Amtrak CEO Has a Plan for Profitability, and You Won’t Like It

Amtrak CEO Has No Love Lost for Dining Cars, Long-Haul Routes

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- My journey from New York to New Orleans on the Amtrak Crescent began forebodingly. I was stowing my bags in the sleeping car. As the train left the station, the Amtrak attendant who’d be taking care of me on the trip stopped by. “Settle in,” he advised. “We’re going to be here for a while.”

“Yeah,” I said. “Thirty hours.”

“All that,” he replied knowingly, “and maybe more.”

The Crescent is one of Amtrak’s tardiest trains. Southbound, it leaves New York’s Pennsylvania Station every day at 2:15 p.m. Around 9 the next morning it pulls into Atlanta, where many passengers either depart or step off for a long-awaited cigarette. It ambles through some hypnotically beautiful Alabama countryside and somnolent Mississippi towns before arriving in New Orleans, according to the schedule, at 7:32 p.m. Almost three-quarters of the time, however, the Crescent is late, often by two hours or more. Last year, Amtrak lost $39 million on the line, which comes as no surprise. How many people want to take such an unreliable train?

The people I spoke with in the dining car all had stories about the Crescent’s delays and why they endured them. A semiretired cotton company executive from Montgomery, Ala., was a train lover and just happy to be aboard. “I enjoy it,” he said, “even when it’s late.” We ate dinner with an Atlanta dentist returning from a wedding in New York. Normally he would have flown, but he’d had knee surgery and couldn’t sit still for several hours on a plane.

I had breakfast the next morning with David and Sarah, Long Islanders in their mid-20s. David was terrified of flying. “It’s a completely irrational fear, but I stand by it,” he said. Sarah once waited eight hours for the Crescent to leave New York, but she’d grown up taking long trips on Amtrak and enjoyed their quirky moments. Before the meal was over, a congenial dining room attendant named Claude Mitchell led us all in a rendition of “Happy Train Ride to You,” dedicated to a 4-year-old taking her maiden rail excursion with her grandparents. We wouldn’t have done that on a plane.

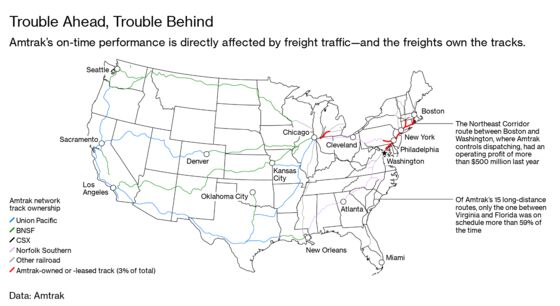

If you wanted to create a railroad from scratch, you’d never design one like Amtrak. It had 32 million riders last year and revenue of $3.2 billion. But it had an adjusted operating loss of $171 million and has needed federal subsidies to stay afloat every year since Congress created it in 1971. The most functional piece of Amtrak is the 457-mile Northeast Corridor between Boston and Washington. The trains on this line may not be as fleet as the bullets of Europe and Japan, but they run frequently and pretty much on time. Amtrak can make sure of that because it owns almost all the Northeast Corridor track and controls much of the dispatching on it, which helps explain why the corridor had 12 million riders last year and an operating profit of $524 million.

Then there’s the rest of Amtrak’s 21,400-mile network. Do you want to catch Amtrak in Cleveland? There’s no train leaving there before 1:54 a.m. or after 5:50 a.m. Bring something to read, because outside the Northeast Corridor, Amtrak’s long-distance trains operated according to schedule only 43% of the time last year.

The biggest reason is that Amtrak owns hardly any of these tracks. For the most part, they belong to freight railroads, whose predecessors persuaded Congress to form Amtrak in 1971 to take over their failing passenger operations. In return for what was essentially a bailout, the freights agreed to give Amtrak preference on their tracks. The meaning of preference is technical and somewhat disputed, but in essence freight trains are supposed to pull onto a siding so trains like the Crescent can get by. In practice, the freights, which control the dispatching on their rails, often keep Amtrak trains idling while their own slower-moving trains pass.

