The Slip-and-Fall King Wants to Save You From Your Next Wipeout

The Slip-and-Fall King Wants to Save You From Your Next Wipeout

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On April 22, 2011, not long before she planned to marry, Amber Morris walked into a Costco in St. Louis where a puddle was waiting. In the store, Morris slipped and hit her right knee so hard on the floor that she dislocated her kneecap. Her fiancé helped her up and took a photo of the slick of rotisserie chicken grease coating the floor where she’d fallen. Two weeks later, Morris went in for emergency surgery and never came out. A blood clot in her heart killed her at age 39. Her burial took place on what was to have been her wedding day.

Morris’s parents filed a wrongful death suit against Costco Wholesale Corp. and hired a St. Louis law firm that called itself the “winningest” on billboard ads. That firm recruited an expert witness named Russell Kendzior, a former flooring salesman from Texas who over the past quarter century has been retained in more than 1,000 lawsuits and styles himself as America’s most prominent floor safety advocate. Kendzior was prepared to argue not only that the chicken grease was evidence of negligence but also that the store’s flooring was inherently dangerous. In 2015, Costco, which declined to comment for this story, settled for an undisclosed sum, according to Kendzior.

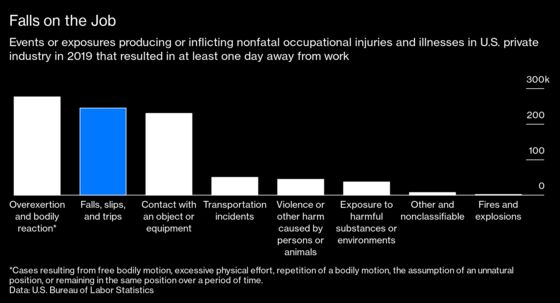

The millions paid out annually in settlements are compounded by the $50 billion that Americans spend on health care annually to treat slips, trips, and falls. In a typical year, bad spills kill thousands and seriously injure hundreds of thousands, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than a quarter of the 888,220 injuries resulting in days away from work in 2019 were caused by slips, trips, and falls, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. It’s common to refer to these cases broadly as accidents, but Kendzior says that’s a misnomer. “Accidents are not predictable and not preventable,” he says. “Most slips and falls are not accidents. They’re incidents.”

Kendzior and other safety advocates argue that a huge part of the problem, one in urgent need of reform, is the lack of mandatory testing and labeling for tile, vinyl, and other commercial flooring materials. Friction is what experts use to gauge slipperiness, measuring the wear and resistance between two objects, such as a shoe rubbing against a floor. But there are no mandatory federal or industrywide friction standards for flooring or other walkway surfaces—only voluntary guidelines, some of them mutually exclusive. Even the industry’s own standards find floor safety wanting. In a 2017 report by CNA Financial Corp., one of America’s largest insurers, half of all U.S. commercial flooring failed to measure up to an industry standard supported by ceramic tile manufacturers.

Across the multibillion-dollar commercial flooring industry, definitive numbers can be tough to come by. Yet the frequency of personal injury claims at major retail chains, which include falls, underscores advocates’ concerns. Data from Bloomberg Law show that over the past year, Costco was named in more than 200 personal injury lawsuits, while Walmart Inc. appeared in an average of three every day, which accounted for 60% of all new litigation filed against it. Kendzior says a single big-box store received 200 claims worth an estimated $3 million during one particular six-month span. Publix Super Markets Inc. reported roughly 69,000 falls across its 925 stores over five years in a 2012 affidavit provided by the company’s in-house legal assistant in a slip-and-fall case in Florida. None of these companies responded to requests for comment.

Why aren’t retailers and other commercial businesses taking this problem seriously enough to solve it? Two reasons, Kendzior says: First, the costs are generally passed on to the companies’ insurers. And second, ageism. While plenty of working-age people like Morris take devastating falls every year, most cases involve the elderly. “We live in a society where youth is glorified,” he says. “And being old is, you know, put them in a nursing home and let them die.”

Over the past decade, as Kendzior’s voice has grown louder in Washington, an ecosystem of floor safety entrepreneurs has emerged. These teams, who test ways to prevent robot feet from sliding on tile and other materials, broadly agree that clear standards are needed when it comes to how slippery a floor can be. They disagree, however, on what those standards should be, and even how to assess them. A tribometer, the primary instrument used to measure friction, can be calibrated differently from manufacturer to manufacturer and return wildly different results.

