America’s Largest Private Company Reboots a 153-Year-Old Strategy

America’s Largest Private Company Reboots a 153-Year-Old Strategy

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- William Wallace Cargill pioneered the modern agricultural trading industry in 1865 when he established a string of grain warehouses across the American Midwest. Having a deep-pocketed buyer that could take delivery locally gave farmers an easy way to quickly get cash for their crops, lest they rot in the field waiting on a sale or transport to a faraway market. The ability to store huge amounts of grain also gave Cargill the flexibility to time his own sales to maximize the spread between what he paid farmers and what he could get from distant food processors or exporters.

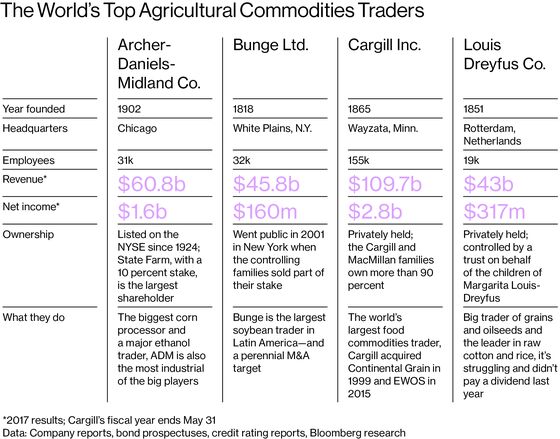

That business model of playing the middleman between farmers and their ultimate customers has enjoyed a lucrative 153-year run, turning Cargill Inc. into the largest privately held company in the U.S. It had revenue of $109.7 billion in 2017 and employed about 155,000 workers—more than the population of Dayton—in offices across 70 countries. And the roughly 100 members of the founding Cargill and MacMillan families who still own the company have become fabulously wealthy, with 14 billionaires among the ruling clan, one of the largest concentrations of wealth in any family-controlled business anywhere in the world.

Yet Minnesota-based Cargill’s business is falling victim to a scourge that’s already upended media, retailing, and other venerable industries: digital disruption. Cargill long made fat profits by having far more information about global commodity prices than the local farmers it negotiated with or the food companies it sold to. But today, even a small Iowa farmer with a smartphone or a tablet can get real-time data about weather conditions and prices facing his Brazilian counterparts. This change has decreased farmers’ dependence on the middlemen and lowered the spread that Cargill and other big buyers used to make on such deals. American farmers have also expanded their in-house storage by almost 25 percent over the past 15 years, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture data, giving them some of the timing flexibility that only middlemen previously had. “The days of ‘Hey, we’re going to buy your crops, we’re going to store it, we’re going to play the carry’—you know, sell it at a profit—it’s over,” says Cargill Chief Executive Officer David MacLennan.

That’s pushing MacLennan to remake Cargill into less of a trading operation and more of an integrated food company betting on growing global demand for proteins. Already the world’s No. 1 supplier of ground beef and the second-largest beef packer in the U.S., trailing only Tyson Foods Inc., Cargill is expanding aggressively into aquaculture. The company is also spending heavily on technology services that will tie today’s internet-connected farmers more closely to Cargill’s slimmed-down trading business or the new farm productivity apps it’s rolling out.

MacLennan, who became CEO in 2013, says he decided three years ago that the company could no longer rely on the occasional crop failure, export ban, or supply shortage to save the day. “I thought, Boy, if we wait for something to change without disrupting ourselves, we’ll be in trouble, ” he says. “What’s that old adage? You put a frog in a pot of water and slowly turn up the heat, and the frog doesn’t notice it’s been boiled. I didn’t want to be the frog in the boiling water.”

His view that farmers increasingly won’t need to rely on agribusiness giants for pricing intelligence is gaining ground within the industry. “We probably [will] witness the disappearance of the dinosaurs of the international agri trade,” says Hartwig Fuchs, a veteran trading executive and, until February, the CEO of Nordzucker AG, one of Europe’s top sugar producers. “Unless they redefine their business and focus on true function that benefits their customers, they might have to go.”

The revolution goes beyond digitization. Agriculture is moving from a pure commodities business, where each bushel of wheat or corn is considered functionally identical, to an ingredients business, where consumers demand differentiation, such as organic produce and foodstuffs grown without genetically modified organisms. That transition makes the life of a trading-based company more difficult, says Jonathan Kingsman, author of Commodity Conversations, because it restricts its ability to find the lowest-priced goods on the market. When traders can no longer “substitute one origin for another, that reduces their ability to make money from the supply chain,” says Kingsman, who once traded sugar for Cargill.

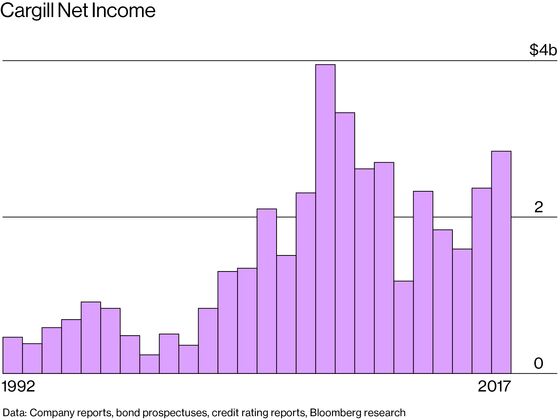

All the changes were certainly the trigger for the current makeover at Cargill, a low-key company accustomed to slow, incremental change. In mid-2015, Cargill reported a quarterly loss—its first in 14 years—followed by several other weak quarters. “It was a strong signal that our performance wasn’t acceptable,” MacLennan says. “It was a company that I felt needed a jump-start.”

