Andrew Yang Hopes to Ride His Free-Money Plan to NYC’s City Hall

Andrew Yang Hopes to Ride His Free-Money Plan to NYC’s City Hall

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When Andrew Yang said he was running for mayor of New York City in January, people were thrilled. This spring he’d do something like deliver a speech outside a Brooklyn catering company, and a passing jogger would see him, stop, and jog in place for half an hour just to listen to him talk. He’d be outside a food hall in Hell’s Kitchen when a young woman would approach him and, her voice shaking with nervousness, ask him to sign the back of her cellphone case. On a subway platform, a teenage girl squealed when she saw him, then apologized for being too young to vote.

“Andrew Yang is pretty sick,” Alex Arce, 20, a student at New York University, told me in April. Arce and a friend had happened upon Yang as he stood outside a boarded‑up restaurant in Manhattan’s East Village and called for a full reopening of New York’s bars.

“We need commonsense regulations!” Yang was saying. “I don’t know about you, but I miss sitting next to people in bars!” At the time, less than a third of the city had been fully vaccinated.

I asked Arce why he liked him.

“I don’t know, he’s just a cool guy,” he said.

What about his policies, anything that he stood for?

Arce thought a minute. “The universal income thing?” he finally offered. “That’s pretty great.”

For someone who has never held government office and has campaigned only once before, when he ran for president in 2019, Yang is extraordinarily adept at getting people to like him. Early this year he was bumping elbows with strangers and leaning in close for photos—which may explain how he contracted Covid-19 in February, just weeks into his campaign.

When the weather was still cold he wore the same thing wherever he went: dark overcoat, blue and orange Mets scarf, and a black face mask with “Yang” printed in big white letters, a sort of Where’s Waldo approach to getting his name out there. It’s the same trick he used while running for president, wearing a lapel pin that said “MATH” to the Democratic debates and tying himself to one signature idea: that every American should get a basic income of $12,000 from the government, no strings attached.

Yang dropped out of the presidential race in February 2020, but more than a year later, 85% of New Yorkers still knew who he was and what he stood for.

“I love it! Basic income! Stimulus checks!” said Glen Kelly, outside the Mets’ Citi Field, where Yang was meeting fans before the first home game of the season.

“That income idea,” echoed Ramon Guadalupe, a few days later, when he ran into Yang at the reopening of Coney Island. “I like that he’s for regular people.”

The irony is that under a Yang mayorship, most New Yorkers wouldn’t actually get any money. The concept that made Yang famous, the thing people love him for, isn’t something he’s proposing for New York. He can’t—the city couldn’t afford it. Instead, he’s running on “ cash relief,” a payment one-sixth the size of his presidential proposal, targeting only the poorest 6% of New Yorkers.

“I want to be the antipoverty mayor,” Yang told me. “I’m very excited about it.” He led in the polls for months after he entered the race, and although he’s recently been slipping, he could still win the Democratic primary on June 22 under the city’s new ranked-choice voting system. If he does—and presumably goes on to win the general election in the heavily Democratic city—his plan would, as his campaign flyers proudly proclaim, make New York City the site of “the largest basic income program in history.”

The question is, would it be enough?

Andrew Yang is easy to talk to. There’s something familiar about him, something that makes people want to be his friend. When he speaks, his remarks come peppered with bursts of self-conscious laughter, a sort of guttural huh-huh-huh that erupts whenever he says something too personal or serious or that he thinks the other person might not like. In the two months I followed him around New York, he was almost always in a good mood—“Tell me more! Tell me more!” he once giddily exclaimed as a grocer in Queens explained the difference between city and state dining regulations—except for a few times when it was very obvious he was not.

Yang grew up a slightly nerdy kid, the son of Taiwanese immigrants, in mostly White suburban neighborhoods in Schenectady and Westchester County. He played Dungeons & Dragons and Atari and did well enough in school to both skip a grade and get a scholarship to the prestigious Phillips Exeter Academy. From there it was on to Brown University, Columbia Law School, then the corporate law firm Davis Polk & Wardwell, where it took only a few months for Yang to discover he didn’t want to be a lawyer after all. “They’d sit you at a desk and say, ‘Here are a bunch of documents. Go,’ ” Yang says. “I said, ‘OK, that is not what I want.’ ”

He was looking for something else to do when a friend he’d made at the firm, Jonathan Philips, came to him with an idea: What if, instead of wasting money on black-tie galas, a charity could hold an online auction for almost nothing, freeing it up to put more money toward its actual cause?

