Atlanta Attracts Wealthy Black Transplants, But Locals Languish

Atlanta Attracts Wealthy Black Transplants, But Locals Languish

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- It’s a Tuesday afternoon in January, and Ryan Wilson is holding court at the Gathering Spot, a sleek co-working space and business networking club that sits on the site of an old railway yard west of downtown Atlanta. Dressed in a jean jacket, hoodie, and Salvatore Ferragamo sneakers—Wilson’s take on the uniform of a Silicon Valley chief executive—the club’s 28-year-old co-founder surveys the room, acknowledging the city’s new power players with waves of his hand. The director of a six-day hip-hop festival swings by his table to chat about potential business ventures. Passing by is one of the creators of Partpic, an app she sold to Amazon.com Inc. Seventy percent of the club’s members are black. “Part of what the Gathering Spot proves day-to-day is we are not a second-tier market in the way that people have traditionally thought about the city,” Wilson says.

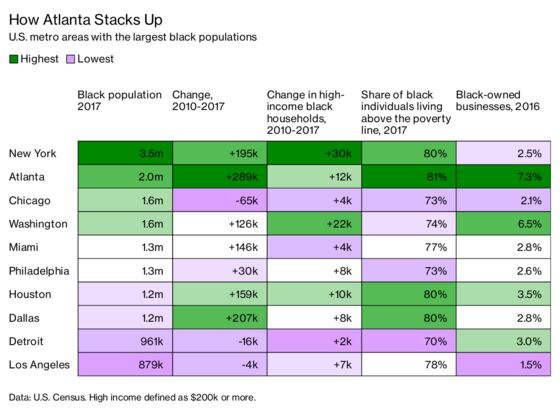

As the multimillion-dollar extravaganza that is the Super Bowl descends on Atlanta for the first time since 2000 (and the third time in its history), the Gathering Spot is emblematic of the city’s ascendant role within the black community. Between 2010 and 2017, the black population here soared by 288,600—far and away the biggest such gain of any U.S. metropolitan area.

Many of the recent migrants were drawn here by the presence of creative types. Some of the biggest names in hip-hop, including Ludacris and T.I., call the city home, as do movie producers Tyler Perry and Will Packer. A source of local pride is that Black Panther, a Marvel film with an almost entirely black cast, was filmed in and around Atlanta.

While some are coming because of the entertainment scene, many are drawn here by the metro area’s comparatively hot economy, which averaged growth of 3.7 percent in the five years through 2017, the most recent data available. The number of black households earning at least $200,000 has jumped 145 percent since 2010, U.S. Census data show, besting the overall U.S. rate of 107 percent. Atlantans are among the most enterprising of America’s blacks—more than 17 percent are self-employed, essentially putting the city in a tie with New Orleans for the No. 1 spot, according to a study by the Center for Opportunity Urbanism.

One of the Gathering Spot’s luminaries is Jewel Burks. A native of Nashville, Burks was working in customer service in 2012 at a company that sold industrial supplies such as fasteners. She was fielding angry calls about misidentified parts when she got the idea of creating a digital tool that could identify different types of screws from photos. She brought in a co-founder and went poking around the Georgia Institute of Technology looking for talent to actually develop the software. A few years later, after raising a couple of million in investment capital, she sold Partpic to Amazon.com for an undisclosed price.

“When I moved out to Silicon Valley, I felt like I was one of the only black people I’d see for days,” says Burks, who worked in sales at Google for a time. She found inspiration in seeing other black entrepreneurs after relocating to Atlanta. “You feel there’s a higher likelihood you can do the same.”

Corporate America has taken notice of the growth and the aspiration, shifting marketing and investment dollars from New York and Chicago south to Atlanta. Procter & Gamble Co., for instance, acquired Walker & Co., a Palo Alto company that markets health and beauty products to blacks, in December and plans to move it here by the middle of the year so it can be close to its target customers. French cognac maker Martell & Co. took over a luxury condo in downtown Atlanta a year ago, where it invites celebrities and other “influencers” to parties. The goal is to burnish Martell’s brand among blacks and Asians, both key customer groups in the U.S., according to brand lifestyle manager Karim Lateef. “I don’t think there’s any perfect city, but this is the city that gives you the best shot, especially if you’re black,” says Wilson’s business partner, TK Petersen, a native of St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands who moved to Atlanta in 2015.

