The Super League Debacle Forced Manchester United’s American Owners to Listen to Fans

The Super League Debacle Forced Manchester United’s American Owners to Listen to Fans

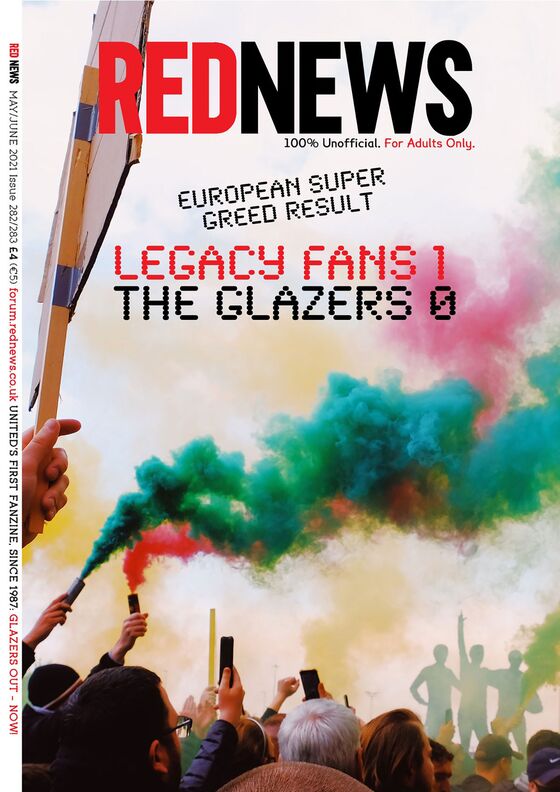

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Several weeks ahead of the U.K.’s scheduled release from pandemic lockdown, Manchester United fans returned to Old Trafford arena in a hail of smoke bombs. A crowd of protesters had gathered outside in early May, demanding that United’s American owners, the Glazer family, sell the team. Then about 100 fans broke into the stadium, whose stands had been empty for the entire Covid-disrupted season. Smoke filled the air. A young fan in faded jeans and a white hoodie marched down the sideline, holding a corner flag aloft like an enemy banner claimed in battle. Others chanted a familiar refrain: “Love United, hate Glazer!”

The Glazers were among the first in a wave of overseas billionaires to invest heavily in English soccer, shifting the sport’s center of power away from locals. Hardcore United fans have despised the family since Malcolm Glazer took over in 2005, in a deal that left the club with hundreds of millions of dollars in debt. When Malcolm’s sons Avram, Bryan, and Joel toured Old Trafford after the takeover, they had to be extracted in a police vehicle as protesters hurled bricks.

May’s unrest grew out of a public-relations disaster. Two weeks before the protest, the Glazers and a group of soccer’s richest owners had made a stunning announcement: Their teams, which included most of the perennial favorites from the English, Italian, and Spanish leagues, were preparing to break away from the existing structures of European competition. The Super League they proposed would likely commandeer the bulk of the sport’s TV revenue, potentially leaving national leagues in tatters. Soccer officials and fans of both Super League and non-Super League clubs were outraged. U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson threatened to block the proposal with a “legislative bomb.” Within days the plan collapsed, and the owners publicly apologized.

After staving off the Super League, English fans are now trying to wrest back some of the influence they’ve lost to overseas investors. They argue that sports teams are fundamentally different from ordinary businesses—that they should operate as something akin to a public trust, with input from the local community. The pitch invasion at Old Trafford, which led to a series of arrests and forced the Premier League to reschedule a high-profile match between United and Liverpool, has helped spur a push for reform. The protest “was very organic,” says Barney Chilton, editor of the United fanzine Red News. “Suddenly these kids went in. Kids of the fathers and mums who support United and were so appalled 16 years ago said, ‘Well, sod it.’ ”

Over the summer, Joel Glazer, United’s co-chairman, met with fans over Zoom, the first time he’d spoken directly with them. The club has also been locked in negotiations with a leading fan coalition, the Manchester United Supporters Trust, over a new corporate structure that would allow fans to claim a financial stake in the club. On the call, Joel said he was aiming to create “the largest fan ownership group in world sport.” A similar process of corporate reconciliation is unfolding at several other English clubs that had planned to join the Super League.

The push is backed by Parliament. For Johnson and other government officials with populist pretensions, fan representation is an easy sell; in November a Conservative-led parliamentary task force released a report calling for legislation to give fan groups more authority. “If you own a football club, you’re running a cultural asset,” says Damian Collins, a Conservative member of Parliament. “The fans want more representation on the board, they want to know what’s going on, and they want a sense that the rules are properly enforced.”