“Andrew immediately perked up,” Philips says. “I remember his eyes just lit up. He’s a problem solver, and he very much wanted to solve this problem.” The two men quit their jobs and launched a company, Stargiving, an online platform for auctioning off celebrity meet-and-greets.

It didn’t work. For one thing, they didn’t know any celebrities. Also, the first dot-com bubble had just burst. “It failed miserably,” Yang says. “I will never forget how that felt.”

He spent the next few years hopping between jobs. He was in his early 20s and had $100,000 in student loan debt. He couldn’t afford rent in New York, so he slept on friends’ couches and ate a lot of free bread samples at the sandwich chain Così. For extra money he became the first instructor at a small GMAT test-prep company called Manhattan Prep.

Yang got the job because he knew Manhattan Prep’s founder, Zeke Vanderhoek. In 2006, Vanderhoek left to start a charter school; he asked Yang to replace him as chief executive officer. Soon after that, Yang met his wife, Evelyn. “Things really clicked into place for a number of years,” he says. “They were, I think, some of the happiest years of my life.” He ran Manhattan Prep for about five years, taking it from $2 million in revenue to more than $17 million. In 2009 he sold the company to Kaplan Inc., a deal that earned him several million dollars, but stayed on as president.

Over time, though, a problem began to nag at him. The Great Recession had just happened, and yet here were all these college kids taking out massive loans for an MBA, even though there wouldn’t be many jobs available when they graduated. At the same time, Yang was touring colleges across the U.S., visiting parts of the Midwest and South he’d never seen before. He was shocked at how economically depressed the regions were. He wondered if he could figure out a way to get college graduates to work in Middle America, boosting local economies.

Yang left Manhattan Prep in 2011 to start his attempt at a solution: Venture for America, a nonprofit modeled on Teach for America that would place college graduates at startups in cities such as Detroit and New Orleans. VFA fellows, as they were called, would get work experience and maybe go on to found companies of their own.

Yang launched VFA with the ambitious goal of creating 100,000 jobs in smaller U.S. cities by 2025. The nonprofit was immediately popular; Tony Hsieh, the late e-commerce entrepreneur, donated $1 million so VFA could help revitalize his hometown of Las Vegas. President Barack Obama named Yang one of his “Champions of Change” before the first class of VFA fellows had even been placed in their cities.

“The fundamental problem that VFA was trying to solve wasn’t something most people were talking about,” says Ethan Carlson, a former VFA fellow who graduated from Yale and was matched with a tech company in Providence. “By pointing it out and saying, ‘I’ve designed a solution for it,’ it felt very compelling. Of course, the real story is much messier than that.”

VFA never achieved what Yang wanted it to, at least not on the scale he envisioned. The economic forces that had hollowed out the middle of the country were too big, too intractable, to be fixed by plopping a few hundred Ivy League graduates in Cleveland. Earlier this year the New York Times reported that only 150 people work at companies started by VFA fellows in their original cities. The Yang campaign disputes this figure; it says VFA created 4,000 jobs, though not necessarily in smaller cities. When contacted by Bloomberg Businessweek, Venture for America said it no longer tracks job creation as a metric of its success.

VFA’s shortcomings bothered Yang. In 2016 he was driving across northwest Michigan, passing through small towns with boarded-up storefronts, when he stopped at a diner to eat. “I just thought, ‘How am I talking about entrepreneurship?’ ” Yang says. “The scale of need for changes to the economy is so massive, it gave me a sense of how hollowed out communities really were.”

He started reading books about job loss and automation. He fretted about the growing number of working-age adults receiving disability payments in lieu of a job. But it was Raising the Floor, written by Andy Stern, the former head of the Service Employees International Union, that pushed Yang into politics.

