Australia’s Inward Turn Earns a Faster Rebound Than Expected

Australia’s Inward Turn Earns a Faster Rebound Than Expected

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- A year of border closures is making Australia rethink its embrace of globalization. Before Covid, the country’s economic strategy was predicated on attracting large numbers of immigrants, foreign students, and tourists to supplement earnings from mineral and farm exports. The formula yielded a record-setting 28-year streak of uninterrupted growth and a society where more than half the population was either born abroad or has at least one immigrant parent.

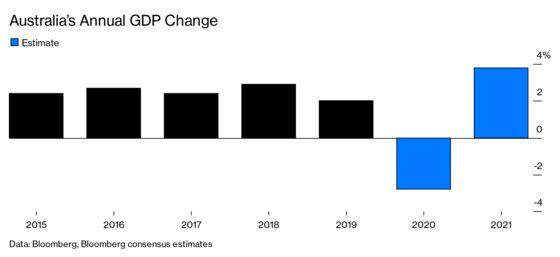

Then the pandemic hit, ushering in strict controls on international travel, followed by a diplomatic brawl with China, the destination for about one-third of Australia’s exports. The country suffered its first recession in decades last year, yet the central bank is now forecasting that gross domestic product will return to its level at the end of 2019 by the middle of this year, which is 6 to 12 months sooner than it had previously anticipated.

How did this happen? First and foremost, coordination between the federal and state governments has been effective in curbing the spread of the coronavirus, so there’s been less need for lengthy lockdowns. The country has recorded 114 Covid-19 cases per 100,000 people since the start of the pandemic, according to the World Health Organization, compared with 8,548 per 100,000 in the U.S. Australia was also quick to do a big fiscal stimulus, pledging the equivalent of 10.6% of GDP for wage subsidies and cash handouts to households and businesses.

But another big reason the economy has rebounded so quickly is that Australia turned inward—more by necessity than choice. Winemakers and other export-oriented businesses pivoted quickly to build domestic sales, and thousands of Australians packed cars and caravans and headed out to spend their money in the Outback or along the country’s vast coastline. “The ban on Australians traveling has diverted around A$45 billion ($35 billion) into domestic discretionary spending or increased household saving,” says Saul Eslake, an independent economist. “That’s more than offsetting a A$25 billion decline in spending in Australia by foreign visitors.”

Looking back on the past 12 months, Alister Purbrick is amazed that Tahbilk, his family’s 161-year-old winery in the state of Victoria, has come through more or less intact. “If you’d have said in February last year that we were going to have the twin challenges of the pandemic and China essentially shutting its market to us, I think I probably would’ve had a nervous breakdown,” he says.

Before the outbreak, Tahbilk had been sending a quarter of its exports to China, which announced at the end of November that it was imposing tariffs of as much as 212% on Australian wine shipments. Although Beijing justified the duties by saying that Australian winemakers had been dumping product in China, the move was widely seen as retaliation for Prime Minister Scott Morrison joining a chorus of world leaders calling for an investigation into the origins of the novel coronavirus.

Fortunately for Tahbilk, Australians have upped their intake of national wines. “People decided ‘we’ve got to eat at home, so we’re going to drink. OK, let’s buy more and buy well,’” says Purbrick, who saw sales via online wine clubs surge 60% in the nine months through January, from a year earlier. “People were trading up, not down as you might have expected in a crisis.” (For Tahbilk and the rest of the industry, a 22% jump in exports to Europe in 2020 also eased the pain of being shut out of China.)

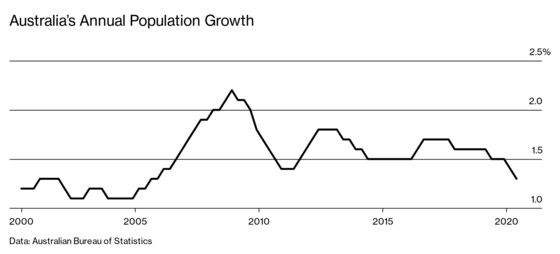

The economy’s surprising resilience has become fodder for a national debate on whether the nation of 25 million needs to undertake a course correction. Discontent with Australia’s expansive immigration policies had been building for years, fueled by rising home prices and growing congestion on roadways and public transit, as well as by reports that newcomers are beating out citizens in the competition for jobs. “I think Australia pre-coronavirus was in the midst of a dangerous experiment,” says Salvatore Babones, a sociologist at the University of Sydney. “This crisis is an opportunity for Australia to dial back immigration to still world-beating, but more modest, levels.”

In an opinion piece published in May, Kristina Keneally, who is part of the leadership of the opposition Labor Party, wrote: “When we restart our migration program, do we want migrants to return to Australia in the same numbers and in the same composition as before the crisis? Our answer should be no.”

Australia’s decision last March to close itself off to foreign travelers has already forced a reset—albeit a temporary one. Its population had been forecast to expand 1.7% in the fiscal year that ends June 30. The central bank now expects the figure to amount to just 0.2%, the lowest level since World War I.

Part of the drop reflects the absence of tens of thousands of international students, mostly from Asia, many of whom become residents after graduation. Education is Australia’s fourth-largest export, contributing $A37.6 billion in the 2018-19 fiscal year. Yet Gigi Foster, an economics professor at the University of New South Wales, argues there are hidden costs, too, saying her research shows that having a high proportion of non-English speaking students in undergraduate classes degrades the quality of instruction and contributes to grade inflation. The pandemic, she says, is giving Australia an opportunity to recalibrate: “There’s not huge hordes of people coming in, so you can think about what you really want to do.” Foster, who moved to Australia from the U.S. in 2003, would like to see the government and universities raise the bar for international entrants to attract a more “elite” group.

One area where Australia has become more selective is investment. A law approved last year gives the Treasury the right to block deals even if they’ve been blessed by the Foreign Investment Review Board. In August, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg availed himself of his new powers to block China Mengniu Dairy Co.’s acquisition of Lion Dairy & Drinks. Then in January, he nixed a $300 million takeover of building contractor Probuild on national security grounds.

Will the urge to splurge on wine at dinner fade once government stimulus runs out? Will millennials keep heading to Byron Bay once borders reopen, instead of jetting off to Fiji? And will the country continue to turn away Chinese investment if Beijing and Canberra patch up their differences? It’s too soon to tell, but at some point Australians will have to decide how much they want to return to their old ways.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.