The firms often have competing motivations, and many have a vested interest in trash-talking the others. There are the researchers for such trade groups as the Resilient Floor Covering Institute, which represents makers of vinyl, cork, and laminate surfaces. The Tile Council of North America represents, well, tile. There are franchises like Walkway Management Group Inc.; consultants who also sell tribometers; and other firms that offer to test surfaces and certify products. They often work directly with the flooring companies.

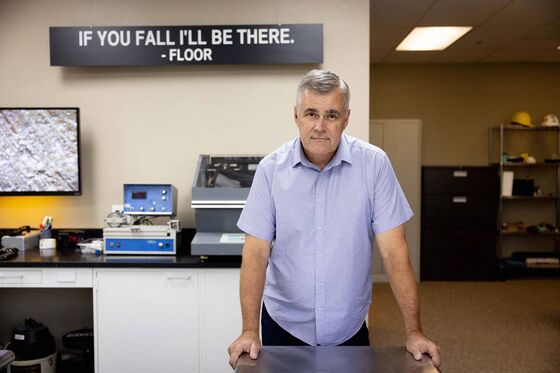

Then there’s Kendzior, who’s built a one-man consulting firm called Traction Experts Inc. around his witness testimony; a small company called MAD Safety Instruments that distributes tribometers; and a nonprofit, the National Floor Safety Institute (NFSI), which is trying to make his the federal standard. The only thing most of the other organizations agree with him on is that U.S. flooring materials need better labeling (like letter grades) so people know how slippery they can get. Some of the trade groups don’t even agree with that.

Kendzior’s critics, many of them competitors, accuse him of fearmongering and paying short shrift to the actual science in favor of his own mythos and profits. Admittedly, the guy makes $500 an hour from a line of work often dismissed as ambulance chasing, and he has a lot of interlocking side hustles, plus a penchant for grandiosity. “I changed the world,” he says. “I didn’t mean to, but I did, and when you do something that big, you make friends and you make enemies.” By the same token, he works in an industry where a ubiquitous inanimate object can kill you.

His tiny operations’ obsession with flooring, a seemingly dull and largely unregulated field, has antagonized and drawn attention from his rivals as well as the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), where he’s been lobbying for a federal standard for six years. In Washington several of the organizations with their own competing standards have campaigned against his in an effort to dominate.

Among other things, Kendzior has a knack for transforming frictional standards into captivating stories that swing jurors. “It’s a war,” he says, noting his rivals’ own conflict of interest. “I’m protecting people because I believe one day we’re all going to be judged for what we did on this Earth. And I want it to be said I did my best.”

Kendzior, one of five kids raised in the Chicago suburbs by a welder and a factory worker, began his career in the area 35 years ago selling no-wax vinyl flooring, at the time all the rage in Reagan-era kitchens. He worked as a sales rep for a regional distributor of Armstrong Flooring Inc., a Pennsylvania-based company, his first job out of Bradley University in Peoria, Ill., where he majored in math. It wasn’t long before he began hearing about customers’ safety problems. The common refrain, he recalls, was: “We’ve put a lot of floors in our schools or grocery stores, and people are falling.” When he asked management at Armstrong how to handle those questions, he says he was told to refer angry customers to the lawyers. “What kind of customer service is that?” he thought, and he soon resigned in protest. Colleagues gave him a plaque that read: “You F---ing Quitter.” (Armstrong didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

At the time, Kendzior had a 6-month-old daughter and a mortgage, but he saw a business opportunity to make floors less slippery. He started with cleaning solution. U.S. shoppers love shiny floors that smell like lemon or pine, but such scented cleansers with soap often leave behind a slippery film. “Guess what—desert pine is an oil,” he says. “You just put perfume on your floor and you wonder why it’s slippery. Go figure.”

