The Woman Who Got Bromine Out of Kids’ Pajamas Fears It’s Coming Back

The Woman Who Got Bromine Out of Kids’ Pajamas Fears It’s Coming Back

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Among the technical and sometimes arcane-seeming debates at this year’s meeting of the International Code Council was one that grew surprisingly emotional: whether building codes should allow the use of polystyrene insulation not treated with flame retardant in foundations, below a 3.5-inch concrete slab. At stake was a larger argument about whether some volatile elements, including bromine, are safer for human health if they’re part of longer chains of molecules. On one side were some of the chemical industry’s most powerful companies. On the other was 74-year-old chemist and activist Arlene Blum.

Blum is an accomplished mountaineer—she led the first all-women expedition to scale the Himalayan massif Annapurna in 1978—and sometimes describes her professional trials in those terms. In 1977 she identified a brominated flame retardant called Tris as a likely carcinogen, leading to a ban on Tris-treated kids’ pajamas. That was a relatively easy climb, at least compared with persuading international standards setters in 2008 not to impose regulations that would have put hundreds of millions of pounds of flame retardants in the casings of TVs, printers, and other household electronics. That, Blum, says, “was harder than Annapurna.”

Most bromine comes from the Dead Sea, as a byproduct of the production of potash, an essential ingredient in fertilizer. It’s useful for rubber production, oil and gas drilling, and pesticides, but its main use is in flame retardants. Albemarle, Lanxess, BASF, and DuPont all make these retardants or products that contain them, and that puts them in opposition to Blum. She “has opposed the use of chemical flame retardants in virtually every application and circumstance,” a spokesman for DuPont says. The EPS Industry Alliance, which represents makers of expanded polystyrene, calls Blum’s work “alarmist.”

After her research led to the elimination of Tris from children’s pajamas, Blum dedicated most of the next three decades to mountaineering, raising her daughter, and writing a memoir. The number and uses of flame retardants increased steadily during that time, however, and in 2008 she returned to science, founding the Green Science Policy Institute. Her advocacy paid off in 2017, when the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission issued what seemed like a blow to the chemical industry, recommending against the use of organohalogen flame retardants—those containing bromine and chlorine. It also recommended that consumers ask retailers for products without them. The commission made one exception: flame retardants that used polymers, atom chains that form larger molecules.

At the International Code Council meeting, held in a hotel in Albuquerque, Blum was backing a resolution that would give architects and builders the right to install polystyrene insulation without flame retardants beneath foundations. Clipboard in hand, she squinted through her purple-framed glasses at the panelists and said that using these chemicals in insulation doesn’t improve fire safety. “This is corroborated in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Spain, where flame-retardant-free insulation has been widely used without incident for as long as 18 years,” she said. Architects, fire and combustion scientists, and a representative from the International Association of Firefighters also spoke in support of the measure. They argued that flame retardants get into human blood and are linked to health problems in firefighters and the general population, and in insulation they don’t even seem to delay blazes.

Then came the Energy Efficient Foam Coalition, the North American Flame Retardant Alliance, and representatives from DuPont and Owens Corning, all saying that newer, polymer-based flame retardants are different. “It’s guilt by association. They are taking all flame retardants and trying to say it’s all bad,” said John O’Connor, a toxicologist with DuPont. As it came time to vote, a panel member who’d been a firefighter became choked up. “We’re losing too many firefighters. We’re losing too many young firefighters,” he said, eyes shining with tears. The council agreed with the industry, rejecting in a 10-to-1 vote the resolution Blum and others were supporting.

And so she has more mountains to climb. Blum is concerned not only about flame retardants in buildings but also that the “bigger is better” logic of polymers will see the retardants applied once again to items such as clothing. Although she acknowledges that polymers are less likely to get into human cells, she says the risk increases when they’re used in close contact with skin. Israel Chemicals Ltd., which has a concession on the Dead Sea and makes about a third of the world’s bromine, has already said in regulatory filings that it’s developed polymeric formulations not only for insulation and circuit board, but for textiles. “Polymers are better, but not completely safe, because they can break down into monomers,” Blum says. “And I never met a brominated monomer that I like.”

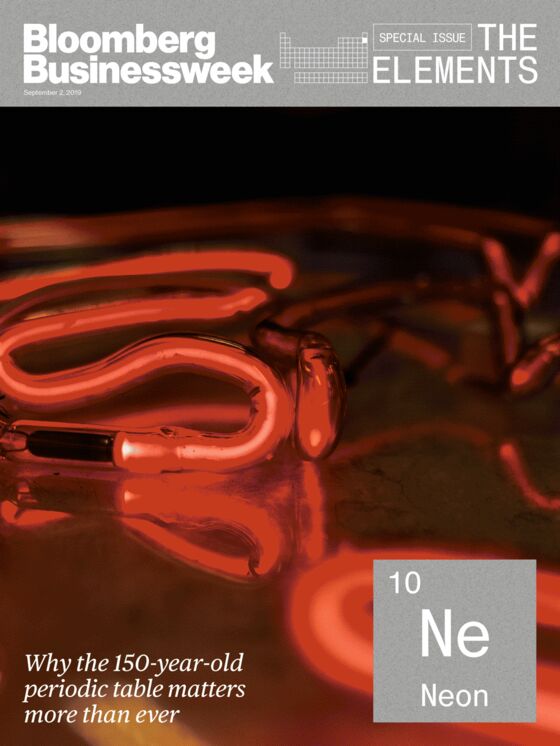

This story is from Bloomberg Businessweek’s special issue The Elements.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Ferrara at dferrara5@bloomberg.net, Jeremy Keehn

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.