In his book, Stern argued that a $12,000 universal basic income could help offset the wage stagnation and job loss so many Americans faced. He called for a “huge public awareness advertising campaign” for the idea and said the best way to do that was for someone to run for president. Yang liked the book so much that he went to hear Stern talk and, when the event was over, asked him to lunch.

“He said, ‘I’m going to make you an honest man. You said someone should run for president in 2020 on basic income, and I’m going to do that,’ ” Stern recalls.

“Andy was like, ‘Who are you again?’ ” Yang says.

The idea behind basic income is simple: People need money to live, so the government should give it to them. Ideally, a thriving economy allows people to prosper on their own. But there are always some who are left behind. A basic income would ensure that everyone could afford food, shelter, and other necessities, no matter what.

The U.S. has never implemented a national basic income program, though it did come close. In 1969, Richard Nixon included what he called a “guaranteed minimum income” of $500 per adult (about $3,600 today) and $300 per child in his Family Assistance Plan; it passed the House of Representatives twice but died in the Senate and never became a law. A few cities launched pilot programs; the largest, in Denver, ran from 1971 to 1982 and involved 4,800 families. But by the time Ronald Reagan took office in 1980, Washington was looking to curb welfare programs rather than expand them, and the political momentum for a minimum income petered out.

For the next 35 years, it was relegated to a niche idea occasionally floated by academics and policy wonks but rarely taken seriously. “You’d go to these conferences for basic income enthusiasts, and you’d be lucky to get 20 people in a room,” Stern says. “And you’d never see a politician there.” Then, in 2016, two things happened: Chris Hughes, one of the co-founders of Facebook Inc., created the Economic Security Project with the goal of funding what he calls “guaranteed income” programs, and Michael Tubbs, then the 26-year-old mayor of Stockton, Calif., decided to try it in his city.

Hughes and Tubbs were attracted to the idea as a way to alleviate poverty. Tubbs came to it from a practical standpoint—“I grew up poor, I saw how hard my mom worked and still didn’t have enough money to pay the bills”—while for Hughes it felt more like a moral imperative. He looked at wage stagnation; the long decline of the middle class; that the U.S. was home to 40% of the world’s millionaires yet still had the highest poverty level of any developed country. “We have the tools and wealth to eradicate poverty in the United States and stabilize much of the middle class in the process,” Hughes says. “I think there is an ethical responsibility to do that.”

In 2017, Stockton became the first U.S. city to announce a basic income program in almost 40 years. Partially funded by Hughes’s Economic Security Project, 125 people were randomly chosen (given a few parameters) to receive $500 a month. Payments didn’t start until 2019. Giving money to people, it turned out, was more complicated than it looked.

Some recipients didn’t have a bank account, so the money was delivered on debit cards. Many of them were already receiving welfare, usually housing vouchers and food stamps, both of which had income limits. Stockton’s experimenters had to figure out how to give them cash without kicking them off other programs. “The goal wasn’t to remove something they were already receiving,” says Sukhi Samra, director of the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration (SEED). “If you do that, you aren’t benefiting anyone.”

Because the money came on a debit card, researchers could track how it was spent. About half went toward groceries and household supplies. Utilities and auto repairs came next. Then there were little things, small purchases that meant much more than they cost. One parent was able to afford a birthday cake for his child for the first time in years.

The payments also helped people find work. At the start of the program, only 28% of recipients had a full-time job, but by the end of the first year, 40% of them did. Some people bought suits for interviews. One man had been eligible to get his real estate license for more than a year but couldn’t take the test because he couldn’t afford to miss a shift at his hourly job. With an extra $500, he took—and passed—the test.

The Stockton experiment had just gotten under way when Yang ran for president; not many people knew about it yet. But he wasn’t proposing a supplement to existing welfare programs. He envisioned something that could replace the “vast majority” of welfare altogether.

Yang called his version of basic income the Freedom Dividend because the name polled well with conservatives. (Liberals liked the idea no matter what it was called.) It looked an awful lot like what Stern proposed in Raising the Floor: a monthly payment of $1,000 for every American between the ages of 18 and 64, pegged to rise with inflation.

