As Louisianans Flee Hurricanes, Natural Gas Dollars and Jobs Flood In

As Louisianans Flee Hurricanes, Natural Gas Dollars and Jobs Flood In

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- If you drive far enough down through southwest Louisiana, past the petrochemical plants and the wide marsh to where the road ends at the Gulf of Mexico, you’ll find Cameron, a little town of oystermen and shrimping boats. It’s right near the Chocolate Milk Beach, which is what I called Holly Beach back when I was a kid and my dad would drive us there, 40 miles south from our home in Lake Charles, stopping for shrimp along the way. I didn’t know back then that the water’s Yoo-hoo color was caused by sediment dredged up so places like Lake Charles could have a shipway and an economic lifeline.

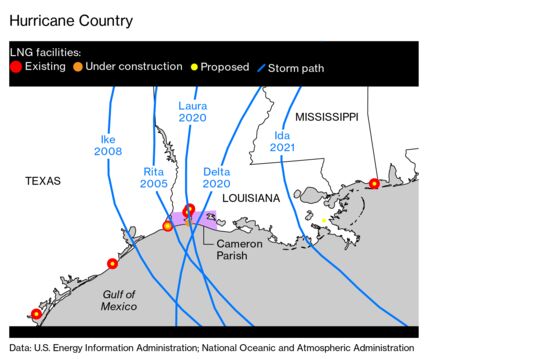

Today the communities of Cameron and Holly Beach look a lot different. In late August 2020, Cameron Parish, where they both lie, was hit square-on by Hurricane Laura. Six weeks later it was lashed by Hurricane Delta. Laura’s 150 mph winds peeled off roofs and smashed holes in brick walls. Into those wounds poured Delta, bringing more wind, 17 inches of rain, and a 9-foot storm surge. Half-done repair jobs—patched-together siding, new drywall, jury-rigged front doors and windows—were destroyed, along with the life savings of many families.

Lake Charles, the region’s hub city, was left unrecognizable. When I visited the morning after Delta, I found glorious, Spanish-moss-dripping oaks rotting roots-up in friends’ front yards like dead roaches. Tall pines had snapped in half, and magnolia branches were clogging the drainage ditches where I once caught crawfish. What remained were homes with blue tarp roofs, microwaving under the bright, hot sky. “It’s like someone turned on the lights here,” one resident said.

The sad waltz of southwest Louisiana had only just begun. A few months later the historic freeze that knocked Texas offline struck the crippled communities across the state line, too. Some people here spent 18-degree nights shivering in roofless homes as the death toll—from hypothermia, exposure, carbon-monoxide poisoning caused by generators—rose. The lucky ones who’d skirted the storms with only a lost fence or a roof puncture now had to deal with burst pipes and weeks without power or water. Then May brought heavy rains and a thousand-year flood, which seemed to be a capstone event on the steady, dire warning from Mother Nature about the hazards of a changing climate.

Hurricane Ida, in August, largely spared the Southwest, but it served as a reminder of the region’s peril. Outside the flood protection system around New Orleans, some communities faced catastrophic, irreversible damage. There are no levees around Holly Beach or Lake Charles, and there’s only so much government can do to keep people dry. For many in these parts, flood protection means pylons, plywood, sandbags, and crossed fingers.

Everyone around here speaks natural disaster. They know when to flee and what can happen if they don’t. Ask anybody you meet, and chances are they lost a grandparent or a neighbor or a cousin in 1957, when almost 400 people were killed by Hurricane Audrey. You might think, given the latest cascade of traumas, that residents would be leaving in droves, and it’s true, most are wrestling with the question of whether to rebuild or start over someplace else. You hear neighbors debating it on porches at dusk, in line at the few remaining grocery stores, in the comments section of the American Press newspaper. Many are going. But people in southwest Louisiana are stubborn about their vision of the good life on the bayou: rocking chairs, a Gulf breeze, and the electric air of a Mardi Gras morning.

