Washington Hasn’t Learned the Real Lesson of the China Shock

Washington Hasn’t Learned the Real Lesson of the China Shock

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- If there’s one area of bipartisan consensus to be found in Washington these days, it’s China policy. Everyone, whether Democrat or Republican, is a China hawk, no matter how much they may differ about everything else, from mask mandates to the causes of inflation.

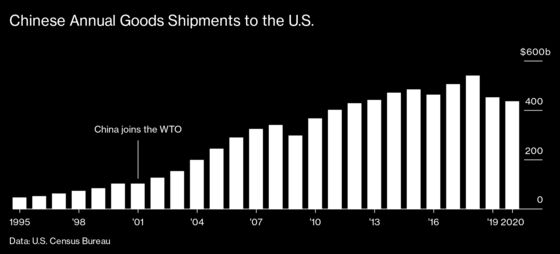

It’s a remarkable change from 20 years ago, when a healthy majority in Washington supported China’s Dec. 11, 2001, accession into the World Trade Organization. And one major and well-documented reason for the shift is the work of economists David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson. Since 2013 they’ve been detailing the dislocation in the U.S. economy caused by a surge in imports from China, which had led to a loss of as many as 2.4 million jobs by 2011.

What’s now known as the China shock has been linked to falling incomes in once-buzzing factory towns, political disaffection and the rise of Donald Trump, the dwindling marriage prospects of working men, the opioid crisis, and what economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton have called “deaths of despair.”

In a working paper published in October, Autor, Dorn, and Hanson documented how, while the China shock actually peaked in 2010, it was still being felt as recently as 2019. Their report came with another sobering message: American policymakers haven’t learned the right lessons from one of the most significant chapters in recent economic history. And that matters. Because there are more shocks coming.

The economists in their latest paper endorse the view that for the U.S. economy as a whole, China’s rise has actually been beneficial. Apple Inc.’s successes with the iPhone wouldn’t have been possible without Foxconn’s sprawling manufacturing facilities in China, they point out. The problem is the job losses were concentrated intensely in places such as North Carolina’s furniture belt and factory towns in the Midwest— and the policies meant to help those places recover were too timid. Which is why the economic and political consequences have endured.

Put another way, the China shock wasn’t only, or really, a failure of trade policy. It was above all a failure of domestic economic policy. There may be a new bipartisan consensus on what’s usually framed as the need to “get tough with China.” But, as Autor, Dorn, and Hanson wrote, “despite these now well-documented adverse labor market impacts of globalization, there is no consensus about how to remediate such injuries.”

Autor, Dorn, and Hanson argue that well-funded, targeted government policies could have helped prevent the economic blight that engulfed many affected communities. But everything from unemployment benefits to job retraining programs were “too small in scale” and “too limited in scope,” says Hanson, who’s on the faculty at Harvard Kennedy School. “We just weren’t nearly generous enough.”

One thing we’ve learned from the pandemic is that the U.S. is better at fighting a sudden crisis than a slow, grinding one. Washington spent trillions of dollars to blunt the economic pain from the Covid-19 recession, but the rescue effort was improvised and therefore more chaotic than it needed to be. European countries, in contrast, were able to fall back on long-standing programs, such as work sharing, that allowed workers to remain on company payrolls even while factories were idled or restaurants shuttered.

Certain American idiosyncrasies—including an overreliance on local taxes to fund schools and police departments—actually amplify the impact of economic shocks. When industry departs an area, local authorities often roll out fresh tax breaks to attract new employers. Communities then become trapped in a vicious cycle in which the tax base erodes, leading to cutbacks in public services and investment that cause families to pick up and move elsewhere. “We let places go to seed in a way that other countries don’t,” says Autor, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The paper is pointedly critical of the tools the Trump administration deployed in the name of making some of these places great again: “The favored solution of populist politicians to regional distress is to raise import barriers and block immigration.” Trump’s tariffs on imports from China harmed a lot of consumers and businesses, as other economists have documented, without creating a meaningful increase in jobs. When President Joe Biden leaves those tariffs in place, he’s just doing more of the same. “The idea that we can just tariff our way to prosperity is ludicrous,” Autor says.

Autor also disapproves of Trump’s decision to pull the U.S. out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the 12-nation trade agreement that the Obama administration negotiated. The TPP was built largely with an eye on securing America’s place in the Pacific and gaining leverage on China, which isn’t a party to the deal. It established tighter controls on state-owned enterprises and new rules for things like data flows that would have benefited American workers, Autor—along with Dorn and Hanson—argue. That Biden, like most in Washington, sees joining the TPP as too politically toxic only perpetuates the error.

Revisiting the lessons from America’s inadequate response to the China shock may help policymakers make better choices when the next cataclysm strikes. At least that’s what Autor, Dorn, and Hanson hope.

As Hanson wrote in Foreign Affairs earlier this year, the energy transition from fossil fuels to renewables is sure to bring another round of concentrated economic pain with its own consequences. For every new electric vehicle battery plant that opens, there’s a combustion engine factory that’s doomed to close. One community wins while another loses.

Although Biden’s “Build Back Better” plan includes some spending for regions likely to be affected, there isn’t nearly enough, Hanson argues. “The regionally concentrated joblessness” that hit the U.S. with China’s ascension “is one of the great tragedies of the last 25 years,” he says. And neither party has a platform “that confronts the possible expansion of that tragedy due to the energy transition.”

Other shocks loom: robots and automation, another pandemic, and perhaps even a second China shock. Beijing has ambitions to become a dominant player in industries such as artificial intelligence, EVs, and semiconductors and is backing those up with billions of dollars in investment. Washington in response has embraced an industrial policy of its own, starting with subsidies for the construction of domestic chip plants.

But dealing with economic shocks isn’t just about confronting geopolitical competition. It’s about making sure your own citizens are protected from the effects of change. It’s about having unemployment benefits that capture everybody equally, housing people can afford, and schools that can adapt to train a new generation of workers. Twenty years after China joined the WTO and the shock accelerated, it’s still not clear that those embracing Washington’s new political consensus on China get that.

Read next: End Trump’s Trade War? Easy Inflation Win Could Backfire on Biden

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.