It would be generous to call Kendzior an amateur chemist, but after three years mixing up prototypes and testing them at area stores after midnight while his wife—the family’s sole breadwinner—worked as a marketing manager for Southwest Airlines, his 13th formulation found a buyer: McDonald’s Corp. After franchisees in the Dallas-Fort Worth area became regular customers, he built the business into a cleaning and chemical company called TractionPlus. He formed a partnership with Walmart on a line of slip-resistant shoes, TredSafe, and divested portions of TractionPlus over the course of the 1990s, pocketing enough to retire.

In 1997, Kendzior reached another crossroads when an attorney asked him to testify in a slip-and-fall case, around the same time he created the NFSI. He became a reliable expert witness in tandem with his development of new friction standards that he used to train others and inform his recommendations for tribometers. After publishing a book with the electrifying title Slip-and-Fall Prevention Made Easy: A Comprehensive Guide to Preventing Accidents, he made his largest splash on the national stage in 2009, when he got his first friction standard published by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI), a nonprofit whose roughly 3.5 million members and 125,000 member businesses coordinate a voluntary consensus system for specifying norms and guidelines in virtually any industry imaginable: fire hydrants, gloves, mayonnaise, shipping containers, or the numeric code assigned to the keys on your keyboard.

Industry trade groups, representing flooring manufacturers with more than $1 billion in annual sales, put forth their own standard. Kendzior’s competitors, too, began to criticize his methods as selfishly motivated or insufficiently scientific. Kendzior, for his part, followed up his first book with two more: Falls Aren’t Funny: America’s Multi-Billion Dollar Slip-and-Fall Crisis and Floored! Real-Life Stories From a Slip and Fall Expert Witness. He also sought federal recognition for his organization’s criteria. Things came to a head in 2018, the second time his NFSI petitioned the Consumer Products Safety Commission to approve its label for national use.

The five commissioners at the CPSC rejected Kendzior’s group’s first bid for a national standard in 2017, citing insufficient data to establish that the NFSI’s benchmark would really help reduce falls. The second time around, Kendzior says, he thought he was better prepared to respond to criticism while staying focused on the inherent danger of flooring products without clear labels.

But over the course of two months, more than 75 letters from flooring trade groups and companies, as well as other forensic consultants and engineers, stated their formal opposition. Many pointed out technical deficiencies and potential conflicts of interest. The Resilient Floor Covering Institute called the NFSI data “irrelevant, unsubstantiated, or misrepresented.” The Tile Council of North America, which introduced an ANSI standard, said Kendzior’s proposal could actually decrease overall safety by giving customers “a false sense of security.” Several others registered the not-unfair critique that the NFSI stood to gain from selling certifications and from sales of an approved tribometer sold by Kendzior’s MAD Safety Instruments.

The commission rejected the NFSI’s proposal along party lines, but not one of the commissioners actually voted for it. The Republicans opposed, the Democrats abstained. Kendzior blames the flooring companies and says his critics are either self-interested industry officials or jealous rivals with financial incentives to support Big Floor. (“These are small people with big egos, and I rained on their parade,” he says. “They’re the losers.”) But he didn’t do himself any favors in his testimony to the commission, during which he accused Acting Chair Ann Marie Buerkle, whom he calls a “right-wing idiot,” of not wanting to enforce safety standards, comparing her to a “hammer that doesn’t want to hit nails.” Even now, he seems to take joy in reliving this act of self-sabotage.

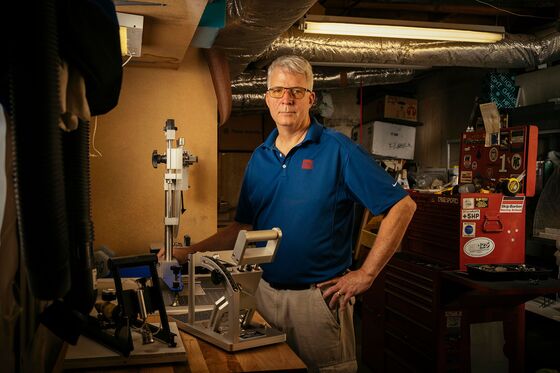

By comparison, the flooring industry’s preferred partner cast himself in the role of good cop. Peter Ermish is an entrepreneur who co-owns Variosystems Group, an international electromechanical company with more than $200 million in U.S. sales. After commercializing designs for a tribometer, he co-founded Walkway Management Group in 2019. Walkway sells the only tribometer currently capable of testing a floor’s compliance with the ANSI standard, and its technology is used to monitor walkway safety in places like the Smithsonian Institute. Ermish was on the board of Kendzior’s nonprofit but has since parted ways, emphasizing what he describes as a more scientifically rigorous approach to preventing falls. Walkway’s head of sales, Rob Vassallo Jr., is less diplomatic, dismissing those paid to spout off their own opinion in court. “Every forensic person is a clown,” he says.

