Atlanta Startup Sees Single-Room Rentals as Future of Low-Cost Housing

Atlanta Startup Sees Single-Room Rentals as Future of Low-Cost Housing

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Rentals with single-room occupancies, once a staple of urban housing, were largely zoned out of U.S. cities decades ago. An Atlanta startup called PadSplit thinks they’re ready for a comeback: The company is helping landlords turn rental properties into pay-by-the-week rooming houses. They already manage more than 400 rooms, mostly in lower- and middle-income neighborhoods of single-family homes.

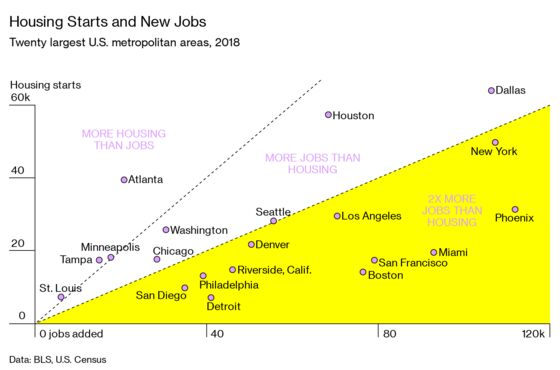

“We’re investing in this because we have basically come to believe that there is going to be a housing crisis again,” says Arjan Schütte, founder of Core Innovation Capital, a venture capital firm that’s backing PadSplit. “Ten years ago the crisis was a financial one. This time it’s a crisis of supply.”

Founded by Atticus LeBlanc, PadSplit instructs landlords on how to convert properties into PadSplit-branded lodging and then manages them for a fee, working inside loopholes in local laws. For example, although Atlanta doesn’t allow rooming houses in single-family-home neighborhoods, PadSplits are designed so that the tenants meet the city’s complicated definition of a “single family”: up to six unrelated people, plus another four, as long as the latter occupy no more than two rooms.

PadSplit roomers get a furnished bedroom; use of bathrooms, kitchen, dining, and laundry rooms; all utilities; wireless; and a cleaning service for about $140 a week, which is collected electronically. A typical home has 5 to 8 furnished bedrooms. PadSplits are deliberately located near bus stops and look like neighboring homes from the outside. Inside, they have fresh paint, granite kitchen countertops, modern appliances, and new laundry equipment. They have no living rooms. Children are allowed, but the economics don’t work for families of more than two people, since they’d need to rent more than one room. And limited bathroom space means most rooms have a single occupant.

LeBlanc plans to spread the concept to other markets; he estimates at least 14 million people in the U.S. are candidates for PadSplit-type housing. He says he’s targeting as clients “the thousands of mom and pop investors out there taking rent.” The pitch is that owners can see their investment returns jump to 9%, from 6%, because the PadSplit system carves up interior space more profitably and installs energy-saving technology such as controlled thermostats and low-flow toilets. And landlords don’t end up with an entire vacant unit when a tenant leaves. A six-bedroom house that stays fully rented can take in $43,000 in annual revenue.

Traditional single-room-occupancy lodging became synonymous with slum housing, and by the 1990s more than a million SRO units had disappeared. Many cities either ban them or limit where they can go. LeBlanc, who describes his business as mission-driven, says he’s reviving them as an affordable option for those at the lowest rungs of the workforce. Some 40% of PadSplit’s roomers were homeless and working full time before moving in, LeBlanc says. “I’m talking security guards, anyone in food service or hospitality,” he says. “The question is whether the people who serve your community can live there.”

The PadSplit concept doesn’t sit well with some in the majority-black, single-family neighborhoods where the company started. At one community meeting in June, City Councilwoman Andrea Boone called for a show of hands merely to let LeBlanc speak. “We do not appreciate the fact that we woke up one day and found that a PadSplit was being advertised in our community,” she said. PadSplit’s roomers also lack the legal protections tenants have. They have no long-term leases and can be evicted instantly.

Housing experts are divided. Chris Ptomey, director of the Urban Land Institute in Washington, says advocates have been hoping “co-living” arrangements could expand to low-wage workers at a larger scale. “I think there’s a lot of hope that these kinds of models could work at a lower price point,” he says. “I think it’s a great, novel model if it can be additive, if it can add units that are affordable.”

But Georgia State University professor Dan Immergluck says PadSplit is mainly a testament to the severity of the housing situation. “It’s kind of a market solution, I guess, for the affordable housing crisis, to get one room, on a week-to-week basis, that really could be yanked out from under you at any time,” he says. “It’s a logical market response to a desperate need among single, low-income people. It’s designed for people earning $10 to $12 per hour.”

One risk is that PadSplits could draw rentals out of the more family-friendly Section 8 program, which provides federal subsidies for renters. LeBlanc says he’s helping landlords take properties that would otherwise be flipped and making them available to low-income renters, instead of gentrifiers. “We needed to demonstrate to investors that truly affordable housing could actually be more profitable than other market-rate alternatives,” LeBlanc says. Immergluck thinks this effect could eventually run out of steam, as property values keep going up and selling becomes more profitable than running a PadSplit.

More than half of metro Atlanta tenants spend more than a third of their income on rent, according to the Atlanta Regional Commission. The area’s rents rose more than those in all but two urban markets in the U.S. last year. Although Atlanta has been adding housing, much of it has been on the high end: The region ranked third in the percentage of new construction going to luxury rentals, at 90%. “The gravitational pull for almost everyone is to do everything upmarket,” says Schütte. Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms won office in 2017 pledging to fix the affordable housing shortage. In June she announced a $1 billion plan to create or preserve 20,000 new units of affordable housing by 2026. LeBlanc predicts PadSplit rooms will contribute 8,000 of them.

LeBlanc got into the low-income rental business in 2007, when the housing crisis flooded Atlanta’s black neighborhoods with foreclosures. “It was almost as if a bomb had gone off in Southwest Atlanta, and no one was talking about it,” he says. Starting with a $70,000 line of credit, $230,000 from family and friends, and high-interest “hard money” loans, he bought 100 single-family homes and 450 apartments. Most of his own rentals, then and now, were part of Section 8. He got $750,000 from the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Neighborhood Stabilization Program in 2009 but found the program cumbersome and slow. Then he began looking for another approach to affordable housing.

LeBlanc got the PadSplit idea from a man who was being kicked out of a shabby, illegal rooming house next door. The man wanted to rent a single room in LeBlanc’s house and pay by the week. Some PadSplit renters may never afford anything else, he says. Others move on, as did security guard Tiffany Ellis, who came to PadSplit from a dicey cheap motel. “It felt so safe there,” she says of the PadSplit. She paid off two credit cards, bought a used car, saved a security deposit, and then found her own place.

The concept is catching on with landlords. PadSplit has 300 more rooms in development, up from 100 in the works in July. Atlanta real estate agent Josh Stanton is buying homes to convert with partners in New York and London, and says he’s out to persuade other investors to buy homes to turn into PadSplits. “When you boil this down, it’s simply an amazing bottom line,” he says.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Pat Regnier at pregnier3@bloomberg.net, Anita Sharpe

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.