Businesses Flock to Baltimore Wasteland in Epic Turnaround Tale

Businesses Flock to Baltimore Wasteland in Epic Turnaround Tale

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Sparrows Point looked like the backdrop to a dystopian sci-fi flick when Roberto Perez first laid eyes on it in the summer of 2012. Located along Chesapeake Bay in Maryland’s Baltimore County, the site housed what was once the world’s biggest steel mill as well as a shipyard. Scrap metal and giant machinery littered the landscape. The soil and water were laced with toxins.

When he heard Sparrows Point’s owner, RG Steel LLC, had filed for bankruptcy, Perez chartered a flight from Chicago for his team to see what could be salvaged. At a minimum, his employer, Hilco Global—a company that specializes in selling distressed assets—could strip Sparrows Point for parts and make a quick profit. Perez, who as chief executive officer of Hilco Redevelopment Partners oversees the group’s real estate investment activities, had an inkling there might be other ways to wring money from a 3,100-acre spread of industrial land with its own deep-water port, 100 miles of shortline railway, and easy access to an interstate highway—all within a day’s drive of about a third of the U.S. population.

Less than three months later, Hilco and an investment partner purchased Sparrows Point at auction, paying $72 million. “It was insane,” Perez says. “We literally bought a city.”

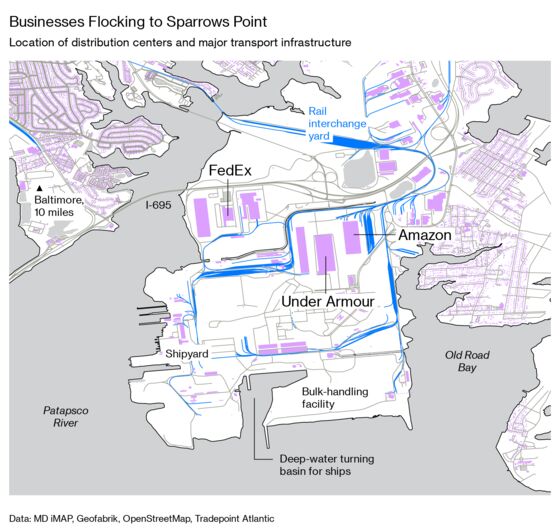

Fast-forward seven years, and Sparrows Point has been transformed into Tradepoint Atlantic. Amazon.com Inc. and Under Armour Inc.—the sports clothier run by Baltimore booster Kevin Plank—have leased almost 2.5 million square feet of warehouse space between them. Other tenants include FedEx, Volkswagen, and Harley-Davidson. Officials at Tradepoint are projecting that private investment will reach $2 billion by the time the operation is at full development in 2025. About 4,000 work at the site at present, counting construction crews. Total employment, a figure that includes indirect jobs generated by the project, is expected to swell to 17,000 in a few years’ time.

Sparrows Point is more than a tale of revival on the doorstep of a city that Donald Trump has reviled as a “disgusting, rat and rodent infested mess.” It’s a counternarrative to the president’s Make America Great Again formula, which privileges manufacturing above other industries. Here on the edge of Baltimore, a Rust Belt city that was hollowed out by forces of globalization, services such as e-commerce and logistics are powering a renaissance. The majority of the businesses that have set up shop at Tradepoint aren’t trying to roll back decades of trade liberalization. They’re thriving because of it. Trump often rails about the size of America’s trade deficit. What he doesn’t mention is that the U.S. consistently logs a large services surplus with the rest of the world.

“When you think about it philosophically, you had the steel mill and the conversations about the global economy impacting American industry and putting it on its knees,” says Tradepoint spokesman Aaron Tomarchio. “Now this place has a global footprint, and the global economy is helping fuel the success here.”

In Sparrows Point’s glory days, the blast furnaces owned by Bethlehem Steel Corp. supplied metal for the Golden Gate Bridge and Empire State Building. Boats welded at the shipyard helped America win both world wars. At the peak in the 1950s, workers numbered more than 30,000. There was a company town, complete with a hospital, schools, stores, a streetcar line, and a cemetery.