The anti-Glazer protests in Manchester started to dissipate in late summer, after the club opened the season strongly and brought back Portuguese forward Cristiano Ronaldo, a former United star. In recent months, however, the team has suffered some embarrassing defeats, prompting club executives to fire the coach. At the same time, the negotiations over fan ownership have dragged into the winter. Many supporters suspect the Glazers are trying to generate positive PR before launching a second, less ham-fisted attempt at a Super League.

The financial discussions with United have been led by Duncan Drasdo, a former chemist who dropped out of a doctoral program to focus on fan politics. Drasdo, now chair of the Manchester United Supporters Trust, is sometimes criticized by fans who claim he’s being manipulated by the Glazers. But he professes to have no illusions about the family’s ultimate objectives. “They want to use the club for their own benefit,” he says. “You’ve got this real challenge: People want to be loyal to their football club, but they know you are being loyal to something that is exploiting you.”

Barney Chilton started Red News in the late 1980s, when he was a soccer-mad teenager. The fanzine soon caught the attention of Alex Ferguson, who was early in what would become a 27-year tenure of near-constant success as United’s coach. In 1989, Ferguson sent Chilton a typewritten letter in response to a series of scathing articles about the team, which was going through a rough patch. “You have the best interests of the club at heart,” he wrote. “I’m sure your interests are the same as mine.” Chilton keeps the letter in his office, a reminder of a time when the club felt more like a community institution than a multinational behemoth.

United has occupied a central place in English soccer for most of its history. Founded by railway workers in the 1870s, the club, originally known as Newton Heath, was once a bastion of Manchester’s working class. The team became a powerhouse in the 1950s and ’60s, under Scottish coach Matt Busby, who built a squad full of homegrown talent. But as the soccer industry started looking outward, so did United. It was listed on the London Stock Exchange in the early 1990s, and not long after, it joined a group of clubs that broke away from English soccer’s governing body to establish the Premier League. In the new league, the top teams could share TV revenue among themselves rather than distributing the funds to clubs in lower divisions.

National leagues like the Premiership are the core of European soccer. Every team plays against its domestic rivals, and the top clubs qualify for the Champions League, an annual 32-team tournament the Super League would have effectively replaced. In some ways the Premier League’s formation laid the groundwork for the Super League, helping the biggest teams spend lavishly on salaries and stadium upgrades while smaller clubs struggled to stay solvent. Despite United’s role in that shift, the team maintained its local roots throughout the 1990s. Fans could own shares, which parents would bequeath to their children.

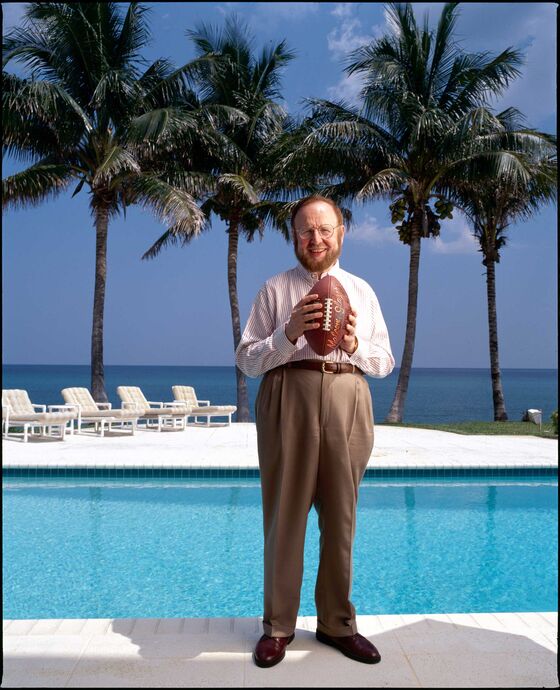

The Glazers bought United at another turning point in English soccer history, as ultrawealthy foreign owners took over clubs, drawn in by lucrative TV deals and sponsorship opportunities. The splashiest of them was Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich, who bought Chelsea in 2003 and started spending vast sums on new players. The same year, Malcolm Glazer, who’d built a real estate empire in the U.S. and owned the NFL’s Tampa Bay Buccaneers, took a major stake in United. In 2005 he persuaded two of the club’s largest shareholders to sell, then took the company private in a leveraged buyout, borrowing more than $900 million from banks and hedge funds.

