All the Democratic Health-Care Proposals Have One Big Problem

All the Democratic Health-Care Proposals Have One Big Problem

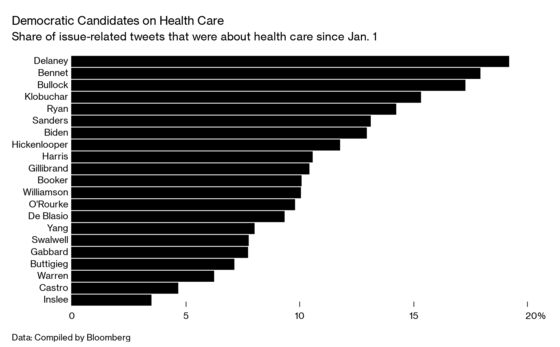

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Democrats are engaged in a vigorous debate about how to achieve their goal of universal health-care coverage. Moderates such as Joe Biden want to enhance the existing Affordable Care Act with a “public option.” Progressives like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren want to junk private insurance and set up a “Medicare for All” system. But looming in front of the discussion is an obstacle no amount of careful messaging will help them overcome: Even the most modest Democratic plan would face intense opposition from health-related industries, not to mention Republicans.

Already, powerful interest groups are mobilizing and pooling resources to undermine the Democrats’ plans. The Partnership for America’s Health Care Future—a lobbying group that represents insurance companies, drugmakers, hospitals, and other industry players—is running TV ads and commissioning polls designed to undercut support for any expansion of government-provided coverage.

The industry coalition despises Medicare for All, which would end private insurance, hammer pharmaceutical profits, and slash provider payments as much as 40% in the hope of making coverage universal and accessible. But the group’s also against letting Americans buy into a Medicare-like plan at lower cost. “We want to build upon what is currently working and fix what is not,” says Lauren Crawford Shaver, the Partnership’s executive director, who worked in the Obama administration and on Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign. “Candidly, we do not see Medicare for All, Medicare buy-in, or public option helping to accomplish those goals. Our members are not really together on many things in this town, but they are united in this.”

So far, voters disagree. A July poll commissioned by NPR and Marist found that 41% of Americans favor a Medicare for All plan that replaces private insurance, while 70% said they support having the choice of being covered by a government-run plan or private insurance. A public option may poll well now, Shaver says, but “people genuinely don’t know what it means.” Once the industry makes its case about what a government-sponsored plan would mean for people’s coverage, she expects opinion will change.

Its recent six-figure TV and digital ad campaign, rolled out nationwide, is just the first step. “The politicians may call it Medicare for All, Medicare buy-in, or the public option,” say a rotating cast of seemingly ordinary people. “But they mean the same thing: higher taxes or higher premiums, or lower-quality care.” The industry coalition argues that Medicare for All could pummel rural physicians and cause many hospitals to close. Proponents have responded that only insurance would be centralized and that the program would allow all Americans to go to doctors and hospitals of their choice. But the real impact on the industry depends on the extent of reimbursement cuts to providers, a detail that remains unspecified in many Democratic proposals.

The lobbyists may not have a vote in Congress, but they have demonstrable influence over the legislative process. Ask Jim Manley, a former Democratic aide who began his two-decade Senate career a few years before Bill Clinton tried to pass universal health care. He saw the bill run into a buzz saw of opposition after insurance lobbyists ran a multimillion-dollar TV campaign in which a couple named Harry and Louise lamented being stuck with bad government options.

A decade and a half later, Democrats held painstaking negotiations with key industry figures to neutralize opposition. Insurers would come under tougher rules and have to cover people with pre-existing conditions at reasonable rates; drug companies would pay rebates for some prescription medication; doctors and hospitals would face some payment cuts. But they’d also be guaranteed millions of new customers thanks to the subsidies that extended coverage. The result was the Affordable Care Act—or Obamacare.

“One of the big takeaways from Clintoncare is, when you have a powerful opponent such as the health-insurance industry, it’s very difficult to get anything done,” says Manley, who worked for then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid when the ACA passed with not a vote to spare. “They managed to demonize the issue and make it radioactive to many Democrats. Which is why the takeaway from Obamacare was to try to build a coalition to take away some of those politics.”

Even if Democrats win the White House, hold the House, and regain the Senate, their best-case margin in the upper chamber would fall far short of the 60 votes needed to pass legislation. Republicans, who in 2009 and 2010 refused to supply a single vote for Obamacare, aren’t likely to sign on to any Democratic idea. One Senate Republican aide, speaking on condition of anonymity, says the majority has no intention of compromising on a public option, calling it a “radical” idea no matter how moderate the candidate.

Manley doesn’t see single-payer getting the kind of support it would need to overcome Republican and industry opposition. A public option may have more Democratic support, he says, “but it’s fair to point out that these are very powerful interests that are prepared to oppose just about anything that’s being discussed right now.” Industry players killed it in 2009, and this time, just like last time, “there’s a whole bunch of groups that are dead set against it.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.