The Federal Railroad Administration and Amtrak want to sort this out by establishing performance standards designed to ensure that the trains are on time more frequently. The freights have resisted. Ian Jefferies, president of the Association of American Railroads, the freight industry’s chief trade organization, recently told Congress that the private railroads carry far more cargo then they did in 1971, and that it’s unreasonable to expect them to pull over every time an Amtrak train comes along. (Paradoxically, Amtrak is also an association member.) For Amtrak, that intransigence—or what it calls flouting of the law—has been devastating. Ridership on its 15 long-distance routes declined last year by 4%, to 4.5 million trips. The $543 million operating loss eclipsed the Northeast Corridor’s profits.

For decades, Congress largely sidestepped the question of how to improve Amtrak, preferring to squabble about whether Amtrak should even exist. But these days, Amtrak enjoys strong bipartisan support. The Trump administration has proposed significantly defunding Amtrak, but Congress has defied the White House. This year it lavished Amtrak with almost $2 billion in annual subsidies.

Amtrak’s board of directors also broke with tradition. In 2017, rather than recruiting from the public-transit sphere, it hired a chief executive officer from the private sector: Richard Anderson, who’d become CEO of Delta Air Lines Inc. after it emerged from bankruptcy and restored it to profitability.

Working without a salary or an annual bonus—he probably doesn’t need the money, having left Delta with $72 million in company stock—Anderson is determined to move Amtrak toward self-sustainability. He’s vigorously cutting costs and vows it will break even on an operating basis next year. That, he says, will enable Amtrak to spend its annual congressional subsidies to buy new trains and fix up its tracks and stations. Anderson will need all the money he can get. The Northeast Corridor has been underfunded for decades and needs an estimated $41 billion to keep its bridges and tunnels, some of which were built more than a century ago, from collapsing.

He also wants to reconfigure Amtrak’s long-distance routes so they’re no longer money sops. He says several, including the Empire Builder and the California Zephyr, which transport passengers from Chicago to the Pacific Northwest and Northern California, respectively, could be turned into luxe excursions for rail enthusiasts who want to cross the Continental Divide in style. Others, he argues, should be broken up into shorter, faster routes between cities, enabling travelers to bypass congested highways and airports with their time-sucking security requirements. Amtrak already operates 28 such routes in states like Virginia and California. These state-supported lines lost $91 million in 2018, but they accounted for 15 million passenger trips—almost half of Amtrak’s total ridership.

Anderson has upset an impressive number of people. Amtrak’s employee unions have condemned his trimming of call-center and onboard service positions and demanded his ouster. U.S. senators from rural states worry that if he gets his way, their constituents will lose service, paltry as it may be. Meanwhile, rail enthusiasts, of which there are more than a few, denounce him as a philistine who wants to kill Amtrak’s long-distance routes, many of which have rich histories, because he doesn’t understand or love trains as they do.

Jim Mathews, president of the Rail Passengers Association, a national advocacy organization for train travelers, sees an irony. “He was brought in to make Amtrak operate as if it were a profit-making company,” Mathews says. “He looked everybody in the eye and said, ‘OK, are you guys ready for this? We’re going to break some stuff.’ And everyone said, ‘Yes, this is what we want.’ And then he started breaking stuff. And people were like, ‘Wait, hold up. Stop! What?’ ”

Tall, bespectacled, and balding, Anderson has a senior faculty member’s cerebral air. On an August afternoon, he sits at an oval table in Amtrak’s headquarters near Washington’s Union Station, dressed casually in a light blue checked shirt, blue pants, and gray sneakers. He’s irritated by his detractors, but only mildly so. “Most of the critics are the people who yearn for the halcyon days of long-distance transportation,” he says, referring to an era when fedora-wearing travelers crossed the country in plush trains, sipping martinis, perusing the funny pages, and visiting the onboard barber if they needed a trim.