To many United fans, this was the original sin. Abramovich’s spending had brought Chelsea consecutive Premier League titles. The Glazer takeover, by contrast, saddled United with debt and turned it from a public company into a private corporation run by secretive Americans. The sale felt like “a death in the family,” Chilton says.

Hardcore fans were divided over how to fight back. Some were content to chant “Glazers out!” from the stands, while others canceled their season tickets. The debates got ugly. “There are people I haven’t seen since,” says Ian Stirling, vice chair of the Manchester United Supporters Trust. “It split up friends who had been going to games for years and years.” One group of fans founded a new club, F.C. United of Manchester, which competes in a semipro league six divisions below the Premiership.

After buying United, Malcolm delegated management responsibilities to Avram, Bryan, and Joel. Protests could erupt at the most inopportune moment. A few years after the takeover, Bryan met a woman for dinner at an Indian restaurant in Manchester, according to Mike Halligan, a security guard for the Glazers in the 2000s. When they emerged afterward, “F--- Off Glazer” was written in red sauce on the hood of his car. Bryan wasn’t pleased. “He comes out with her, sees this, and becomes quite sort of aggressive,” Halligan says. “It was quite amusing.”

The Glazers seemed to have what Halligan describes as a passing interest in soccer. When they sat in their box at Old Trafford during home matches, they sometimes struck him as distracted or uninterested, discussing business dealings in Tampa as the game unfolded in front of them. Once, on a trip to see United play in Wales, Malcolm’s son Edward told Halligan he’d rather stay at his hotel than face angry United supporters at the stadium. (The Glazers declined to comment on Halligan’s recollections.)

In the early years of the Glazers’ ownership, United continued to succeed on the pitch, winning a string of Premier League titles under Ferguson’s leadership and securing its third Champions League crown in 2008. Despite that run of success, fan protests intensified in 2010, sparked by the release of financial data that showed the club’s debt had grown since the buyout. Instead of sporting red and black at matches, fans started attending in green and gold, the colors of the club’s original incarnation, Newton Heath. A group of wealthy fans calling themselves the Red Knights launched an unsuccessful effort to buy the club. And at the end of a Champions League match at Old Trafford, David Beckham, a United hero who’d recently joined the Italian club AC Milan, donned a green-and-gold scarf, a major publicity coup.

By most accounts, this wave of activism hardly bothered the Glazers. “Won’t it blow over?” Joel asked a PR employee, Tehsin Nayani, after Beckham was photographed wearing the scarf, according to an account of the exchange in Nayani’s book, The Glazer Gatekeeper. “It’s always blown over in the past.” It more or less did. In 2012 the club was floated on the New York Stock Exchange, and its annual revenue continued to climb. By 2019, the last pre-pandemic year, the figure had reached about $830 million, almost triple what it was when the Glazers took over.

Despite fans’ dire predictions, the family has spent lavishly in the transfer market. But the team hasn’t come close to winning a domestic league championship since its victory in 2013, the year Ferguson retired. Meanwhile, local rival Manchester City, financed by a Middle Eastern oil tycoon, has won a fistful of trophies. United fans blame the club’s failures on the hundreds of millions of dollars in interest payments the Glazers have made to their creditors and on the dividends the family has collected—approximately $24 million a year, according to soccer finance expert Kieran Maguire. The money would be better spent, fans argue, on player salaries or improvements to Old Trafford, where they’ve complained about a leaky roof and other deteriorating facilities.

“To let it rust is just appalling,” says Chilton, who’s regularly attended home games since the ’80s. “It still gives you goosebumps entering that theater. But it’s rotting.”

The vitriol of the Manchester United fan base has long mystified the Glazers’ friends and colleagues in the U.S., where the family is known primarily for its unglamorous lifestyle and stubborn commitment to privacy. Malcolm, who died in 2014, lived modestly for a billionaire; his only indulgence was a red Corvette he drove around Florida. “They’re whatever the opposite of ostentatious is,” says Marc Ganis, a sports consultant who’s known the family for decades. “They are family people first.”

They weren’t always so cleanly aligned. When the Glazers bought United, angry fans scoured Malcolm’s biography for evidence of perfidy, fixating at times on a decades-old financial dispute over his mother’s estate. When she died in 1980, Hannah Glazer left an inheritance of about $1 million. But her four daughters were convinced that she’d actually been worth more—and that Malcolm was concealing her assets. They battled in court for more than a decade.