And for every family that decides to pack it in and head for high ground, others are rushing in on the counterflow. That’s because, for all the danger the storms pose, the economic opportunities are too good. This region has seen $100 billion worth of capital investment over the past decade, thanks to liquefied natural gas, or LNG. Shale exploration has left the U.S. with more natural gas than it can use, and in 2018 the country turned from a net importer to a net exporter. Already, a little more than half of all U.S. LNG exports flow through two terminals in Cameron Parish, including the country’s biggest, owned by Cheniere Energy Inc. Another 10 major projects are either approved or under construction. The Southwest Louisiana Economic Development Alliance estimates that, between pending and completed projects, 77,000 jobs are being created.

Natural gas is set to overtake coal as the world’s second-biggest energy source by 2035, according to the International Gas Union, and little Cameron is poised to provide. Drive across the bridges that crisscross the swamp at night, and you’ll see a Cajun Emerald City: steam towers and hydrocarbon crackers, lit up in an orangy glow.

So the jobs seem safe, even when the region does not. But some locals hold that the danger itself is a mirage. Many of those who are staying say there’s no proof the storms will keep getting worse. And no, they don’t believe the fossil fuel industry is to blame for recent weather trends—that’s just liberal talk. And fracking equals cash, damn right. Cameron Parish is bright red, voting 90.9% Trump in 2020. This is MAGA country, where for many there is no climate change, just random storms of random strength issued by the heavens, again and again.

Last Oct. 10, hours after the eye of Delta struck Cameron, I was splashing down Highway 27 in hip waders when I noticed the birds. The pelicans and terns were flying twisted and scattered, as though they were still caught in the 100 mph winds, desperately disoriented.

I was lost, too. I was trying to find Tressie Smith’s restaurant, Anchors Up, but with most buildings destroyed or partly submerged and all the signs blown away, the town I’d known since childhood no longer seemed to exist. Smith had asked me to take a photo of Anchors Up so she’d know if there was anything worth going back for. She’d been at a relative’s house in Lake Charles during Laura, texting me as things escalated: “Raining like hell.” “Lights flickering.” “Power off.” When Cameron was evacuated in advance of Delta, Smith got wise and drove all the way to Houston. The morning after the storm, they let the media in, and I told her I’d report back on what I found.

I walked through the main cemetery and saw that the mausoleum was exposed, with rows of empty slots where bodies had once rested; the caskets had floated out into the floodwaters. A little farther along the road, I spotted Anchors Up. The place had lived up to its name, casting off from its foundation and drifting, intact, on the storm surge to the parking lot behind the Capital One, about a block away. It sat next to a stranded shrimping boat like a beached turquoise whale, bags of Zapps potato chips still clinging to racks inside. I sent Smith a pic, but she didn’t write back. Maybe she was busy, or maybe she couldn’t bring herself to reply.

One block over, a home alarm was beep-beep-beeping beneath a pile of debris. The only other sound was the rhythmic lull of waves lapping against the remains of people’s lives. A small herd of newly stray dogs and cats started following me around, meowing and yipping, jumping from one junk pile to the next, hoping for food.

At First Baptist Church, the windows Laura had blown out were replaced by plastic sheets that flapped and swished in the wind. Inside, dozens of folding tables had been set up, with donations sent after Laura stacked high: clothing, loaves of bread, water, diapers. It would have been a heartwarming scene of community resilience, had Delta not swept in. Clothes and diapers were sopped with swamp water, as were the bread slices that littered the floor. Water jugs had fallen and burst. In one corner a whiteboard cheerfully announced, “Take what you need!” It was a picture of compounded sorrow: Cameron hadn’t recovered from the first disaster before the next one hit.

In a sense, that’s how history has played out here for decades. The modern run of megastorms began with Audrey, which made landfall in 1957 between Holly Beach and the mouth of the Sabine River, where Cheniere LNG is located now. Lacking a storm-warning system, advanced radar, Doppler technology, or the Saffir-Simpson category scale and its cones of danger, the people of Cameron only had the word of their local weatherman to go on. Hundreds died.