“It will help lighten up the bureaucracy of the 126 welfare programs we currently administer,” Yang explained in a 2019 interview at LibertyCon, a convention for libertarians. As an example, he said that someone could choose between food stamps and the Freedom Dividend, but he stopped short of saying he wanted to eliminate food stamps completely.

This didn’t make a lot of sense. For one thing, according to a 2013 Cato Institute analysis of the maximum amount of welfare available in the U.S., even Mississippi, the state with the paltriest programs, offered $17,000 in potential benefits. Most poor Mississippians were only getting a fraction of that, of course, but Yang wasn’t necessarily offering a better deal.

On top of that, the program was going to cost $1.3 trillion. Yang’s primary method of financing it was to institute a value-added tax similar to those found in Europe. He was, and remains, vehemently against raising income taxes on the wealthiest Americans. “I think an income tax is a poor way, an inefficient way, to generate revenue,” Yang told LibertyCon in 2019, explaining that it penalizes people for working hard and earning money.

But a VAT, like a sales tax, is regressive. Poor people spend almost all of their income on goods and services because they have to, and a VAT would therefore capture a larger portion of their money, which means Yang would essentially be financing the Freedom Dividend by taxing the very people he was trying to help. Rob Hartley, an assistant professor at Columbia’s School of Social Work, analyzed the Freedom Dividend and found that while it would bump many people above the poverty rate, it actually increased the number of children living in deep poverty, because their families would be getting fewer benefits and would be paying more in taxes to finance the program.

This kind of nuance was hard to parse when Yang was running for president. He got enough donations to make the Democratic debate stages, but as a minor candidate he was rarely given time to talk at length. It was only at places like LibertyCon or on Joe Rogan’s podcast that he had time to elaborate beyond his elevator pitch.

In those venues, he took some unusual positions. He said he wanted to appoint a White House psychologist and turn April 15 into a holiday to “make taxes fun.” At one point he told Rogan that he was most concerned about male unemployment figures because “men deal with joblessness very, very poorly,” whereas “women are more adaptable” and can more easily find work.

“Joe put Andrew into another dimension,” says Brian Yang, one of Yang’s lifelong friends (they’re not related) who worked with him at Stargiving and raised money for his presidential run. “The day after he went on the podcast, the donations started pouring in.” Yang raised more than $40 million during his campaign, inspired a #YangGang community on Reddit, and at one point had 3% of voters supporting him, which made him a little less popular than Pete Buttigieg but much more appealing than Amy Klobuchar and Kirsten Gillibrand.

Yang dropped out of the presidential race having achieved his goal: to teach Americans about basic income. He quickly formed a nonprofit called Humanity Forward, through which he planned to further advocate for the idea. “His exposure, his ability to grab people’s attention, his almost single-minded focus on basic income as his major policy proposal took the idea to a completely different level,” Stern says. “A lot of people set the table for basic income. But Andrew served the meal.”

Basic income might have faded into the background again, Yang’s candidacy relegated to a Trivial Pursuit question, if it weren’t for the Covid pandemic. The first lockdown orders came less than a month after he ended his presidential campaign. Huge sectors of the economy were shuttered overnight, pushing millions of Americans out of work. And New York City wasn’t just hit hard—it was gutted. More than 20,000 New Yorkers died from Covid that spring, so overwhelming hospitals that they ran out of places to store the bodies.

The number of payroll jobs in the city dropped almost 14% last year, more than twice the national decline, according to a study by the New School Center for New York City Affairs. Nearly 70% of the newly unemployed were people of color, and two-thirds of them were making less than $40,000 a year. Affluent New Yorkers fared better, of course, but many of them did it somewhere else: More than 330,000 people fled the city during the pandemic. Yang was one of them, moving his family from their Manhattan apartment to their second home outside the city. (“Can you imagine trying to have two kids on virtual school in a two-bedroom apartment, and then trying to do work yourself?” he later asked, essentially describing the living conditions of millions of New Yorkers.)

But he hadn’t given up on basic income—or politics. He stumped for Democratic candidates in Georgia. His nonprofit, Humanity Forward, repositioned itself as a Covid-relief organization, donating $1 million to 1,000 families in the Bronx and lobbying Congress on cash relief for Americans.