Anderson has no such nostalgia, which is odd considering his family background. He grew up in Texas, the son of an office worker at the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway. His dad took Richard and the family on rail trips to Chicago and Los Angeles. “I didn’t come away with some huge love for trains, just like I don’t have some huge love for airplanes,” he says. “They’re machines that you build a business around.”

He got a law degree and in 1978 became an assistant prosecutor in Houston. “He was one of our best trial lawyers,” recalls Bert Graham, Anderson’s boss at the time. “He had a way of seeing through bullshit.” After nine years, Anderson took a job as an attorney at Continental Airlines. In 2001 he alighted to Northwest Airlines, where he became CEO. Following a stint in the health-care business, he returned to the airline world to be CEO of Delta in 2007. Anderson told reporters he hadn’t been recruited to merge the airline with Northwest and then proceeded to do exactly that. He shaved $2 billion in costs.

He also threw an occasional elbow. Anderson campaigned unsuccessfully to get the Obama administration to restrict the access of Delta’s Persian Gulf rivals to the American market because he thought they were unfairly subsidized by their governments. While reciting his grievances in a 2015 CNN interview, Anderson told viewers to remember what happened in September 2001. Many in the aviation industry were stunned. Qatar Airways CEO Akbar Al Baker said Anderson had “no dignity.” Anderson says he was being a fierce advocate for Delta just as he’s trying to be one for Amtrak now.

By the time he departed in triumph in 2016, Delta was routinely ranked No. 1 in the industry for on-time arrivals and fewest canceled flights. Anderson told everybody he was returning to Galveston, Texas, to do some fishing. If so, it didn’t take. He soon got a call from Charles “Wick” Moorman, a veteran railroad CEO who’d signed up to serve as Amtrak’s chief executive for a year and help it find a long-term successor. He spent six months as Moorman’s co-CEO before taking over in January 2018.

Anderson has taken on the freights as no previous Amtrak CEO did. Last year, Amtrak began publishing an annual Host Railroad Report Card, which grades the six largest private railroads according to how often their trains delayed Amtrak’s on long-distance and state-supported routes. Canadian Pacific Railway got an A; Norfolk Southern Corp., which owns the tracks south of Washington on which the Crescent operates, received an F. (A Norfolk Southern spokeswoman said in an email that the company “takes seriously its obligations to Amtrak and does its best to support freight and passenger operations.”) Sarah Feinberg, former head of the Federal Railroad Administration during the Obama presidency, applauds Anderson’s harder line. “The reality is the freights have been holding up Amtrak trains forever,” she says. “Previous Amtrak CEOs should have done the same.”

Anderson has cut costs at Amtrak with the same zeal he showed at Delta. He shuttered a 550-employee call center in Riverside, Calif. Amtrak already had one in Philadelphia, he said, and didn’t need another when so many customers were booking trips online. He was just as unsparing with management positions, getting rid of 600 and filling some of the top slots with former Delta and Northwest executives.

Perhaps inevitably, he and his team have introduced ideas from the airline industry, including assigned seating in the first-class section of the Northeast Corridor’s Acela. Kevin Mitchell, chairman of the Business Travel Coalition, says the move infuriates corporate executives and their colleagues who board in different cities, hoping to sit together to discuss their affairs. “It was absolutely crazy,” Mitchell says. “It didn’t work.” Amtrak disputes this, saying customers like assigned seats and it’s part of the reason revenue on the Acela’s first-class cars has risen 11% this year.

Anderson also demonstrated his lack of sentimentality toward trains. Early on, he visited Washington’s Union Station, and he was appalled. The Marco Polo, former President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s private Pullman car, was sitting on one of the station’s prime tracks. “Everybody’s emotionally attached to it because it was FDR’s personal car,” he says, still sounding annoyed. “Fine, go put it in a museum. But let’s not block up Union Station with some old antique car.” The car has been moved.