The day before Audrey hit, the Weather Bureau warned everyone living in “low and exposed places along the beach” to move to higher ground, but many people didn’t, either because they weren’t on the beach or they didn’t believe they lived in a low-lying area. A man named Whitney Bartie lost his family when the storm swept them off the roof, one by one. He sued the federal government, claiming its warnings had been insufficient to the point of negligence. The lawsuit recounts that a TV news broadcast the night of the storm had said “there is no need for alarm tonight” and “you can rest well tonight.” It later emerged that the advice had been intended only for Lake Charles residents, not Cameron, but the words became local legend down here anyway.

So, too, did the accounts of survivors. Archives compiled by the National Weather Service and the Louisiana Digital Library include the story of a man and his niece who “floated out the window” and then were separated by a tidal wave that cast the man, clinging to a piece of wood, 3 miles away. Cameron, population 3,000, was left looking, in the words of Mrs. John R. Smith, “as if no one had ever lived there.” I still remember reading, in the town’s old library (itself since destroyed by a storm), the tale of a child who’d seen a ghost dressed in a long white gown calling his name before water sucked her out the back door. His mother.

Stories such as these have suffused Cameron with a haunted, gothic feel, persisting through a relative quiet spell until Rita (2005) and Ike (2008) pummeled the region in short sequence. With every new storm, people’s relationship to nature frayed further. Many locals carry the trauma defiantly, as a sword against impending reality, insisting on finding ways to stay put, storm after storm after storm after storm. In her 2016 book about southwest Louisiana, Strangers in Their Own Land, sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild calls this attitude the “Great Paradox.” She concludes that people here dismiss skeptics, critics, and reality itself, because they want badly to hold on to the “elation” that comes with living their own truth. But the storms of the past few years are testing that elation like never before.

“I feel powerless against Mother Nature.”

Sarah Guilott-Mcinnis is sobbing in her kitchen in Lake Charles, where she’s opened up her cabinets full of colorful dishes and glass pitchers for a rummage sale with hardly any customers. “I’ve been fighting water for so long. I’m so tired of fixing shit. I feel so defeated.” She gasps between hiccups. “I-I-I just want to leave and start fresh somewhere else, anywhere.”

Guilott-Mcinnis had a baby right before the pandemic hit. A few months later she took over the laundromat business her grandfather had started, only to watch the virus drive customers away. “I thought that was the worst of it—Covid plus a baby plus a failing business,” she says. “Then the hurricanes began.”

In August, Laura ripped down the chimney and many of the eaves of her home, a midcentury geodesic dome with a sunken den. Six weeks later, when Delta dumped its record-setting 21 inches of water in Lake Charles, the rain streamed down the inside walls—“like from a faucet,” Guilott-Mcinnis says—and drenched the bedrooms. Come February, the freeze caused a pipe to burst. She and her husband had to rip down a wall by hand so they could stanch the spray.

In May, Guilott-Mcinnis was dropping off her baby at her mom’s when she got stranded by high water from the random, pre-summer swirl of storms that were bringing the thousand-year flood. Her husband phoned and said the water was up to their front door. Half an hour later came the call she’d feared all year. “It’s done,” he told her. Their home, which she’d bought at 23, poured almost $100,000 into, and blogged about because of its historic design, had completely flooded. The family’s most important possessions were floating around in Tupperware, a precautionary measure they’d taken as the forecast worsened. I notice a foot-high waterline on the doorjamb below where they’d measured the two kids’ heights in green marker.

Lake Charles is a gambling town, with billboards and legends of pirates and buried bullion beckoning Texans over the bridge to its gaudy casinos. And Guilott-Mcinnis was now a four-time loser, one of many. U.S. Postal Service address-change records suggest that Lake Charles lost a greater share of its population in 2020 than anywhere else in the country, shrinking 6.7%. The true figure is likely higher, because registering an address change isn’t at the top of most evacuees’ priority list. Following the May floods the city government estimated that 3,000 of 80,000 residents were displaced, and it wasn’t clear if they’d ever come back. The trend is best described as a climate exodus.

Guilott-Mcinnis and her husband are moving to Fayetteville, Ark. She doesn’t know anyone there, but she heard it was nice.

