Ask Any Stock Market Pro: Buying Is Easy, Selling Is Hard

The monkey traders should be given the darts when it’s time to sell holdings, not when deciding what to buy.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Princeton economist Burt Malkiel is famous in investing circles for suggesting that blindfolded monkeys throwing darts at a newspaper’s stock pages could build a portfolio that would do just as well as one chosen by expert money managers. A recent academic study suggests that the blindfolded monkeys actually may do even better than the average institutional investor. However, the monkey traders should be given the darts when it’s time to sell holdings, not when deciding what to buy.

The researchers looked at more than 4 million trades among 783 portfolios from 2000 to 2016 and found that stockpickers actually showed skill when buying. However, the sales by these institutional investors cost them as much as 100 basis points, or a full percentage point, of yearly returns compared with a no-skill strategy of simply selling holdings at random, according to the study Selling Fast and Buying Slow by researchers from the University of Chicago, Carnegie Mellon University, MIT, and portfolio analytics firm Inalytics Ltd. The study concluded that one of the likely reasons for the discrepancy was “asymmetric allocation of cognitive resources.” Translation: Investors spend way more time analyzing what to buy than what to sell.

Monkeys with darts would have one big advantage over human fund managers when it comes to selling. The animals wouldn’t get emotionally connected to the stocks in their portfolio. Some professional investors know they have this kind of behavioral bias and take steps to correct it. Their methods can be pretty complicated.

At New York-based Edgewood Management, primary coverage of a stock holding is taken away from the original portfolio manager and given to another member of an investment committee when certain criteria are met, such as two straight quarters of disappointing earnings. At Sierra Mutual Funds in Santa Monica, Calif., Chief Investment Officer Terri Spath advises portfolio managers to employ trades known as “trailing stops,” which are standing orders to sell any stock that falls by a certain percentage. Jerry Dodson, founder and chairman of Parnassus Investments in San Francisco, says he tries to determine each stock’s intrinsic value, then buys shares when the price falls to 67 percent of that value and sells when they reach 100 percent.

Dodson has had good results lately—his $4.1 billion Parnassus Endeavor Fund has beaten 91 percent of similar funds over the past five years—but it’s hard to know how much of this is because of his selling technique. Decisions to sell in general aren’t well-studied, especially by investors themselves, according to Michael Ervolini, co-founder and chief executive officer of Boston-based Cabot Investment Technology, which makes software that analyzes equity portfolios. His firm has scrutinized almost $3 trillion in investments and found that one-third of portfolios exhibit what is known as the “endowment effect,” or a tendency to hold on to a winning stock for too long after it stops outperforming. His work leads him to agree with the main takeaways from the academic research, he says: “Managers know more about, and are better at, their buying and know less about, and are not as good at, their selling.”

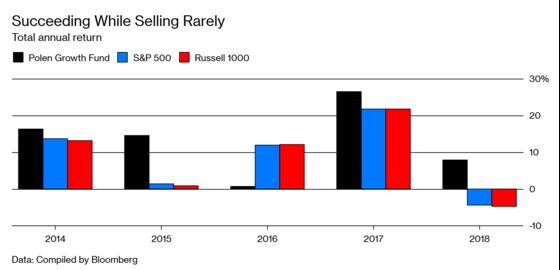

“The way people learn to sell is largely from the people they worked with when they were young—it’s not calibrated,” Ervolini says. “It’s either folklore or heuristics”—that is, mental shortcuts typically learned by trial and error. One of Cabot’s clients is Polen Capital in Boca Raton, Fla., which has found success by not selling too often. It runs a growth fund with a concentrated portfolio of only about 20 companies. Over 30 years, portfolios the company has run with this strategy have owned only about 120 stocks, according to Daniel Davidowitz, CIO and co-manager of the Polen Growth Fund. The $2.8 billion fund has beaten 99 percent of similar funds over the past five years.

Davidowitz says he was worried Cabot’s analysis of the firm’s trading might reveal they were holding too long. And it did find that selling decisions were a bit of a drag, costing Polen about 22 basis points per year in the decade through 2017, though in the latter five years the decisions got better, contributing a net positive 32 basis points per year. “What they’ve told us is that a lot of our outperformance comes in the first three or four years of our holding, and then it becomes a lot more mixed,” Davidowitz says. “So what they are telling us is that, as you get longer into a holding period, especially when it comes to companies that have done well, to keep reevaluting the investment decisions more stringently.”

Davidowitz says Cabot’s system lately has been nudging the managers to consider selling shares of technology consultant Accenture Plc, because “it looks a lot like the kind of company that we held too long in the past.” They’ve reevaluated and decided they still like it. “But we understand why we’re getting the nudge,” he says.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Pat Regnier at pregnier3@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.