Asked about his own financial interests in consulting with companies to ensure flooring standards, Ermish says safety is his priority and profits are unlikely. “I’m $2 million in the hole,” he says. “We’re approaching breakeven. My dream is to not lose money.” He declined to provide revenue or sales figures.

But their testing to an industry standard, critics contend, only applies to one flooring type: ceramic tiles. Makers of the vinyl and composite tiles found in retail chains, hospitals, airports, and gas stations say that because the standard requires testing floors when wet, and their flooring should never be used when wet, they shouldn’t be judged along those lines. (Good luck telling that to any injured parties.)

If there’s any consensus, it’s that the U.S. needs floor ratings designed for consumers, says John Leffler, who works as a forensic engineer at consulting firm Forcon International in Atlanta. “If I’m an architect or an interior designer, I really need to be able to pull up the Home Depot website and see that this flooring gets an A and this gets a C,” he says. He’s spent years working on a different standard at ASTM International, another standards-developing organization, which was formerly known as the American Society for Testing and Materials.

Coming up with standards, to put it mildly, remains a work in progress. As part of an ongoing collaboration between forensic engineers and the musculoskeletal biomechanics research laboratory at the University of Southern California, the lab outfitted test subjects with harnesses and partially blacked-out glasses and had them attempt to cross surfaces covered in Teflon and other coatings that had been slicked with a carefully formulated contaminant. The test’s purpose was to see how well the friction measurements taken by various tribometers correlated with real-world “human slip experiences.” The result: Different machines testing the same flooring surfaces produced vastly different results. “It’s a mess,” says Christopher Powers, co-director of the USC research team, adding that the status quo helps the industry avoid having to make any big adjustments. “The last thing a floor company needs is someone coming up with the magic number that [shows], oh, by the way, this flooring surface, which is in 60 million buildings across the United States, is slippery when wet.”

Back in Texas, Kendzior is continuing to provide expert testimony. He says a recent trial he testified in ended with a $16 million jury settlement for an oil worker whose boot stuck under a pallet of watermelons, causing him to fall and shatter his elbow. He’s also preparing to petition the CPSC, counting on friendlier faces to be appointed by Joe Biden, the oldest president in U.S. history, who, as Kendzior notes, has been known to wipe out. In October the Senate confirmed a new CPSC chairman, Alexander Hoehn-Saric, and the Biden administration has nominated Mary Boyle, the commission’s current executive director, to fill the open seat. Boyle’s confirmation would bring the commission up to three Democrats and two Republicans, theoretically giving Kendzior a much better shot.

His detractors, though, haven’t relented. Leffler, the forensic engineer, says there remains a lot of work to do to sort out the present slate of competing friction standards. He calls Kendzior a gifted orator but argues that he’s trying to sell the perception of competence as opposed to a technically rigorous and scientifically defensible rating system. “It’d be really nice to state that we could just push the button on the NFSI-blessed device, and what it means is that something is safe for humans or it’s not,” he says. “It’s not that simple.”

Kendzior defends his methods, but he concedes that his decades of work on the subject haven’t ultimately prompted major change when it comes to the industry facing regulatory oversight. At his local Costco, for example, the shopping carts no longer have angled fold-down baby seats, making customers more likely to place their rotisserie chickens flat in their carts and less likely to grease the floor as they wheel through the aisles. But the glistening $4.99 birds still bake under heat lamps inside flimsy clamshell containers that are prone to dripping fat onto the 12-inch-by-12-inch vinyl composite tiles, creating a possible deathtrap. “The flooring industry, I mean, they spend millions of dollars opposing our work every year,” he says. “You take some arrows. But that’s what I signed up for.”

Read next: Nike’s Hands-Free Shoes Are a Fix for People With Disabilities

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.