Down in Cameron you can find signs of a revival, albeit one that’s leaving the town looking much different than it’s ever been. Homes that became debris piles are being raked up and hauled out, and in their place hundreds of RVs have moved in. Many are company-owned: shiny, matching, and new, powered by a humming chorus of generators.

The change has happened fast. Cameron is no longer a deep-rooted shrimping town. It’s become a get-in-and-get-out LNG town, the lodging site for one of America’s most Covid-proof, booming industries. As of this June the local government placed the permanent population at 50 to 75 people, compared with 900 more-transient facilities workers. A gig at one of the plants brings in $1,796 a week, on average, a wage the Cameron Parish port touts as the country’s highest for counties with a comparable number of jobs. In the past 15 years, the parish’s median household income has almost doubled, from $35,000 to $67,000.

Workers are bused daily to the two LNG facilities already operating here, Cheniere and Cameron, and to the six additional developments that are under construction. Right over the border in Texas two more are being built. According to a report from McKinsey & Co. in February, 200 million metric tons’ worth of new capacity will be required by 2050 to meet global demand. A big share of that will be in southwest Louisiana.

On a sinisterly hot afternoon, I toured Cheniere’s sprawling LNG facility, situated on a plateau of old Army Corps of Engineers dredge spoils. LNG is methane gas in liquid form. The gas is piped into southwest Louisiana from fracking sites around the country, then cooled for liquefaction. The liquid takes up one-six-hundredth the space as the gas, making it vastly more cost-effective to export. Once it reaches its destination, it’s heated back into gas form for consumer use. Cheniere is the largest American LNG producer and one of the world’s biggest exporters. China and the European Union are its biggest customers, and Brazil is gaining quick.

Cameron and the Sabine Pass’s position on the coast and in the middle of the U.S. made the site ideal for import terminals back when the country was bringing in LNG. But the fracking boom led Cheniere to retrofit its facilities for export. From the highway bridge that leads to Texas, the plant dwarfs the nearby fishing camps. It features five of the “trains” that liquefy and purify the gas, with one more under construction, and it has five storage tanks that could each fit a 747 inside. There are two ship berths; a third is on the way.

All of this investment has to be protected, of course. After Hurricane Ida made landfall to the southeast in late August, the Coast Guard received thousands of reports of pollution seeping from the industrial corridor environmentalists have dubbed Cancer Alley, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration received 55 spill reports. A similar storm in southwest Louisiana could be even more perilous. Laura threatened 3.5 million barrels per day of refining capacity, according to the American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers, and the flurry of LNG construction has left a vulnerable collection of massive, half-built facilities. The industry has spent millions to safeguard infrastructure in the area, and thus far, it has escaped major damage.

As we tour Cheniere’s facilities in a truck, Amy Miller, the plant’s supervisor for local government and community affairs, who’s also a Cameron local, tells me the buildings are fortified against winds of 150 mph and the cooling trains are elevated 18 feet in case of flooding. The site can also generate its own power if the local grid goes down. Miller points out that employees are required to back in their cars when they park, so they can get out quickly in an emergency. The only time the plant has ever shut down and evacuated completely was during Laura.

After Laura, some of the area’s LNG terminals went offline, but within two weeks feed gas deliveries were again on the move, and cargo ships were churning up and down the Sabine Pass. Delta, the freeze, and the floods saw only a chlorine plant explosion, outside Lake Charles where the petrochemical refineries are—not bad for a place rife with hazmat sites. Before I head back to Cameron, Miller reminds me of how much Cheniere has invested in stormproofing and notes that LNG would “evaporate 100%” if it were to spill.

Within the industry, LNG is seen as a solution to climate change, not a contributor to it. “Natural gas combines high heating intensity and efficiency with low emissions and virtually no pollution,” an executive from the International Gas Union, an advocacy group, said in a 2018 report. In some of the world’s poorest areas it replaces coal or can be used in lieu of cow manure or camel dung. India is set to almost double the length of its gas transmission grid, and China is experiencing record natural gas demand. At least four-fifths of Brazil’s LNG imports come from the U.S.—mostly through Cheniere—and that figure could increase as drought depletes the country’s hydropower reservoirs.