Yang doesn’t take credit for the three rounds of stimulus checks Congress ultimately approved, but he does consider it an extension of his original idea. “We’re essentially running a very, very large trial” for basic income, he says, pointing out that while the checks aren’t likely to continue past the pandemic, they are a rare example of the U.S. government giving people cash simply because they needed it.

Yang is cagey about why he decided to run for mayor. New York magazine reported that Bradley Tusk, who ran Michael Bloomberg’s 2009 mayoral campaign and is now a venture capitalist and a political strategist for clients such as AT&T Inc. and Uber Technologies Inc., had been casting about for a candidate who’d be amenable to his business interests and landed on Yang after his first choice fell through. (Michael Bloomberg is the owner of Bloomberg Businessweek’s parent company.) Yang puts it slightly differently. “My team talked to the Tusk team, and then we did an evaluation and figured out what the process would look like and a bunch of other things,” he says, an answer so vague it’s almost nonsensical. Either way, by January he’d returned to the city and announced his candidacy. Tusk Strategies would run his campaign.

Things got goofy almost immediately. Policies touted on his campaign website included luring TikTok stars to the city by letting them live in “hype houses” and throwing “The Biggest Post-Covid Party in the World.” When he delivered the necessary signatures to the Board of Elections to officially get on the ballot, he broke into a song from Rent.

At the beginning, the silliness paid off. “He’s very upbeat and positive, I think that’s resonating with voters,” says Christine Quinn, who ran for mayor in the 2013 Democratic primary but lost to Bill de Blasio. “It’s been such a dark time, I think people want to know things are going to get better.”

Yang knew people saw him as the basic income guy. He also knew that in New York, basic income wouldn’t work.

“My first thoughts were, ‘OK, we can’t do the Freedom Dividend,’ ” he says. Most cities and states are required by law to balance their budgets—something the federal government doesn’t have to do—and the Freedom Dividend would cost more than New York’s entire budget. “So what can we do instead? What’s a realistic commitment?”

He tasked Sasha Ahuja, a social worker and progressive activist who’d joined his campaign as co-manager, and another staff member, Jesse Horwitz, with crafting his official proposal. They settled on $1 billion, about one-tenth of New York’s projected 2022 budget. If they divided it up into average payments of $2,000, they could reach about half a million New Yorkers. Their goal is to bump “every New Yorker up to within 50%” of the city’s poverty threshold, Horwitz says. Homeless people, undocumented residents, and the formerly incarcerated would all qualify.

Getting money to people in these groups isn’t easy, though. Many of them don’t have bank accounts; Stockton got around this with debit cards, but Yang wanted to create what he called the People’s Bank, a city-run system through which New Yorkers could use a municipal ID card to open an account and access their payments.

And how would the city find the 500,000 recipients? Ahuja says they’d work with agencies such as the Human Resources Administration, which administers many existing programs, to figure out who gets money and how much. But that’s about as specific as she can get.

Then there was the question of how the money would interact with other welfare programs. “I only talked to them once, and it was to reemphasize to them that this has to be supplemental to existing benefits,” says Samra, who designed Stockton’s experiment. They took her advice; Yang’s cash-relief proposal will supplement state and federal welfare. This is a major ideological shift from his original Freedom Dividend, but Yang insists it isn’t a big deal to him.

“I know that people took me as being very anti-helping-people with the current safety nets, but really I’m anti-bureaucracy more than anything else,” he says. “I think targeted cash relief to alleviate extreme poverty is great! I’m very excited about it.”

Once Yang and his team settled on a plan, they had to figure out how to fund it. This is where things get hazy. Yang says some of the money will come from private donations, but he won’t say how much or from whom. “I’ve talked to various individuals and philanthropists that led me to believe that we could have more resources,” he says. The $1 billion figure is just what he expects the city to pay.

New York is home to 112 billionaires and an additional 7,700 people who have at least $30 million, but Yang still eschews raising income taxes, which for millionaires are already the highest in the country; a hike would require the state government anyway. Instead he’d target vacant commercial property, which is currently taxed below its assessed value. Early in his candidacy he also suggested that the city raise money by putting a casino on Governors Island—that is, until he learned it was prohibited by a federal deed. Then he floated the idea of eliminating tax breaks offered to places like Madison Square Garden, though, again, the state is in charge of that.

