Black Neighborhoods Miss Out on Stimulus and Fall Further Behind

A $2 Trillion Rescue Leaves America’s Black Neighborhoods Behind

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Everywhere Miriam Scott looks, she sees an unrelenting crisis closing in on her church and her flock.

On a Saturday in June, her First Love Outreach Ministries handed out more than 20,000 pounds of food, just shy of what it would typically distribute in an entire year. She’s counseled members of her congregation in Cleveland’s impoverished East Side whose relatives have been struck down by Covid-19 and those who’ve lost jobs and are struggling to pay rent. She’s worried she’s falling out of touch with the parade of vulnerable men who head straight from prison to the homeless shelter and used to fill her pews for Sunday services now held on Facebook. She’s not quite sure how she’s going to pay for the new boiler and roof her church needs. Or the past-due electric bill. Every time she flicks the light switch, she does so with a little prayer that there will be light.

What Pastor Scott worries about most, though, is that this pandemic is going to take away the church she and her husband, Robert, have spent more than a decade building between their shifts as corrections officers. And, more important, that losing the church will leave those who rely on it in a neighborhood where more than half the people live below the poverty line searching for a new spiritual home as the nation deals with its own epochal predicaments.

In a pandemic that’s wreaked widespread economic havoc, Cleveland has been among the hardest hit cities in the U.S. Its unemployment rate peaked at 23.1% in April, after one-fifth of its labor force, mostly lower-income service workers, lost their jobs in a matter of weeks. Yet Scott’s accumulating emergencies represent the all-too-easily forgotten collateral damage. A tiny church serving a vulnerable corner of American society is having a life-or-death moment that will never show up in the data. And it’s doing so with little help at a time when the government and economists are hailing all that’s being poured into the economy and calling for more.

“I’m literally on the last thousand dollars in the bank,” Scott says one morning in June, her eyes tearing up as she sits among plastic bags full of food ready for distribution that fill the pews where people once sat. Yet every time she goes looking for help, “all the doors are shut.”

The $2 trillion rescue that Congress passed in March ranks among the most aggressive in history. Viewed through the aggregate data, there’s no doubt that the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act has saved the economy from a slide into depression and helped millions of families weather the initial plunge into lockdown. Its $1,200 stimulus checks, enhanced unemployment benefits, and flood of money for small businesses, along with the billions of dollars the Federal Reserve has pumped into financial markets, are an expression of an American policy elite that has at times seemed determined not to repeat the mistakes of the last crisis. Concerns about deficits, debt, and inflation have been set aside. The consensus these days has rallied around a whatever-it-takes approach that, though focused on businesses and markets, has included social programs setting new benchmarks for economic impact.

And yet in Cleveland’s predominantly Black neighborhoods, their streets pockmarked with vacant lots and abandoned buildings, home to childhood poverty levels that rival those in developing nations, you find lots of stories like Scott’s that are emblematic of who’s being left behind.

At a time when the U.S. is engaged in another conversation about its foundational racial inequities, the rescue is amplifying those imbalances in places like Cleveland, where half the population is Black, and fueling the anger of a new generation in communities too used to being left out.

“I’m not going to play my people for a fool,” says Stephen Rowan, pastor of Bethany Baptist Church, pointing to what he sees as a pattern where wealthy institutions such as the nearby Cleveland Clinic receive $200 million in Cares Act help and increasingly frustrated members of his congregation miss out. “There comes a point in time when I cannot justify or say to them that ‘God will make a way’ despite what they are seeing right in front of their face.”

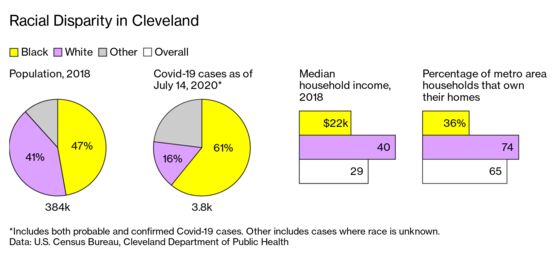

The coronavirus has hit Cleveland’s Black communities hard. Black patients account for 61% of the city’s more than 3,777 identified cases, as of July 14. White ones made up just 16%. The virus has also reinforced the city’s long-standing gaping economic disparities between largely Black neighborhoods east of the Cuyahoga River and predominantly White ones to its west. At $21,769, the median income of Black households in the city in 2018 was about half the $40,485 of White ones. The legacies of decades of redlining and other discriminatory lending policies are plain to see. Roughly one-third of Black households own their homes; three-quarters of White ones do.