LNG’s boosters often call natural gas a “bridge fuel” that allows for dirtier energy sources such as coal to be replaced now, in anticipation of a future when it will itself be phased out in favor of cleaner energy sources. Environmentalists say that’s Pollyannaish thinking, noting that LNG is the product of a damaging process, fracking, and that methane and other harmful gases can be released during the export process. Transport via tankers adds to the greenhouse gas tally. Additionally, “the massive investments in infrastructure to support this industry,” the Natural Resources Defense Council wrote in a 2020 report, “lock in fossil fuel dependence, making the transition to actual low-carbon and no-carbon energy even more difficult.”

When I mention the word “climate” in interviews around Cameron Parish, people often get uncomfortable and start sizing me up, trying to detect which way my politics lean. Some are blunter than others; one person I interview interrupts me to ask where my red hat is. Trump toured Sempra Energy’s $10 billion Cameron LNG facility in 2019, shortly after signing two executive orders to ease energy industry restrictions, and visited again in 2020 after Laura, touring some of the storm-ravaged neighborhoods with Louisiana’s Democratic governor, John Bel Edwards. “I know one thing: that we’ll provide a lot of what they call the green,” Trump said. “We’re going to have this situation taken care of quickly.” Within weeks, Delta struck, and down in Cameron I was seeing families huddled in cheap camping tents, pitched on the concrete slabs where their homes used to be. Tied to barren pillars that had once supported houses, you could see the bright red flag still flying high: Make America Great Again.

When you don’t believe man-made global warming is creating more frequent and severe weather events, it stands to reason you’ll be more likely to stay in their path. Bronwen Theriot, a science teacher at Cameron’s high school, once told me her attitude: “If it’s God’s will, you’ve got no power to change that.” Her school was rebuilt by the federal government in 2006 after Rita, and it now sits on steel and brick pillars up in the sky. From Theriot’s classroom, students listen to her natural science lessons while gazing out over the front line of climate change, a bare horizon of marsh and the encroaching Gulf of Mexico.

How many hurricanes does it take to change a mind? For Nic Hunter, the 37-year-old, Trump-supporting mayor of Lake Charles, the recent rounds have been enough. “There’s just gotta be a point where you say to hell with politics and just call it like you see it,” Hunter tells me when we meet in his 10th-floor office downtown. “And with what we have been through over the last year, how can you deny that there is something going on?” In a sign, perhaps, that voters are starting to modify their views on climate change, he won reelection in March with 74% of the vote, up from 56% last time out.

President Joe Biden visited Lake Charles in May, right before the floods, to tout his proposed infrastructure funding package. Hunter says they spoke for “six or seven minutes,” during which he asked the president to support supplemental disaster recovery funding for the region. He wanted the federal government to bridge the gap between what the state and private insurance can pay residents. “He seemed very concerned,” Hunter says of Biden. “But ask me in six months if we have the supplemental disaster aid we need, and I will tell you if it was a good or fruitless conversation.”

Hunter didn’t wait that long to start pressuring the government on Facebook. After the flooding, alongside a montage of images of destroyed homes covered in blue tarps, he wrote, “Am I living in the Twilight Zone? Is this America? I took these pictures TODAY on JULY 17, 2021, almost 11 months after Hurricane Laura, 9 months after Hurricane Delta, 4 months after a Winter Storm, and 2 months after a 1,000 Year Flood Event. … Multiply this by 600 and that’s a better picture of southwest Louisiana right now.” He added that federal supplemental aid had arrived in New Orleans 10 days after Katrina and on the East Coast 98 days after Sandy. The situation on the ground, he said, was “a humanitarian crisis.”

For weeks over the summer, the Lake Charles Convention & Visitors Bureau’s Visit Lake Charles website eschewed its usual colorful photos of slot machines and kids holding up baby alligators. A time counter on the homepage ticked off the seconds, minutes, hours, days “SINCE HURRICANE LAURA WITH NO SUPPLEMENTAL FEDERAL DISASTER RELIEF FOR SOUTHWEST LOUISIANA.”

