Australians Stick With Their Banks Through Years of Scandal

Australians Stick With Their Banks Through Years of Scandal

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Over the past several years, Australia’s financial industry has been gripped by a series of scandals involving everything from mortgages to investment advice. A sweeping government-ordered inquiry into misconduct lambasted the industry for letting down consumers.

In an effort to force big banks into line, policymakers want to give consumers a chance to vote with their deposits. The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, the watchdog for lenders, licensed five new online banks in 2019, with more expected this year. In July an “open-banking” initiative will make it easier for people to take their money elsewhere. For now, though, customers seem unmoved.

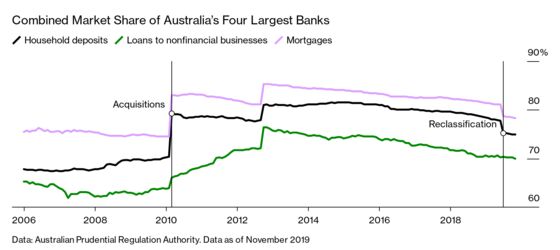

As of December, roughly 7 out of 8 Australians said they had no interest in trying a digital alternative to the country’s four biggest banks, according to data from RFi Group, a retail banking consulting firm. Australia & New Zealand Banking Group, Commonwealth Bank of Australia, Westpac Banking, and National Australia Bank still account for about 75% of the market share in mortgages and customer deposits, frustrating politicians and smaller competitors alike. Market research firm Roy Morgan says that while there hasn’t been a mass exodus, it’s seen a rise in the number of people who say they no longer deal with the major banks. Australians “are outraged, they are devastated by the behavior, by the greed,” Chief Executive Officer Michele Levine said on Bloomberg TV. Even so, she added, “when it comes to their own bank, they kind of like the service.”

Banking customers are notoriously hard to poach because moving accounts can be a headache. About half of Australians are still with their first bank. “People don’t know what really good banking—what smart banking—looks like until they try it,” says Rob Bell, CEO of 86 400 Ltd., which started taking deposits in 2019. The newcomers are trying to gain a foothold by offering such services as bill payment reminders and accounts that can be opened quickly without paperwork. They also offer higher interest rates; 86 400, a reference to the number of seconds in a day, is offering 2.25% on savings, triple the benchmark interest rate set by Australia’s central bank. Another newcomer, Volt Bank Ltd., is paying 2.15%. The best rate on offer from the legacy banks is 1.7%, according to the comparison site Finder.

Still, the large banks have been working hard to keep customers happy. ATM charges, one of the fees that most annoyed consumers, are gone. Commonwealth Bank—which has apologized for breaching anti-money-laundering laws, charging customers for services they didn’t receive, and selling inappropriate insurance—is among those trying to prove it’s changed. In October it quietly deposited A$50 ($34.48) into accounts hit by a service outage, and it’s created a cash-back rewards program. All the big banks are investing heavily in digital services.

Small businesses may offer an opportunity to the new banks, says KPMG’s Ian Pollari. They’re more accustomed to banking with more than one institution, he says, and, compared with consumers, “typically take a more objective approach to deciding between providers.” Joseph Healy, a co-founder of Judo Bank, which focuses on small-business lending, pitches that his bank can offer more personalized service and faster lending decisions. The big banks “have stripped a lot of cost and skills out of their business model and centralized a lot of things into call centers,” he says.

Australia’s regulators hope that open-banking rules will help new entrants and smaller banks. The idea of open banking is to make it easier for consumers to give a third party access to their financial data. If, for example, consumers can share their transaction histories at the touch of a button, that could allow quick credit assessment and offers from other providers, reducing the friction of switching.

A similar effort by the U.K. government after the global financial crisis has had a sometimes bumpy road. Shares of Metro Bank Plc, launched in 2010, hit a record low last year after regulators probed how it measured the risk of some assets. Virgin Money U.K. Plc suspended its dividend to shareholders in November. Even so, several startups have attracted investors and customers with their promise to do things differently in the U.K. Revolut Ltd., which focuses on making it cheaper to spend money abroad, has 8 million customers. Monzo Bank Ltd. boasts that 40,000 people a week are opening an account. Both companies have yet to turn a profit—or even forecast when they will.

If Australia’s smaller banks can get large enough to stay viable, they can become significant for the whole system, says Melisande Waterford, head of licensing for regulator APRA. “Their existence alone can force incumbents to up their game,” she told an industry conference last year.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Pat Regnier at pregnier3@bloomberg.net, Janet Paskin

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.