Yang assured me he could find $1 billion somewhere. “Am I confident that I’m going to find all sorts of things in the budget where I’m like, ‘I could get rid of this and no one would notice?’ ” he asks. “Like spending $3 million on a city bathroom when you could get the same bathroom for $1 million?”

He estimates it will take as long as two years before his cash-relief program is up and running, mostly because he has to create the People’s Bank first. So it will be a while before anyone benefits. And while 500,000 recipients sounds like a lot, that’s still less than 6% of New Yorkers. By the city’s own estimate it entered the pandemic with 41% of its population at risk of falling into poverty—and that was considered a good thing, because the figure used to be even higher.

To reach 500,000 people, Yang’s offerings have to be relatively small. An average payment of $2,000 a year works out to just $167 a month. That’s a third of what residents got in Stockton. In a city with one of the highest costs of living in the country, $2,000 is practically nothing. Yang’s cash-relief plan is essentially offering the equivalent of a monthly MetroCard for the subway plus an extra $40.

Hartley, the Columbia professor, points out that the people Yang is targeting have so little money that even a seemingly negligible amount can improve their lives. “For some people it doubles their disposable income. That’s substantial. That means something,” he says. A recent analysis of Census Bureau studies showed that the federal stimulus checks, which provided as much as $3,200 per person, helped people buy food and pay their bills during the pandemic, reflecting just how close to the bone millions of Americans live.

Surprisingly, New York has tried something similar before. In 2007 the city launched what it called a “cash transfer” pilot program for 4,800 low-income families, who received about $2,900 a year for three years. It wasn’t a basic income, because the cash was conditional; parents had to “earn” money by participating in job-training programs, for example. “In hindsight it was a huge headache,” says Kristin Morse, then the executive director of the NYC Center for Economic Opportunity, which oversaw the program. “But families did earn the money. They spent it on food and rent and electric bills. In that sense it was a success. But giving people $2,000 or $3,000, you’re not lifting huge numbers of New Yorkers above the poverty line.”

This is the harsh reality of basic income. Giving money to people who need it really does work, but to do it on a grand scale is almost prohibitively expensive, especially for a city. “No city in the United States can afford a guaranteed income for its residents without support from other levels of government,” says the Economic Security Project’s Hughes. “Even with the fuzziest of fuzzy math, it still requires an economic investment at the state or federal level. I think it would be better for people if we’re clear about that.”

That’s not to say a cash-relief program isn’t worthwhile, or that it wouldn’t work, just that the vast majority of New Yorkers won’t notice its effect. Just as Venture for America was a noble but ineffectual answer to a struggling Middle America, so is cash relief a small gesture, one that gnaws away at the edges of poverty but doesn’t come close to solving the deep, intractable inequities that cause it to endure.

Yang knows this. “Is a billion dollars enough? No,” he admits. His cash-relief program needs to operate in tandem with other efforts. That’s why he wants to equip homeless shelters with broadband internet so the children in them can do better in school; expand mental health services and inpatient psychiatric beds to reduce street homelessness; and give a $1,000 annual voucher to families with children who are living in poverty, are English language learners, or have a disability that requires specialized instruction.

But these are all small programs, one-off ideas that are unlikely to be enough, and Yang seems reluctant to make the kind of sweeping changes necessary to really be the “anti-poverty candidate,” as he calls himself. New York’s public school system is one of the most racially segregated in the country and serves 100,000 kids who are homeless. Although the city uses a weighted model that drives more money to schools with lots of low-income students, most of them aren’t fully funded according to what the formula says they deserve. But Yang rarely talks about desegregation. “An extra $1,000 is important and good,” Morse says, “but if families aren’t getting their kids’ needs addressed by the public education system, $1,000 isn’t going to fix it.”

Basic income has a life beyond Andrew Yang. Tubbs is no longer mayor of Stockton, but before he left office he created Mayors for a Guaranteed Income, a coalition of leaders interested in re-creating Stockton’s experiment in their own cities. Samra is now director of MGI, helping municipalities design their own programs. “We’re doing this to feed into one comprehensive agenda to make the case why this should be policy at the federal level,” Samra says. “It’s expensive, but budgets are just lists of a government’s priorities. If you can’t make a financial commitment to the most vulnerable communities, that’s a moral problem. Not an economic one.”