In the meantime, in Cameron, a $32 million project got under way, seeking to scoop 2.36 million cubic yards of sand out of the Gulf of Mexico and plop it into what’s left of the marsh in the name of coastal restoration. It’s a Sisyphean way to approach nature, endlessly lugging sand after each hurricane in preparation for the next one.

Forecasters predicted that the 2021 hurricane season would be major—with 13 to 20 tropical storms, 6 to 10 of them hurricanes. Ida, for one, delivered. In August, as radar showed its red and yellow pinwheel spinning north through the Caribbean toward Louisiana, I checked in on my people. Everyone was on edge. Social media was lit up with expletive-laden posts and “NOT NOW, IDA” pleas. There was a palpable sense that the region simply didn’t have the fight left for another storm. Instead, Ida went toward New Orleans, sparing southwest Louisiana. Local newspapers began pondering whether it would help bring in federal assistance for their region at last, or steal away aid that might otherwise have headed their way—a Louisiana-style hunger games.

On Sept. 7, perhaps goaded by Ida, the White House asked Congress to fund additional relief for southwest Louisiana. A few weeks later the Biden administration said it was authorizing an increase in federal funding to the state for debris removal and unspecified “emergency protective measures” as a result of Laura.

The amount destined for southwest Louisiana is $600 million, far short of the $3 billion the state government had estimated was needed.

Hunter responded on Facebook. “I thank President Biden for his support. Though the final numbers are woefully inadequate,” he wrote. They “represent about 1/5 of what the state estimated our unmet need to be.” And that estimate, Hunter added, was from before the winter storm and May flood.

“Ultimately, we will do what we always do in SWLA. We will never give up,” he said. That elation again.

But the hurricanes keep coming. “There’s a lot of fatigue,” says Andy Patrick, the National Weather Service meteorologist responsible for Lake Charles. “It’s no surprise a lot of people just want to move away.”

In Lake Charles’s Greinwich Terrace neighborhood, the mostly Black residents were given that option in May—quit rebuilding and take a buyout. The community was identified for a voluntary program that’s operated by the Louisiana Watershed Initiative and funded with federal money, after an engineering company found the neighborhood was guaranteed to flood during significant rain events. The residents already knew this: It had happened three times in the past four years, including in 2017 during Hurricane Harvey, which didn’t significantly affect other parts of Lake Charles. “The buyout is the best of a bunch of imperfect options,” Mayor Hunter says. He’s pledged to fight to make sure the residents are offered fair market value.

If everyone leaves, the plan is to remove all the impervious surfaces—concrete slabs and structures—in the area to turn it into a drainage basin for surrounding neighborhoods. In other words, the community is slated to become marshland.

“This is not normal,” Diamond Meche, a Terrace resident, tells me on her lunch break from her job at the Walmart across the freeway. The application period for the program is only just beginning, and she and her parents don’t know how much they’ll get for their one-story brick home, but they plan to take the buyout and join the exodus. The people who want to stay or can’t afford to leave, she says, should expect more problems: “I wouldn’t advise people here to buy furniture, to be on the safe side. And I would advise you to live out of Tupperwares.” Meche still doesn’t know where her family will go.

Down in Cameron, Tressie Smith has converted Anchors Up into a food truck. “I realized that if I was gonna stay here, I needed to be on wheels so I can pick up and go,” she says. The cost of rebuilding to meet new local construction rules that require everything to be up high made it too onerous to root down. The LNG facilities have kept Smith in business. “I depend on that lunch rush,” she says, stubbing out a cigarette. “How else is someone supposed to survive down here?”

She cusses, laughs, and ducks back into the truck as a facilities worker steps up to the window to order. He’s from Seattle, living in a man camp and wearing a work vest from one of the engineering and construction companies building LNG facilities. While he waits for his shrimp basket, he looks around at the piles of tree branches and flattened homes. “There’s nothing here,” he tells me, “but it’ll make you all the money you need.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.