For train lovers, the moment of truth was when Anderson initially refused to put up funds to improve a 400-mile stretch of the Southwest Chief between Dodge City, Kan., and Albuquerque. Anderson said it would be more prudent to run a bus between the two cities instead. “The idea that Amtrak would think about replacing passenger service with bus service for 400 miles and believe that we would still have a long distance passenger train service is something I can’t get over,” Senator Jerry Moran, a Kansas Republican, scolded Anderson in a hearing in June.

The Senate ordered Amtrak to run the train and forget about buses. Fine, says Anderson, but he hasn’t given up on his plans to segment some routes.

The heresies have continued. In April 2018, Amtrak said it was eliminating traditional dining-car service on overnight trains on two routes east of the Mississippi. For decades, part of the ritual for sleeping-car passengers was strolling to the dining car for surf and turf, prepared to order by a chef. Now they’re getting something closer to airline treatment: ready-to-serve meals heated for them on the train.

M.E. Singer, a contributor to Railway Age, a trade publication, says this is an old trick the Southern Pacific employed to depress ridership in advance of abandoning its passenger lines in the 1960s. “First, they took off the diners,” Singer says. “Then they took off the sleepers. Then they extended the schedules. This is all very deliberate.” Singer, it should be noted, is a train lover’s train lover. He sent me a list of the summer rail vacations he’s taken, starting in 1957 with a two-night trek from Chicago to Yellowstone National Park on the Union Pacific’s National Parks Special. “If I close my eyes,” Singer wrote, “I can still offer a vivid description of travel on each train.”

One of the more thoughtful critics of Anderson’s plans is Knox Ross, a former mayor of Pelahatchie, Miss. He’s also a member of the Southern Rail Commission, which was created by Congress more than three decades ago to extend passenger train service in the region. In the afternoon of my second day on the Crescent, Ross boarded the train in Meridian, Miss., and joined me in the lounge car. Wearing a blue suit and looking somewhat like a heftier John C. Reilly, he was sweating a bit from the August heat.

It was good to ride the Crescent with Ross. He’d spent a lot of time on the train and knows the crew well; his company made the trip more tolerable as it became clear we weren’t going to reach New Orleans on time. Throughout the day, the Crescent had been passing freight trains laden with cement, gravel, new cars, and oil. But then the trains started being pulled to the side so Norfolk Southern’s trains could pass.

Ross has been working with Amtrak to create a corridor between New Orleans and Mobile, Ala. These cities were once served by Amtrak’s Sunset Limited, which ran between Los Angeles and Orlando. But the tracks between New Orleans and Florida were washed out 14 years ago by Hurricane Katrina. Amtrak never reinstated service on that section, even after CSX Corp., the owner of the tracks, resumed freight service. The proposed New Orleans-to-Mobile route fits perfectly into Anderson’s new strategy, and this summer it seemed as if it were finally under way. Senator Roger Wicker, a Mississippi Republican, announced that the FRA had awarded a $33 million grant for infrastructure improvements along the line. The states of Louisiana and Mississippi pledged a total $25 million in matching funds. But Alabama Governor Kay Ivey, also a Republican, refused to put up the state’s $2.2 million contribution, saying it didn’t have “the luxury of providing financial support for passenger rail service.”

Then there’s CSX. “They haven’t agreed to anything,” Ross says. “They don’t want the train.” (CSX says it’s up to Amtrak to decide what to do.) With such obstacles, Ross doesn’t see how Anderson’s corridor plan can be extended nationally. Nor does he think Anderson’s confrontational tactics are improving things with the freights. “I’ve talked to some of those people,” he says. “They hate this report card.”

