Argentina’s Macri and Kirchner Need to Face Each Other If They Hope to Win

Argentina’s Macri and Kirchner Need to Face Each Other If They Hope to Win

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Investors’ worst fears for Argentina were confirmed in late April, when a poll from well-known consulting firm Isonomia showed President Mauricio Macri, the great hope of investors when he was elected in 2015, losing narrowly in a runoff election to populist former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. The price of Argentine bonds plunged, and the country’s chance of default in the next five years rose to 60 percent, from 49 percent a week earlier.

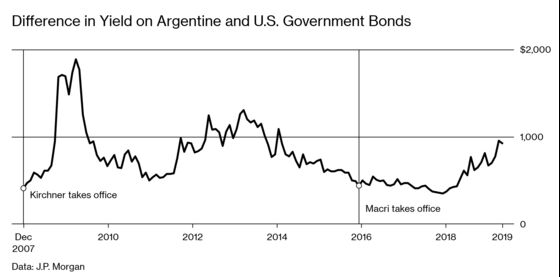

Kirchner and Macri are bitter rivals. She refused to attend his swearing-in ceremony after he defeated her party’s candidate in the 2015 presidential election. He says she ruined the country’s economy and fostered a culture of corruption. Much of Macri’s time in office has been spent trying to rebuild investor confidence after Kirchner refused to negotiate defaulted debt with holdouts. Even so, last year he was forced to go to the International Monetary Fund for a record $56 billion bailout after a combination of high inflation and rising U.S. interest rates soured investors on the Argentine peso, sending the currency into free fall.

Yet with presidential elections coming this year, Macri and Kirchner also need each other. Various polls show them finishing first or second in the initial round of voting, with Roberto Lavagna, a former economic minister who presided over the boom of the mid-2000s, coming in third. Polls also show Macri and Kirchner losing to Lavagna by a wide margin in a two-person runoff. So it appears that the only way one of them can win the presidency is to run against each other.

“In almost any other circumstance, the president of Argentina would face guaranteed defeat,” says Benjamin Gedan, director of the Argentina Project at the Wilson Center in Washington. “In almost any other circumstance, the former president would not have a prayer to return to office. A significant portion of voters for either of those two would be holding their nose while they cast their ballot.”

Macri and Kirchner represent dramatically different approaches to running the nation’s economy. Public spending soared under Kirchner’s administration. She fixed the exchange rate, raised tariffs, and made it illegal for Argentines to exchange pesos for dollars at banks. The IMF censured Kirchner’s government in 2013 for publishing inaccurate inflation and growth data.

Macri was elected in 2015 on pledges to restrain inflation, cut labor costs, reduce social security spending, and end protectionism. He made changes swiftly, lifting currency controls and restoring relations with Europe and the U.S. But by 2018, lingering high deficits and national debt, combined with an emerging-markets sell-off, pushed the currency over a cliff. The IMF bailout forced Macri to speed up deeply unpopular spending cuts, which sent his approval ratings to new lows. If current trends continue, Argentina will have been in recession for three of his four years in office.

“You have the prospect of a free-spending populist returning to Argentina, replacing a pro-market administration that’s undertaken an unprecedented degree of austerity to right Argentina’s ship,” Gedan says. “In any sense of policy and personality, they’re polar opposites.”

Just a year and a half ago, Kirchner didn’t look like a presidential contender. She ran for the Senate while facing multiple corruption probes, finishing a humiliating second as Macri’s party scored sweeping victories. The result still won her a seat in the Senate, which also gave her legal immunity. Last year a newspaper investigation, which led to dozens of arrests, alleged that bribes were delivered to her homes in Buenos Aires while she was in office. Kirchner denies any wrongdoing. “It was quite unthinkable and improbable to see the ex-president in such a competitive position today,” says Lucas Romero, director of Argentine polling firm Synopsis.

Despite the alleged corruption dogging Kirchner and the economic plight weighing on Macri, each has an approval rating of about 30 percent. But it’s early days. The first round of voting isn’t until Oct. 27, and a runoff wouldn’t be until Nov. 24. While Macri has confirmed he’ll run, he hasn’t started campaigning. Kirchner, who’s yet to enter the race formally, is to make her first public appearance of the year on May 9 to celebrate the release of her memoir—and is expected to declare her candidacy—almost a year to the day after Macri sought the IMF lifeline.

The bribery investigation is just one of many factors that could influence voters between now and October. Macri loyalists fear a return to populism greatly increases chances of default and the unwinding of Macri’s pro-market stance and U.S.-friendly foreign policy. Those on Kirchner’s side want to put an end to austerity policies that have failed to stabilize the economy. If she loses, chances rise that she could face jail time.

To win, Macri needs the economy to recover and inflation to cool. He also needs calm markets—another global sell-off that thwarts the peso would doom his reelection bid. Says Romero: “All the anger that a major part of the electorate had with the ex-president once she left office has smoothed over a little by the anger that’s grown with this government.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.