At one point early in the dispute, the siblings met at a hotel in Rochester, N.Y., where a family friend had agreed to mediate the dispute, according to someone close to the family who requested anonymity to discuss a sensitive matter. A settlement seemed within reach. Then, late one evening, Malcolm got a call from one of the sisters. She unleashed a stream of invective, the person close to the family says, calling him “selfish.” Malcolm responded that he would never settle. As the proceedings wore on, one of the sisters complained that his presence at depositions was “psychologically intimidating,” according to legal records. During a deposition in the mid-’80s, Malcolm interrupted to accuse two of the sisters of communicating in code—through their knitting.

He was equally aggressive in his real estate dealings. One of his early projects involved a parcel of land in Rochester he bought from a local family. When he’d approached the owners, he later said in a deposition, he’d assured them he intended to move an aging relative onto the property. His actual plan, he admitted, was to open a trailer park.

Malcolm was eager to involve his six children in the family business; he brought them along to meetings when they were young, telling them to listen and soak everything up. When Joel was in his mid-20s, he and his older brother Bryan spearheaded a deal to buy the Buccaneers for $192 million; Malcolm’s other three sons, Kevin, Avram, and Edward, also became co-owners, along with his only daughter, Darcie. Malcolm acknowledged knowing almost nothing about football, but his sons loved the sport. “He said he bought the team for the boys,” says Sandra Freedman, the mayor of Tampa in the mid-’90s. “They’d always wanted a football team.”

The Glazers are much more popular in Tampa than in Manchester. When the family took over, the Bucs were one of the worst teams in the NFL, and some fans feared the franchise would relocate. The Glazers kept the team in Florida, changed its colors from a garish orange to a stylish red and pewter, and opened a new stadium. The Bucs won their first Super Bowl in 2003 and their second in 2021.

People who’ve worked with the Glazers say the family generally functions as a unit, making important decisions collectively. In their early years running United, Bryan, Joel, and Avram seemed intent on maintaining tight control from the U.S., according to a person who requested anonymity to speak candidly about the club’s operations; the brothers would call senior staff late at night, the person says, inquiring about the performance of top executives.

Since Malcolm’s death, Joel has emerged as the family’s public face, especially in England. A United fan since college, he’d become interested in owning the club in the late ’90s, after he saw a headline in the Wall Street Journal about a takeover attempt by Rupert Murdoch. Now Joel is the main point of contact between United’s senior leadership and the family, and he was supposed to serve as one of the leaders of the Super League, alongside the president of Real Madrid. Joel was heavily involved in planning the project, according to a person with inside knowledge of the process, working closely with John Henry, the American billionaire who owns Liverpool as well as the Boston Red Sox. In a series of private meetings, the person says, Joel argued that English clubs would never maximize TV revenue within the existing Champions League format. But he also seemed intent on protecting some of the sport’s traditions, speaking reverently about the FA Cup, a 150-year-old single-elimination tournament in England.

Joel and the other owners wanted the top European clubs to play each other more often; under their proposal, the founding Super League teams would have automatic slots while everyone else would compete for the few remaining places. But the owners badly underestimated fans’ commitment to the semi-egalitarian ideals of modern soccer, in which even the richest teams can miss out on the Champions League after a disappointing season. UEFA’s president called the owners “snakes” who were “spitting in the face of football lovers.”

As fans protested in April, Joel joined the other owners on a conference call to devise a response, according to people familiar with the planning who requested anonymity discussing internal matters. But soon the owners were ready to abandon the project. After a PR team secured a slot in a major U.K. newspaper for an op-ed defending the Super League, none of the clubs agreed to sign it.

These days, Joel runs United from the 10th floor of an office building in Bethesda, Md., around the corner from a Bloomingdale’s. He hasn’t granted an in-depth interview since the Glazers bought the club in 2005. In September, a Bloomberg Businessweek reporter met with him for two hours in a conference room at the office, where he reclined in a red swivel chair emblazoned with United’s crest. Outside, the lobby was decorated with photographs from the club’s glory years: Ryan Giggs scoring a famous goal against Arsenal, Ole Gunnar Solskjaer celebrating on the night United won the Champions League in 1999.

The conversation was off the record, but Joel later agreed to answer a short list of questions over email. Shortly before publication, however, he changed his mind, declining to offer any comment on the record. He also declined, on behalf of the Glazers, to respond to the accounts of people who’ve worked with the family, including Halligan, their former bodyguard.