The city is full of enterprising transplants. Erik Gordon grew up in Stockton, Calif., attending meetings of Jack and Jill of America, a leadership development club for black children. Now 38, Gordon—inspired by a late 1980s sitcom—moved to Atlanta in 1998 to attend one of the area’s historically black colleges. “I wanted to come because I saw A Different World, and my friends told me HBCUs were like Jack and Jill conferences. I said, ‘I’m going to Atlanta,’ ” recalls Gordon, a marketing consultant whose iPhone holds more than 2,000 contacts, ranging from entrepreneurs and lawyers to entertainers such as rapper Waka Flocka Flame.

The Koo Koo Room, a speakeasy-like club tucked among midtown Atlanta’s office towers, is just getting its vibe around midnight on a Tuesday night as Gordon arrives. He quickly begins working the room, where two young women, laboring to speak over the din of hip-hop, identify themselves as two-thirds of an up-and-coming girl group called Levi Johnson. Ludacris’s manager is here. Basketball great Charles Barkley, who films Inside the NBA in the city, is squeezing his way toward the far corner of the bar.

Many in the crowd work for entertainment companies, such as BET Networks, or do publicity for them. Almost all are millennials. From 2010 to 2015, Atlanta logged the biggest gain in black young adults among U.S. cities, adding almost 54,000, according to a 2018 report by Brookings Institution demographer William Frey. Dallas ranked second with about 41,000. Chicago and Detroit saw their black populations shrink in recent years, confirming there’s been a reverse migration of blacks back to the South.

Atlanta has been a draw for African Americans since the years following the Civil War, when northern white missionaries and southern blacks swarmed the city in search of jobs and opportunity. Its tag as a “Black Mecca” dates to at least the 1970s, when lawyer Maynard Jackson became the city’s first black mayor and demanded a bigger share of the budgetary pie for blacks, particularly in building and operating the municipally owned airport. (The primary hub for Delta Air Lines, Atlanta’s airport is now the busiest in the world.) The portion of city contracts awarded to minorities soared from 1 percent to 39 percent during Jackson’s first term in office, which, along with more subcontracting work at the airport for minority-owned businesses, helped expand the class of well-to-do black people. In his second term, Jackson also had a hand in clinching Atlanta’s bid for the 1996 Summer Olympics, an event that earned the city renewed attention in the eyes of American corporations.

Still there are those who say Jackson and a string of black successors have made creating a welcoming environment for businesses a priority over policies that bridge the gap between the haves and have-nots. “If Atlanta has progressed, it’s for a very small minority,” says Illya Davis, a professor of African-American studies and philosophy at the historically black Morehouse College. The percentage of black households in the Atlanta metropolitan area earning under $25,000 a year is 22 percent, compared with 13 percent of white households.

Atlanta ranked second-worst in upward mobility for all races over the past two decades in a research paper published last fall by Harvard University economist Raj Chetty and several co-authors that covered 50 U.S. metropolitan areas. Only Charlotte afforded disadvantaged children less opportunity to move out of poverty, the study found.

Chetty spoke to the city’s community leaders in October at the invitation of Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta President Raphael Bostic, the first black Fed president in the central bank’s history. The academic says the big gaps in wealth, in large part a legacy of decades of segregation, are “potentially changeable” because Atlanta’s continuing high growth rates in employment and wages provide abundant opportunities for high-paying work.

Out-of-town strivers are one of the forces shifting Georgia politics, turning the state’s reliably red electorate a purplish shade. In November black state legislator Stacey Abrams lost Georgia’s gubernatorial race by slightly more than 1 percent to her white Republican challenger, Brian Kemp. She captured 65 percent of the vote in Atlanta, and got 766,000 more votes statewide than did the Democrat who ran for governor four years earlier—President Jimmy Carter’s grandson, Jason Carter.

Jessica Stewart studies patterns of African-American migration and, as a black person moving to Atlanta later this year to join the faculty of Emory University, she’s part of the trend she’s researching. Many of Atlanta’s black migrants have come from New York and Chicago, with a smaller number coming from Los Angeles, Stewart says. Plentiful jobs and affordable housing provided the initial pull, but less tangible factors, such as the city’s network of graduates from historically black colleges, play a role.

“It contributes to the feel of Atlanta,” she says. “A city where blacks feel appreciated and celebrated and where there’s a strong black culture that permeates the whole city, and not just some neighborhoods, like the South Side of Chicago.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net, Anita Sharpe

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.