As Cocaine Production Explodes, Colombia Tries to Appease Trump

As Cocaine Production Explodes, Colombia Tries to Appease Trump

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Tara, a bomb-sniffing dog with the Colombian anti-narcotics police, failed to detect the land mine, and the explosion flung officer Jose Carvajal high into the air. When he tried to stand up, Carvajal found that his legs would no longer obey. “When I looked down, my right foot wasn’t there,” he says. “The mine took my leg off below the knee.”

The 23-year-old policeman was one of a group of officers protecting workers digging up coca, the raw material for making cocaine, near the cartel-dominated town of Tarazá in the northern Andes. U.S. President Donald Trump has effectively threatened to cut off loans and other forms of aid to Colombia if it can’t restrain cocaine production, which has more than tripled since 2013.

President Iván Duque’s government has stepped up eradication programs, but the armed groups that profit from the illegal trade are fighting back, planting homemade mines on footpaths and between coca shrubs to protect their investment. At least 11 people have been killed and 84 injured in operations to eradicate coca this year.

The sacrifices Carvajal and his colleagues made might not be enough to appease Trump, who said in March that Duque has “done nothing for us.” The U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy will publish its annual report in the coming days. If cocaine production continues to hit records, Trump may follow through on his threats to “decertify” Colombia as a partner in the war on drugs. This would lump the U.S.’s closest Latin American ally in the same rogue category as Nicolás Maduro’s Venezuela. Under the Foreign Assistance Act, it would also mean that the U.S. would end most economic aid and automatically vote against Colombia’s getting loans from lenders such as the World Bank.

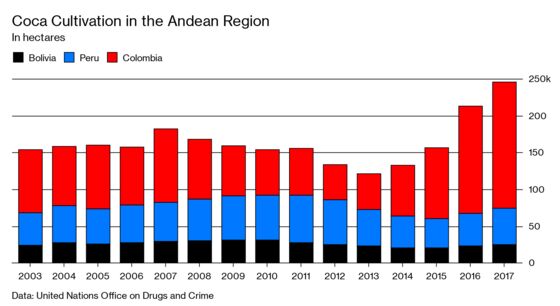

From 2000 to 2012, Colombian coca production fell about 70%, and Peru briefly overtook the country as the world’s biggest producer. But production has soared since then, according to United Nations figures. The trouble picked up in 2015 when the World Health Organization issued a report calling the herbicide glyphosate probably carcinogenic, leading the government to suspend aerial spraying of coca crops. Duque wants to resume the spraying but faces political and legal challenges. Meanwhile, Colombia is growing enough coca to produce almost 1,400 tons of cocaine a year—more than Peru and Bolivia combined.

Decertification is “a more real possibility this year than in any past year,” says Adam Isacson of the Washington Office on Latin America, which studies human rights in Latin America. If coca production rises even 5%, he says, Trump is likely to ignore advice from Latin American experts in the U.S. Department of State who’ve argued against decertifying the country.

It wouldn’t be the first time he’s ignored them. In March, Trump said he’d cut hundreds of millions of dollars in aid to El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras over their failure to curb migration to the U.S. In May he said he’d impose a tariff on all Mexican goods unless Mexico took significant steps to halt immigration from Central America. An eleventh-hour agreement prevented the tariff from taking effect. “The president has been frustrated with the increase in coca production and cocaine production and trafficking ever since he came to office and has looked for ways to signal his frustration,” says Tom Shannon, who was Trump’s under secretary of state for political affairs until June 2018. “The frustration is felt not only at the White House but also in our Congress.” White House representatives didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The U.S. House of Representatives last month recommended that Colombia get $457 million in aid next year, after receiving $418 million in 2019. In its 2020 financing plan, the Colombian government said it plans to borrow $1.6 billion from multilateral lenders. If it were cut off from multilateral loans, the government would have to rely more on issuing bonds, resulting in higher borrowing costs, says Camilo Pérez, chief economist at Banco de Bogotá.

Shannon says decertification would be a mistake, especially because Colombia has been a key ally in the Venezuela crisis. It could turn Colombia into “a pretty reluctant partner” on some issues, he says.

Colombians used to be treated like “pariahs” over drugs, says former Colombian President Andrés Pastrana. In the mid-1990s, not only was the country decertified, but the president at the time, Ernesto Samper, had his U.S. visa revoked after it became known that drug traffickers financed his campaign.

Pastrana oversaw the start of the multibillion-dollar counternarcotics plan known as Plan Colombia with President Bill Clinton. The U.S. has given Colombia more than $10 billion in aid since the program began, more than to any other country outside the Middle East and Asia. But Colombia now produces more cocaine than when the plan started.

Carvajal and his fellow officers are on the front line of the battle to reverse that trend. His unit didn’t have any morphine, so he had to wait in agony for a helicopter to lift him off the mountain. Doctors at the hospital in Montería amputated his other leg. Tara was unhurt, but it was her second major blunder, and the police put her up for adoption.

Today, Carvajal spends most of his days in physiotherapy and learning to walk with prosthetic limbs. “It’s frustrating having lost my legs so young,” he says. “Drugs bring a lot of negative consequences, and not just to people who consume them.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Eric Gelman at egelman3@bloomberg.net, Jillian Goodman

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.