Alan Thompson worked at the steel plant from 1995 until it closed in 2012. “It was flames everywhere, sparks flying, molten steel,” he recalls. The hulking monster produced smog and red dust that blanketed the town, plus a tremendous amount of noise. It was “music to my ears,” says Thompson, 61, whose father was born in the Bungalows section of the town and later found employment at the mill and the shipyard. “That means a lot of people are making money!”

Jerry Ernest, 68, also followed his father into the steel mill—and stayed for 43 years. It could be dangerous work. He remembers losing three colleagues, including one who tumbled into a vat of hydrochloric acid. But wages were more than decent, and there was free health care and a pension. “It was a good job,” Ernest says. “No one really understood how good it was until it was gone.”

The beginning of the end came in 2001, when Bethlehem Steel filed for bankruptcy, blaming competition from cheap imports, spiraling debt, and crippling pension obligations. Over the next dozen years, Sparrows Point changed hands several times. (At one point it belonged to Wilbur Ross, the veteran dealmaker whom Trump drafted to be his commerce secretary.) RG Steel completed its purchase in March 2011; the company filed for Chapter 11 protection just 13 months later. By that time the number of employees had dwindled to just 2,000.

Hilco arrived with low expectations. More than a century of steelmaking had left the area badly polluted. Refuse from the steel furnaces called slag was dumped so frequently into the Chesapeake Bay that today it forms most of the existing landmass at the site. A 2009 review by state authorities had revealed highly toxic levels of benzene, chromium, and zinc in the groundwater. The site “was perceived by everyone to be environmentally unsolvable or certainly too scary to get involved with,” says Eric Kaup, Hilco’s general counsel.

Perez persisted, knowing there would be ready buyers for the leftover raw materials and equipment. Hilco teamed up with a St. Louis, Mo., company that assumed all of the environmental liabilities. Together they paid less than one-tenth of the $810 million Sparrows Point had previously sold for.

When Hilco sold a state-of-the-art cold mill to Nucor Corp. for parts at the end of 2012, it was clear that Sparrows Point’s steelmaking days were done. Much of the rest was demolished and sold as scrap. “To watch that old girl that I worked on, and generations before me, just torn down—it broke my heart,” Ernest recalls.

As Perez and other Hilco executives clocked more hours at the demolition site, they began to hatch a plan. “About 18 months in, we realized that the land was actually the most valuable part of the deal,” says Kaup. In 2014, Hilco and Redwood Capital Investments LLC, a firm backed by Baltimore billionaire Jim Davis, formed a joint venture and bought out Hilco’s original partner in the auction. The companies reached an agreement with the Environmental Protection Agency that allowed them to start remaking Sparrows Point into a logistics hub while environmental remediation work continued. As a condition, the companies were required to place $48 million in a trust to cover the cost of the cleanup in the event the venture failed.

Sites like Sparrows Point where redevelopment is complicated by the presence of pollutants are called brownfields by the EPA. Todd Davis, CEO of Hemisphere Brownfield Group, whose company specializes in rehabilitating these type of properties, reckons that Sparrows Point may be the largest of the 450,000 or so in the U.S.

The National Brownfield Association estimates that almost $1 trillion of real estate value could be unlocked from these sites, many of which have features that are appealing to developers, including waterfront locations, transport links, and proximity to large urban populations. But many investors won’t touch brownfields because of the expense and regulatory burden. Says Davies: “You have to be eminently patient to move through the process, and you have to have an appropriate risk tolerance.”

Hilco and Redwood created Tradepoint to oversee Sparrows Point’s transformation. Eric Gilbert, the venture’s chief development officer, recalls that area residents were initially skeptical when officials outlined their plans in town-hall-style meetings. “When we said, ‘We’re going to rebuild the roads and water and sewer, we’re going to bring thousands of jobs and big-name companies,’ well, we got a lot of rolling eyes.”