A United spokesman, Charlie Brooks, provided a statement defending the Glazers’ leadership of the club, noting that they haven’t increased season ticket prices for 10 years and plan to upgrade Old Trafford. “The Glazer family are totally engaged, committed long-term owners and fans of Manchester United,” Brooks wrote. “The owners have provided a financial stability that ensures the club can consistently compete in the transfer market and attract the world’s best players.”

In June, Joel appeared via Zoom at a gathering of the Manchester United Fans’ Forum, a group of supporter representatives who convene a few times a year at meetings supervised by the club’s staff. He defended his family’s financial management of United, emphasizing that the dividend payments are only a “modest proportion” of revenue and that the club’s debt has gone down in recent years. But he acknowledged that the Glazers should have communicated more with fans. “I can’t change what’s happened in the past. I can only work to change the future,” he said. “The club is for the fans, it’s what it’s all about. And without the input and the discussion with fans, it makes decision-making all the more difficult.”

Exactly how much power the Glazers are willing to give up is unclear. In December, United unveiled a new fan advisory board, which will meet four times a year with senior executives to provide input on the club’s commercial decisions. But the panel will be purely advisory, with no voting power, according to a club official. And the negotiations over a share sale to fans have proven complicated. Over the summer, United agreed to let fans purchase a class of stock that carries the same voting rights as the Glazers’ stock. The fans want United to make an unlimited number of those shares available, creating a path to an ownership coalition with significant decision-making power. The discussions have stretched for months, with no end in sight. “The ball’s in their court,” says Drasdo of the Manchester United Supporters Trust. “It’s up to them whether they feel they can accommodate what we think is necessary.” (United said in a statement on its website last month that it’s working with the trust to navigate the “significant legal and regulatory complexities” of a share sale.)

One factor that could influence the discussions is government intervention. The parliamentary task force was led by Tracey Crouch, a Conservative legislator and an avid Tottenham Hotspur fan. The report she released in November called for local fans to control a “golden share” of their teams—essentially a veto over certain key governance decisions, such as plans to sell the stadium or enter a new competition. Under a golden-share system, the report said, “a future European Super League would not be possible without fan consent.” For now, the report’s recommendations are simply guidance for future legislation, and club owners will almost certainly lobby to block aggressive new rules.

In the months since the Super League collapsed, soccer fans in England have debated a range of alternate governance models. One popular option is known as 50+1, after a rule in German soccer requiring that supporters own a majority share of voting rights in every pro club. In the Bundesliga, clubs are run as member associations in which fans hold sway over ticket pricing and vote to approve the appointment of top executives. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the fan-appointed leaders of the two most successful German teams, Bayern Munich and Borussia Dortmund, refused to join the Super League.

Even German fans acknowledge the approach has its drawbacks, however. By deterring foreign investors from pouring money into German soccer, the model has made it harder for teams to compete for talent with other top European clubs. “It would be fair if every country had it,” says Daniel Erd, a sports lawyer at Pinsent Masons who’s based in Germany. “But it’s tough for German teams right now, being the only ones.” (The exception is Bayern, which has won two Champions League titles in the past decade.)

There’s no realistic path to a 50+1 model in England. But the prospect of legislative action appears to have made clubs there more receptive to change. Over the summer Tottenham, one of the Super League clubs, announced it would give fan representatives a seat on its seven-member board. The only catch: The team hadn’t actually consulted any fans about the plan. “We heard about it when they announced it in public on their website,” says Martin Cloake, who runs the Tottenham Hotspur Supporters’ Trust.

Cloake suggested an alternative: a separate board made up of elected fan representatives, with certain golden-share veto powers. He submitted a detailed proposal compiled by a group of Spurs fans, some of them corporate consultants. Tottenham is set to hold talks with the fans in the coming weeks, according to a club spokesman.

The English clubs involved in the Super League have vowed the idea is dead. But some of its other proponents have refused to back down, and many fans remain concerned that the big-time Premier League owners will eventually regroup and try again. Even with outside help, supporter groups often feel outmatched when they walk into boardrooms full of billionaire investors and highly paid lawyers.

Most fan advocates are volunteers; their activism is a labor of love and amateur accounting. Ever since the Glazers took over United, Chilton has been teaching himself the rules of finance, struggling with the nuances of dividend calculations and payment-in-kind loans. For the fanzine, he’s published stories by accountants, hoping to raise awareness about the club’s debt and the size of the Glazers’ dividend checks. “Some people just want to watch football,” he says. “I wish I could be like that.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.