He’s tweaked the commodity giant’s portfolio of businesses. Several underperforming units are gone, including Cargill’s energy trading unit, a hedge fund with several billion dollars under management, and extensive pork operations that it sold to meat processor JBS SA for $1.45 billion in 2015. The company is even selling off some of its North American grain elevators. “They’ve chopped a lot of wood,” says Todd Duvick, a managing director at Wells Fargo Securities LLC. “It hasn’t been quick, but it’s been fairly thoughtful and deliberate.”

MacLennan’s biggest shift so far is a large investment in aquaculture, a fast-growing source of protein. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations says farmed fish overtook wild catches as the main source of seafood for human consumption in 2014, replicating the shift that occurred centuries ago in livestock when humans started to raise cows, pigs, and other animals as food. The aquaculture industry’s revenue totals about $163 billion annually, the FAO says.

Three years ago, Cargill bought EWOS, one of the world’s largest producers of feed for the salmon aquaculture industry, for €1.35 billion ($1.58 billion), its second-largest deal ever. And it’s looking for more fish-meal investments. “Certainly the world’s going to eat more fish going forward, so we will continue to invest in aquaculture,” MacLennan says.

Even as Cargill increases its investment in beef and poultry, which it says many consumers consider to be healthier than pork, MacLennan is eyeing new forms of protein in line with the growing appetite for “clean food” in the U.S. and Europe. Over the past year, the company has invested in Memphis Meats Inc., a startup that’s developing beef, chicken, and duck grown directly from animal cells without raising and slaughtering livestock or poultry, and Puris, which manufactures organic and non-GMO protein from peas and other vegetables.

Cargill doesn’t disclose profits by business line, but people familiar with the matter say its animal feed and protein business accounts for about two-thirds of its net income. “While Cargill is best known for its trading business, Moody’s expects that these operations will become a smaller proportion of the company’s earnings and cash flow over time,” says John Rogers, senior vice president at credit ratings agency Moody’s Investors Service Inc.

The corporationwide embrace of technology is also helping Cargill’s traditional business of buying and selling crops. It recently invested in a spinoff from Los Alamos National Laboratory that originally used satellite photographs to track opium crops in Afghanistan for the Pentagon. Now it’s helping Cargill analyze crop conditions with a level of detail that was unthinkable only a few years ago.

Being able to more precisely predict the condition of crops near each of its scores of grain elevators will give it an edge in calculating customized prices to offer at individual facilities, helping maximize profits.When William Wallace Cargill built the company, he helped revolutionize grain storage by constructing more-efficient warehouses with features such as multiple floors and conveyors. Now the company is again betting on agricultural innovations, this time by developing software advances its farm customers can use to increase the efficiency of their own operations.

The company sells software that helps farmers identify individual cows by using facial recognition gear, keep track of what they eat, and measure how much milk they produce to better manage a herd’s productivity. Poultry Enteligen, available at Apple Inc.’s App Store, works with a gadget to scan the quality of animal feed. And the company’s IQuatic system uses microphones to monitor underwater movement to help determine the best times to activate automatic feed dispensers at shrimp farms. “We are trying to bring digital transformation to the industry,” says Neil Wendover, an executive in the Cargill Digital Insights department.

MacLennan is also shaking up the company’s insular culture. Cargill is hiring more computer engineers and software developers and breaking its tradition of promoting mostly from within. In 2013 it hired Marcel Smits from food giant Sara Lee Foods LLC to be chief financial officer. MacLennan has trimmed the company’s layers of bureaucracy, cutting the number of business lines from almost 100 to a dozen, and he’s largely ended the fiefdoms that historically made Cargill more akin to a confederation of businesses than an integrated company. “My belief was we need to be simpler,” MacLennan says. “We need to be in fewer businesses.”

The changes are beginning to turn around Cargill’s finances. In 2017 the company’s adjusted net profit reached a seven-year high of $3 billion, compared with $1.4 billion in 2012, the year before MacLennan took over as CEO. “They have reset the foundations of the company,” says Bill Densmore, a senior director at credit rating agency Fitch Ratings. “The structural changes are profound. They have taken down several hundred million dollars in costs.”

So far, the family shareholders have shown support for the transformation. The company pays the Cargill and MacMillan clan members only the equivalent of 20 percent of the average profit of the previous two years, a pittance compared with payouts of as much as 50 percent across the S&P 500. But with each new generation of the family—the company is now on its seventh—the stake of each individual shareholder gets thinner. At some large family-controlled businesses, that scenario has led to pressure for a sale or initial public offering that would provide a windfall for family members. Rival agribusiness giant Bunge Ltd., for example, went public in 2001, allowing its family owners to sell a large chunk of their stake. Based on price-earnings ratios for its publicly traded peers, Cargill could be worth almost $50 billion.

MacLennan says the company won’t take the IPO route the way rival Glencore Plc, the world’s largest commodities trader, did in 2011. “Statistically, a family company lasts two generations, so we’ve already beaten the odds,” he says. “At 153 years and seven generations, I like our chances of staying private over the long term.”

To make sure that happens, MacLennan says his priority is to learn from other industries, such as retailing, that have already weathered digital disruptions. “I don’t want us to be one of those companies that missed it,” he says, “and that becomes obsolete without even realizing they’re becoming obsolete.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Ellis at jellis27@bloomberg.net, Eric Gelman

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.