One of the first things Tradepoint did at Sparrows Point was to build a 1 million-square-foot warehouse—about the size of 17 football fields—the same way a developer might put up a spec home to show to prospective tenants. The first company to sign on was FedEx Corp., which opened a distribution center in late 2017, bringing with it about 300 positions. The number of tenants is now 15 and counting. More than 3,000,000 square feet is under construction for Home Depot and Floor & Decor, while a Gotham Greens hydroponic greenhouse is set to open later this year.

The warehouses, enormous as they are, only take up a fraction of the land at the site. Half a mile away, giant yellow dump trucks crisscross a construction site. Tradepoint’s plans call for adding 15 million square feet of space—mostly industrial but also some retail.

On an afternoon in May, the parking lot of the new Amazon fulfillment center is bustling with activity. Workers line up at a food truck for $13 crabcakes. A woman gathers her belongings before walking into orientation on her first day at work. Two guys sit in a car rolling a joint during a shift break.

Over by the port, stacks of aluminum destined for car manufacturers cover an area roughly the size of two city blocks. Tradepoint is spending about $50 million on upgrades to the facility, so it can accommodate higher tonnage vessels.

Executives at Hilco and Tradepoint say initially there was apprehension in the local community about whether the jobs being created would be as good as the ones they were replacing. The short answer is: not quite. The median wage for an order filler at a warehouse is $15.35 an hour, compared with $19.34 for a metal furnace operator, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“If all 17,000 jobs were of the caliber, salary, and benefits of the steel plant, I think any local jurisdiction or state or country would be doing back flips,” says Johnny Olszewski Jr., the executive of Baltimore County, who grew up in the shadow of the Bethlehem Steel mill. “But I think in many ways the economy has shifted.”

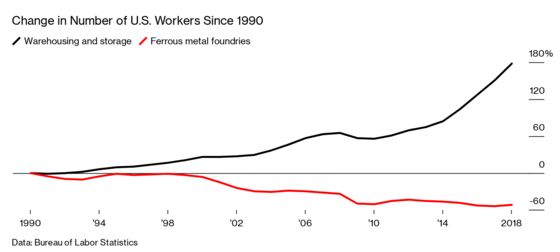

And not just here. Nationwide, warehouse jobs have more than doubled in the space of a decade, to reach almost 1.4 million in 2018. Automation will eventually start eating into those numbers, the way it has in the steel industry. Consider that the U.S. produces about as much steel today as it did in 1990 while payrolls have dropped from more than 180,000 to less than 85,000 today, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the World Steel Association.

“If you’re lazy, it’s not for you,” says Ameera Toyer, whose job at Amazon’s warehouse in Sparrows Point consists of putting items on different machines and pushing a button that labels and packs boxes. Her quota is 700 per hour. “I hit 900 an hour once,” says the 20-year-old. “It’s all in the hands.”

Toyer says the work is boring, but the $15-an-hour pay beats what she was making previously as a manager at a fast-casual restaurant. Most days she works more than her 10-hour shift to get overtime. Plus, in October she’ll have been with Amazon a year, which means she can go back to school to become a social worker and have the company pay her back for 95% of the cost. “It’s good for now,” she says. “There’s a lot of benefits to working here.”

Locals have other reasons to be thankful for the changes taking place at Sparrows Point. With the mill’s closure, a perennial source of toxins has been removed. “This is the best thing that could have happened to the site,” says Paul Smail of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, which sued Bethlehem Steel in the 1980s over discharges of pollutants into the surrounding waterways. Remediation work at the site is about halfway done, according to Tradepoint.

In a development that underscores how Sparrows Point is staking its future on the new economy, Tradepoint announced in July that it was leasing 50 acres to Orsted A/S, a Danish company that’s building an offshore wind farm some 20 miles off Maryland’s coast. Orsted will ship components to Sparrows Point so the turbines can be assembled there.

Officials at Tradepoint are also looking to rehabilitate the shipyard on the premises, which has been little used since the turn of the century. The massive dry dock can still accommodate ships, and they’re hoping to bring in a tenant who’ll use it to repair and refit navy boats. “We’d love to have a big manufacturer here,” says Tomarchio, the spokesman, but “we have to be realistic about what kind of industry is going to be coming here.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net, Pierre Paulden

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.