Anti-Asian Atmosphere Chills Chinese Scientists Working in the U.S.

Anti-Asian Atmosphere Chills Chinese Scientists Working in the U.S.

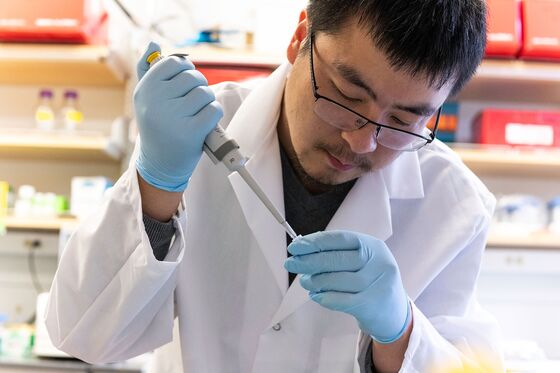

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Nianshuang Wang arrived in the U.S. from China about seven years ago to help explore an obscure niche in structural biology: manipulating coronavirus spike proteins to be more stable and thus better for use in vaccines.

In early 2020 it was Wang who figured out how to make the spike protein on the novel coronavirus bind with human receptors, enabling Moderna Inc. to develop its Covid-19 vaccine in record time. “I thought he’d be perfect to lead our efforts to engineer modified forms of these spikes for use in vaccines,” says Jason McLellan, the University of Texas at Austin professor whose team, including Wang, is credited with the work.

Now Wang, 34, is confronting another kind of contagion. He and his wife have been waiting three years for U.S. green cards, after then-President Donald Trump’s near-halt to legal immigration. Last summer, when the Trump administration closed China’s consulate in Houston amid news reports that the FBI was hunting suspected Chinese vaccine spies in Texas, Wang and his wife explored hiring a lawyer and even considered fleeing the U.S.

They stayed, and no FBI agents came knocking. But Wang says growing anti-Chinese sentiment is palpable, making him and other Chinese scientists increasingly afraid that they’re no longer welcome in the U.S. Several of his Chinese scientist friends have abandoned long-held dreams of pursuing careers in the U.S. and are working in the U.K. and Germany instead, he says.

“The tensions between the two countries have actually made a big difference,” Wang says. “Now the U.S. isn’t so popular among Chinese Ph.D.s.”

An explosion of hate attacks against Asian Americans in the past year has been blamed on the xenophobic rhetoric of former President Trump, particularly his racist broadsides labeling the novel coronavirus the “Chinese virus” and “kung flu.” But other U.S. leaders and institutions have helped inflame the situation, arousing particular suspicion toward people of Chinese descent. The Justice Department’s National Security Division is pursuing suspected economic spies under a heavily publicized program it calls the China Initiative, a name that casts suspicion on 1.2 billion people at a stroke. FBI Director Christopher Wray gives speeches beseeching Americans to take cover from what he calls China’s “whole-of-society” blitz to steal American know-how. And universities and research institutions—such as Houston’s MD Anderson Cancer Center and Atlanta’s Emory University—have been scouring disclosure filings of ethnic Chinese faculty for any failures to divulge research or funding ties to China. Previously unreported cases of alleged disclosure shortfalls have emerged at such supposed bastions of liberal thought as Harvard University and New York University.

The firings and federal prosecutions that have resulted from some of these investigations have damaged the careers of more than a dozen tenured professors, all casualties of what university compliance officers like to call “conflicts of commitment”—a phrase that echoes the Cold War slur “dual loyalties.”

Peter Michelson, a physics professor and senior associate dean for the natural sciences at Stanford University, blames Wray’s “whole-of-society” hyperbole for whipping up anti-Chinese fervor at some companies and campuses, fueling exaggerated mistrust of Chinese graduate students and engineers. “You don’t cast a broad net like that. That’s profiling,” says Michelson, who co-chairs a project of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences to strengthen international science partnerships. “We’re trying to attract talent to this country, but I think some of his rhetoric, while perhaps unintended, puts a target on people’s back. Words do matter.”