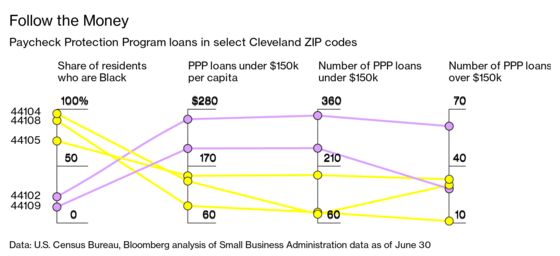

Data released this month by the federal government on the Cares Act’s Paycheck Protection Program underscore these inequities. In the 44102 zip code between Cleveland’s downtown and the affluent suburb of Lakewood, where 47% of the population is White, small businesses received 343 loans of less than $150,000 each, for a total $11.9 million, or $260 per person. In the 44104 zip code, home to Scott’s church and a population that’s 96% Black, small businesses received just 83 loans of less than $150,000 each, for a total $2.8 million, the equivalent of $140 for each resident. The disparity is similar for loans greater than $150,000: as much as $60 million in 44102 compared with $27.4 million in 44104.

For those who live on the East Side, it’s a repeat of an economic pattern that last manifested itself in the foreclosures that accompanied the financial crisis more than a decade ago, but one with 400-year-old roots in slavery.

Tony Jones, who owns T.J.’s Barber Shop, a three-chair affair with photographs of Muhammad Ali, Barack Obama, and members of Jones’s family on one wall, thrusts his phone forward and says, “Have you got six minutes? Watch this. Then we can talk.”

Loaded up is a video in which author Kimberly Jones (no relation) likens the economic travails of Black Americans to a centuries-old Monopoly game in which White players get a pile of cash to start and Black ones get nothing. Worse, whenever Black players build up a little wealth, the White players take it away. The protests that hit cities including Cleveland after George Floyd’s death, the video argues, are the equivalent of Black Americans upending the board in anger. “See,” the barber says. “It’s all about economics.”

The economics for Jones have only gotten grimmer. He was forced to shut his shop in March as Ohio locked down. Since reopening on May 15, he’s had a trickle of customers. Some days just two people sign the logbook near the door that he’s required to keep. Jones never tried to get a PPP loan for himself and his one employee. It seemed too complicated. He filed for unemployment, only to become one of the almost 380,000 Ohioans, about 30% of those applying, who’ve been deemed ineligible for traditional unemployment benefits since March.

State officials only began accepting applications for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance, the Cares Act program that expands benefits to self-employed workers like Jones, on May 12, three days before barber shops were allowed to reopen. But Jones’s application for retroactive benefits was denied after he was told he didn’t pass a threshold for weeks worked over the past year, leaving him to pay the rent from his savings and to absorb the lost business and the cost of masks, disinfectant, and other equipment he needs to operate while waiting for customers still too afraid to sit in one of his light-green chairs.

His business crisis has been amplified by a family one. One of his sons worked with coronavirus patients for a time, and by the end of June had been hospitalized for anxiety attacks. “Every time it feels like we’ve gained 10 yards, we get pushed back 15,” Jones says.

Across 105th Street from T.J.’s, Rowan’s Bethany Baptist Church applied for and received a PPP loan that allowed it to keep paying staff. But many in its congregation have been less lucky. Ellwood Clark, a Bethany deacon, applied for a PPP loan for his home-maintenance business when the program became available, but his application was kicked back by his bank when the first round of funds quickly ran out. He was told to wait for a call that never came. “My bank didn’t call me, and I’m quite sure the big companies got calls,” Clark says. Rather than wait or apply for unemployment, he’s opted to cobble together what work he can.

Even with its PPP funding, Bethany Baptist has been forced to scale back. Kingdom Korner, a storefront next to the barber shop that the church uses to provide counseling and other services to community members, has been closed since March. Its weekly legal aid clinics are on hiatus for now, which means a popular program to help local residents expunge criminal records is on hold. It’s a key step for many job seekers in a community where too many men have spent time in prison, says Adrianne Thomas, Kingdom Korner’s director.

In a tight labor market, a felon has a chance of finding a job. In a world of double-digit unemployment, a criminal record is an easy excuse for an employer to choose someone else. That matters in Cleveland, which has one of the highest incarceration rates in the country, according to the Prison Policy Initiative, an advocacy group. “People say they hire felons,” Thomas says. “But that’s only a small number of people.”

The issue of criminal records has had other repercussions. The Small Business Administration, which administers the loan program, initially barred anyone with a criminal conviction within the past five years. The rule was changed after Ohio Senator Rob Portman, a Republican, intervened on behalf of a constituent with a conviction who ran a small business that hired other workers with criminal pasts.

The criminal record exclusion was emblematic of the ways in which the Cares Act, assembled hastily over 10 days of bipartisan negotiations, inadvertently discriminated against the Black community, Portman says. “We just didn’t think through all this stuff, because it’s hard to.”

Portman and Senator Sherrod Brown, Ohio’s senior Democrat in Washington and a resident of Cleveland’s East Side, insist that focusing on the relief act’s shortcomings misses the bigger story of a depression averted. They’re also working on what comes next, which could affect how an increasingly competitive state votes in November. Brown is pushing for an extension of the $600-a-week boost in unemployment benefits beyond its expiration at the end of July. Portman wants a $450-a-week back-to-work bonus to replace it to counter the disincentive some small-business owners say that enhanced unemployment benefits create. Other Republicans would like to see the bonus disappear altogether. Unless a compromise emerges, economists warn of an economic cliff, meaning another wave of disaster would hit cities like Cleveland.