As the train idled near Ellisville, Miss., we walked through the coaches. In the lounge car, Ross asked a conductor, “So how far in the hole are we now?” The man looked up from his paperwork. “It’s 5:13 p.m.,” he said. “We’re already 2 hours and 10 minutes late.”

By the time of my trip, it was clear Amtrak was planning to get rid of dining-car service on the Crescent, too. Ross didn’t think that would help fill seats. And what of the crew members who might lose their jobs, including Claude Mitchell, the singing dining-car attendant? Exuberantly friendly whether he’s serving food or having a casual conversation, Mitchell recognized Ross and took the opportunity to say hello. “Oh, hey, how are you doing?” Ross said, brightening up.

“Always a pleasure,” Mitchell said, gripping his hand.

“We’ve ridden quite a few trains together,” Ross said. “Hopefully, we’ll have a little side trip one to Mobile that you can work.”

“I’m ready,” Mitchell said.

“You can sing a tune all day over there.”

“Well, he’s heard me sing,” said Mitchell, nodding my way. “I was a little hoarse, but I love doing it. I just hope and pray that we keep going.”

“We’re going to try,” Ross said.

I try to get Anderson to take a train ride, but it never happens. Instead, we talk again in Washington. He says nobody’s been fired as a result of his cost-cutting, including the dining-car changes on the Crescent. Everybody gets to keep their job at Amtrak, he says, though it may not be exactly the same one and in the same ZIP code. I later find out Mitchell is now a sleeping-car attendant on the Crescent; hopefully, he’s exercising his vocal talents there.

I ask Anderson about what Ross said about his plan for shorter routes. He reels off some trends in his favor. Highways are too packed. Much of America’s population growth is expected to be in cities, where young people aren’t buying cars. “There are going to be obstacles,” Anderson says, “but these obstacles are going to be overwhelmed by population, demographics, and road congestion.”

The one time he starts to lose his cool—and only a little—is when I ask if he’s trying to kill the long-distance routes, as some say. Anderson says Amtrak isn’t just continuing to operate the routes as Congress has ordered, it’s improving them. He notes that Amtrak will spend $75 million next year refurbishing the cars on routes like the Crescent and an additional $40 million on new locomotives. “Part of the problem is that the people that are the big supporters of long distance are all emotional about it,” he says. “This is not an emotionally based decision. They should be reading our financials.”

Anderson says he plans to ask Congress next year, as part of Amtrak’s regular five-year reauthorization process, to allow it to begin experimenting with shorter routes on some lines. He’s considering the Sunset Limited, which operates three days a week between Los Angeles and New Orleans. It was late more than half the time last year and lost $35 million.

As for the freights, Anderson says he’s hopeful they won’t be delaying Amtrak’s trains much longer. In June the Association of American Railroads lost its long-running legal battle to prevent the FRA and Amtrak from establishing on-time performance goals.

Kathryn Kirmayer, general counsel for the AAR, says there’s still much for Amtrak and the freights to haggle over, including the meaning of preference on the freight tracks. “Some suggest that ‘preference’ should mean treatment like a presidential motorcade, where everything stops and pulls to the side to allow a single car—or in this case, train—to pass,” she wrote in an email. “That approach just doesn’t work.” Anderson doesn’t sound worried. He’s also asked Congress to give Amtrak the right to sue the private railroads if they hold up its trains.

In November, Anderson announced Amtrak’s latest financial results. Ridership had risen 800,000, to a record 32.5 million passenger trips in fiscal 2019. The financial loss had narrowed to $30 million from the previous year’s $171 million, meaning Amtrak was well on its way to an operating profit in 2020.

Recently, Anderson floated yet another unsentimental idea: Perhaps the long-term future of Amtrak in some parts of rural America won’t be trains at all. “It would have to be driverless vans,” he said at a travel conference. “Smaller driverless vans.”

Read more: A Private Equity Firm Wants to Build a Train to Las Vegas

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Ferrara at dferrara5@bloomberg.net, Silvia Killingsworth

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.