Joe Biden is trying to set a different tone on China, saying at a March 25 news conference that “we’re not looking for confrontation,” with Beijing, “although we know there will be steep, steep competition.” He’s embraced a growing chorus of tech executives and policy wonks who argue to U.S. research chiefs that the most urgent need, with respect to China, is to heal thyself. “First, we’re going to invest in American workers and American science,” Biden said at the news conference, where he promised to restore U.S. investment in basic research and science to “closer to” 2% of gross domestic product, the range it was in the 1960s, up from about 0.7% of GDP today.

The challenge is to be a lot smarter and more nuanced than the Trump administration was about which technologies the U.S. must dominate to protect its vital interests, while continuing to attract the brightest minds from China and elsewhere to be the lifeblood of U.S. innovation. “The solution to have more American students pursue STEM studies is magical thinking,” says Peter Cowhey, a former senior trade official in the Clinton and Obama administrations and dean of the School of Global Policy & Strategy at the University of California at San Diego.

To maintain its economic and security edge in the decades to come, the U.S. needs to excel in four core areas, according to a report in November from a team led by Cowhey and published by UC San Diego’s 21st Century China Center and the Asia Society: artificial intelligence, 5G telecommunications, biotechnology, and basic research. A fifth imperative, the design and engineering of semiconductors, is essential to driving advances in the others. Biden’s infrastructure proposal includes $50 billion to subsidize domestic chip research and manufacturing.

Ensuring public and private funding for these strategic priorities, and removing the most sensitive research projects from universities to top-secret government labs, can secure the American research base while sustaining the defining feature of the nation’s innovation success: openness. “The U.S. doesn’t need to be No. 1 in everything,” Cowhey says. “It needs to be strong across the board and the leader in core areas.”

The U.S. needs a small yard with high, well-marked fences, as Cowhey puts it, in contrast to the Trump administration’s paranoid pursuit of Chinese scientists for taking even the most basic research back to China. Clear delineation of nationally protected intellectual property would come as a huge relief to Chinese scientists working in the U.S. “We don’t make foreign students sign a loyalty oath,” says Stanford’s Michelson. “It’s a mistake to build an adversarial relationship with these people.”

Some institutions have resisted the China scare. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology is paying for the legal defense of Gang Chen, a professor of mechanical engineering who was indicted under the China Initiative in January on wire fraud and tax charges for allegedly failing to disclose research funding from China. Chen has pleaded not guilty. After Chen’s arrest, MIT President Rafael Reif issued a statement clarifying something many other schools have avoided admitting: that for years MIT has been integrally involved in the professor’s collaboration with China. In 2018, China’s Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen agreed to pay MIT $25 million over five years to co-create a mechanical engineering institute with centers at both universities, Reif said. While Chen was the institute’s inaugural MIT faculty director, “This is not an individual collaboration; it is a departmental one,” Reif wrote, with $19 million of the Chinese contribution earmarked for collaborative research and education, and $6 million set aside as a gift for MIT to support building renovations and an endowed graduate fellowship

Reif also expressed sympathy and support for MIT’s sizable ethnic Chinese community, haunted today, he wrote, by “a growing atmosphere of mistrust and suspicion.”

California State University, the nation’s largest four-year college system, provides attorneys and moral support to its faculty members facing China Initiative investigations, says Leslie Wong, who was president of San Francisco State University from 2012 to 2019. “To single out a population and then not defend them for the work they’ve been doing tirelessly is so disingenuous,” he says. “I still can’t get my arms around it.”

Elsewhere, it’s a different story. New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine has suspended two professors it accused of failing to disclose research and funding in China, according to four people familiar with the matter. Before any official finding of guilt, school officials have slashed the professors’ salaries, barred them from campus and university computers, and ordered them not to communicate with colleagues, these people said. Such actions constitute an “extraordinary remedy” under NYU’s Faculty Handbook, which says a tenured professor’s suspension is appropriate only when continued employment “threatens substantial harm to himself or herself, to others, or to the welfare of the university.”