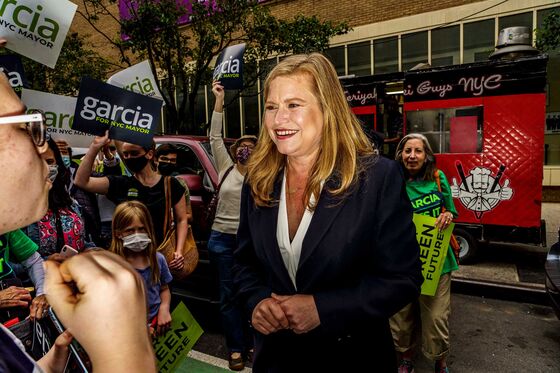

In fact, the idea is so popular that some of Yang’s opponents have proposals of their own. His rival, Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, wants to do it through the earned income tax credit, raising the city’s contribution in a plan that he says would cover 900,000 New Yorkers and get them $3,000 a year. Kathryn Garcia, the former head of the city’s sanitation department, proposes free day care for babies and toddlers whose parents make less than $70,000 a year. That’s certainly not basic income. But private day care costs close to $2,000 a month in New York; she’d be saving even some middle-class parents more than $10,000 a year.

Garcia’s campaign is the polar opposite of Yang’s. She can be awkward and stilted in speeches; she’s never been, and probably never will be, a Reddit meme. But she knows what levers to pull to make the city’s slow, bureaucratic machine come to life. Yang admires her so much that he said he wanted to hire her, until she began to eclipse him in polls.

Yang is not an expert on the mechanics of how the city operates, and as the mayoral campaign has intensified, he’s increasingly seemed out of his depth. Speaking at a virtual forum dedicated to homelessness in May, he suggested the city should create shelters for victims of domestic violence, prompting the event’s moderator to point out that they already exist. At a press conference he’d called to discuss police reform, he appeared unfamiliar with a recently repealed law that had shielded officers’ disciplinary records from public view.

Maybe Yang was just having an off day at the homelessness forum. Maybe his mind went blank when asked about the records law. Mistakes happen. But that doesn’t explain the press conference he held in late May outside the headquarters of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which oversees New York’s subway, bus, and regional rail systems. Yang announced that as mayor he’d wrest control of the MTA away from the state, but he couldn’t articulate how.

“The plan is to take the case to Albany and the people of New York,” he said. “The plan is to ask for mayoral control.” The MTA is a complex network of different transportation systems that collectively employ 75,000 workers and have an operating budget of $17 billion. It’s also one of the largest issuers of municipal debt in the country. When pressed for more specifics, Yang deferred to his policy adviser, who said details weren’t important. “It doesn’t make a lot of sense to ask Andrew Yang or me or anybody else out here exactly how they’re going to unwind the financing structure,” said Jamie Rubin, the former director of operations for New York state.

When the press conference ended, Yang looked deflated. He knew it hadn’t gone well. Hecklers had started to disrupt some of his events; a few days after the MTA debacle, I’d witness a woman call him names as he tried to eat his lunch.

Yang came in fourth in one June poll, behind Adams, Garcia, and progressive civil rights attorney Maya Wiley. But the city’s new ranked-choice voting system—in which the least popular candidates are eliminated and their votes reallocated to supporters’ second-choice candidates—means that if enough New Yorkers pick him second, he could win. Not because of anything he promises to do or not do as mayor, but because of what he represents.

“I met him a couple years ago when he was running for president. He really impressed me,” Jenny Kam, one of the NYU students I met back in April, told me. She liked Yang’s cash-relief plan fine, she said, but disagreed with a lot of his other positions, and as an Asian-American woman she was unimpressed by his plan to combat the rise in hate crimes with yet another police task force.

But she still liked him. He seemed honest and kind, and you couldn’t say that about most politicians. “I think he could be something really great,” she said. “Or he could turn into something disastrous.”

There was only one way to find out.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.