like humans.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Ben Holland at bholland1@bloomberg.net, Cristina Lindblad

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.