John Beckman, NYU’s spokesman, declined to answer questions about individual personnel matters, which he said are confidential. Kent Hirozawa of Gladstein, Reif & Meginniss, the New York law firm that represents the accused professors, says they declined to be interviewed and requested their names not be published pending resolution of the private employment matter.

One of the suspended professors could be among the first NYU faculty members stripped of tenure under a streamlined process that the medical school urgently sought last fall. In December the university’s board of trustees approved the change over objections from the NYU faculty senate’s tenure council, which cited a lack of “compelling explanations and evidence” for superseding the existing tenure revocation process.

The change eliminated protections for NYU medical professors that had been in place for all NYU faculty since the 1980s. Tenured professors had been entitled to a hearing and an appeal before two university-wide faculty committees. But medical school officials argued that the process was too slow; now the school will have its own disciplinary panel, composed of five tenured professors from the medical, nursing, and dental schools. Disciplined faculty members will have only one appeal, directly to the president of NYU.

Beckman says the change in the medical school’s disciplinary procedures wasn’t aimed at speeding up any specific cases. The new process, he says, “still ensures the extensive due process rights for those who are the subject of a disciplinary proceeding that one would expect in an institution in which academic freedom and faculty tenure are core principles.”

Harvard, citing similar allegations of disclosure lapses, began termination procedures against one of its tenured science professors without ever interviewing the person about its allegations, says the individual’s attorney, Peter Zeidenberg of Arent Fox in Washington. Zeidenberg, a former federal prosecutor, represents about two dozen ethnic Chinese researchers ensnared in the China Initiative nationwide. Harvard initiated tenure revocation proceedings and stopped paying the person, all without giving the individual the opportunity to respond to its allegations.

“I would have thought that schools like Harvard and NYU would be less easily intimidated by the government’s strong-armed tactics and would stand up for their professors,” says Zeidenberg, who also represents one of the accused researchers at NYU. “But all too frequently that’s not the case.” Harvard spokesman Jonathan Swain declined to discuss personnel matters.

Rising anti-Asian activity, on city streets and at universities, deters China’s best from coming to the U.S. to study and work, posing a serious danger to the nation’s research base, say some of the most prominent American scientists and academics. Elite U.S. universities that are accustomed to their pick among thousands of brilliant Chinese applicants are losing some of the most coveted prospects to universities in Australia, Canada, and Europe.

“A large fraction of stuff being created in American universities and in industry is actually coming from Chinese immigrants who’ve become citizens here,” Nobel Prize laureate Steven Chu, the former U.S. energy secretary who’s now a Stanford physics professor, said in a September webinar about the China Initiative. “It’s not like we’re shooting ourselves in the foot. I think we’re shooting ourselves pretty close to some important regions in the head.”

Evidence from McLellan’s lab at the University of Texas underscores the point. Last year a Chinese Ph.D. who operated the lab’s electron microscope and who McLellan says was instrumental in providing high-quality data for the vaccine-related breakthrough, moved back to China “out of visa frustrations,” McLellan says.

Wang says he had trouble finding a job in the U.S. last year even after gaining renown in biomedical circles for his work with McLellan. (He and McLellan, among others, hold a key patent related to some of the Covid-19 vaccines, along with Dartmouth College and the National Institutes of Health.) Whenever Wang told prospective employers he didn’t have permanent residency status, the conversation ended quickly, he says. He was finally hired by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., the New York company whose experimental treatment for Covid-19 was given to President Trump. Wang considers himself fortunate, he says.

“It’s increasingly hard for Chinese people to survive here.”

Read next: Wall Street’s Overlooked Minority Is Waiting to Be Heard

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.