Brown and Portman say they want to see more targeted help for Black-owned businesses in the next stimulus bill. The pandemic, Brown says, “revealed all the racial disparities in our country, in health care and housing and jobs and the economy overall, in education. And Congress has fallen short.”

Whatever emerges will also need to embrace a bigger conversation on race and economics. To Blaine Griffin, a city councilman who represents some of Cleveland’s poorest neighborhoods, all the rescue efforts, all the disparities, all the people still left out are a consequence of the broader reality that racism is a public health crisis of its own in Cleveland.

Griffin was the architect of a vote in June declaring just that. The move didn’t mandate any action. But the 49-year-old former community activist, who once ran a program to reintegrate violent offenders coming out of prison into their communities, argues that to fix a problem you have to diagnose it first. Plus there’s little doubt that the economics of racism have health consequences for his constituents, who’ve long battled what Griffin calls pandemics of crime, lead poisoning, and chronic unemployment.

A child born today near the corner of 110th and Woodland in Griffin’s ward has a life expectancy more than two decades shorter than one born in an affluent neighborhood two miles away. “This right here is the epicenter of all of those pandemics coming together,” Griffin says, waving his arms across the intersection one morning in June.

And that is unlikely to change as a result of any of the rescue efforts coming from Washington, he argues. Stimulus checks and unemployment benefits have helped pay off his constituents’ bills. Some small businesses have received loans. But no one’s trajectory has changed. “The Cares package, in my opinion, has not been friendly to any urban core that I know of in the United States. And it definitely has not been here in Cleveland.”

Bridget Ferguson and her five children under the age of 8 moved into Griffin’s ward in June. They were supposed to have left Laura’s Home, a women’s shelter, in March after more than a year crammed into a single room filled with bunk beds. But the move was delayed when schools and day care centers closed and the pandemic killed her hopes of landing a job.

Ferguson, 28, got tired of waiting and found a three-bedroom home with a backyard. She has vouchers to cover the rent for the next six months as well as child care. Her small pot of savings was boosted by her $1,200 federal stimulus check and one for the father of one of her children who’d fallen behind on child support. She has hope, even job leads. “I want to be working,’’ says Ferguson, a culinary school graduate.

But she also knows she will have to start paying $900 a month in rent in six months, and she’s looking for work in a pandemic-stricken economy. A job in a kitchen isn’t an option in a world where restaurants are closing for good and hotels have skeleton staffs. More important, she still needs to find day care—not an easy proposition when public health guidelines are forcing centers to cut capacity.

Scott, the First Love pastor, will be the first to tell you how hard it is to change trajectories. Even in normal times, her church had a tenuous existence. A 10-minute drive from downtown, it sits in an area long dubbed the city’s “Forgotten Triangle.” More than half of the residents in the church’s zip code, and three-quarters of its children, live below the U.S. poverty line.

When Scott and her husband bought the 120-year-old building for $15,000 eight years ago, they had to call the city to tow away abandoned cars. Then they had to coax visitors down a dead-end street that housed little else. Until the pandemic, the church eked out an existence on $300 to $400 in weekly tithes, supplemented occasionally by Scott and her husband.

When Ohio ordered a lockdown and Sunday services stopped, so did the weekly donations. But not the bills. The boiler died in the spring. The refrigerator conked out a few weeks back, and the fragile freezer next to it is straining. She needs $18,000 to fix a roof with gaping holes. The electric and gas bills haven’t been paid for months.

Scott also started seeing demand for food surge and organized weekly distributions of milk, cheese, and produce that she managed to get through the Cleveland Food Bank. When the fridge died the night before one distribution, she and her volunteers laid the milk and eggs out on the pews and maxed out the air conditioner to keep the perishables cool.

Scott and her husband each received $1,200 stimulus payments that have covered such church costs as renting a van to pick up food donations and paying for cleaning supplies and masks. She thought she might be eligible for a federal small-business loan for faith-based institutions. But when she looked up the criteria online, she found the church didn’t qualify because no one at First Love is paid. She has explored other grants and loans but found nothing.

The idea of reopening for in-person services terrifies her. She’s also confronted with the diverging paths before her every time she shows up to check on her church after her overnight shift at one of the county jails, where fears of a Covid-19 outbreak have added to her angst.

In the abandoned white clapboard church next door to First Love, she sees a terrifying omen. “You take out a church like this that does nothing but outreach in an impoverished neighborhood, and it is like cutting off someone’s leg,” Scott says. “I do believe that because of what we do, we’ll make it. But we do need help.” —With Jason Grotto, Wei Lu, and Laura Davison

Read next: Coronavirus Conversations With One of America’s Richest Men

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.