Anger Is Spreading in a Tinderbox on Europe’s Doorstep

Anger Is Spreading in a Tinderbox on Europe’s Doorstep

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- It’s just after 8 p.m. in Algiers and the curfew imposed by the government to stop the coronavirus’s spread has been in effect for 15 minutes. Around this time each evening, when the blazing summer heat eases, three friends meet in the city’s western suburbs to smoke and mull the latest pandemic news.

Despite the rules on movement and public gatherings, they don’t fear arrest. This working-class area of the Algerian capital has always been difficult for security forces to patrol. Now they don’t dare visit at all, reckoning that anger and despair could easily explode into riots.

“As long as you’re in your rat hole, you can do whatever you want,” says Madjid, 36, the oldest of the trio. “It’s as though they even wish for our deaths.”

In a world growing more restless during the pandemic, such resentment against the authorities resonates more in a country with such a history of conflict on Europe’s doorstep.

Before the onslaught of Covid-19, Algeria was already home to peaceful weekly protests against a political system still rife with cronyism following last year’s resignation of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika and a deteriorating oil-dependent economy that remains controlled by the military-led elite that’s ruled since independence from France in 1962.

The North African country has defied many expectations of a sharp deterioration in public order. But when the health crisis subsides, observers say it is inevitable that pro-democracy rallies start again with renewed vigor. What form they take will decide where Algeria goes next, and whether the leadership can make enough concessions to avoid an escalation in civil unrest.

The next stage could be nationwide strikes and more regular street demonstrations. “When people become more desperate, there’s the possibility of more radical extreme action because they think it would be a way of extracting more from the government,” says Riccardo Fabiani, North Africa project director at think tank Crisis Group.

The leaderless protests, known as “Hirak,” or “Movement” in English, spans all generations, but it has been shaped by a deeply distrustful youthful population. The secular and religious, different tribes and ethnic groups have all marched together, in an unprecedented display of national unity. So far, their list of demands is purely political centered around a “new republic,” and includes an easing of curbs on speech and the media.

Having learnt lessons from the 2011 Arab Spring as well as Algeria’s civil war of the 1990s, protesters have reminded each other on social media to avoid violence.

On the streets, they chanted “silmiya, silmiya,” or “peaceful, peaceful,” and handed out white roses to riot police. They cleaned up after each rally and when Covid-19 began to take hold, it was the activists themselves who called for a pause to help protect public health before the government announced restrictions on March 17.

Merouane, a 28-year-old unemployed construction worker and one of the trio in the western suburbs, is eager to get back onto the streets—with a caveat. To survive, he says, the movement must evolve. Last year, calls for more action were never heeded. Now they might be. “If it doesn’t change its strategy, it will be like one who plays music to a deaf person,” says Merouane.

This isn’t the first time that Algeria’s dispossessed youth has risen up against the system. In 1988, thousands rioted in central Algiers over redundancies, unreliable water supply, an absence of basic foodstuffs and the sharp rise in the price of school materials. In 2001, during the so-called Black Spring, authorities fired at protesters in the Kabylie region and killed more than 100 people. A decade later, protests inspired by the Arab Spring were nipped in the bud.

This time around, the trigger was Bouteflika submitting a bid to run for a fifth term, despite being in his early 80s, ailing and rarely seen in public. But rather than dissipating, the protests continued since Abdelmadjid Tebboune took office as president in December after winning elections on a record-low turnout.

For Madjid, after four months of lockdown and having lost his job at a state company, it’s a matter of dignity. He has hope, though knows the worst may be yet to come.

“It’s the same authoritarian practices that continue, nothing changed in the end,” he says. “They’ve made the people who are impatiently waiting for Hirak to start again even angrier, and when it does start again, it will be bigger and more radical.”

For years, the rulers of the OPEC member tried to deploy oil wealth to keep a lid on pent-up frustration. That became more challenging when global prices started to slump in 2014 and foreign currency reserves dwindled.

Before the coronavirus began killing Algerians in March, life was getting harder. Last month, with only about two years’ worth of reserves left, the government was forced to cut imports by $10 billion and spending by half, while promising not to touch subsidies covering food, energy and housing.

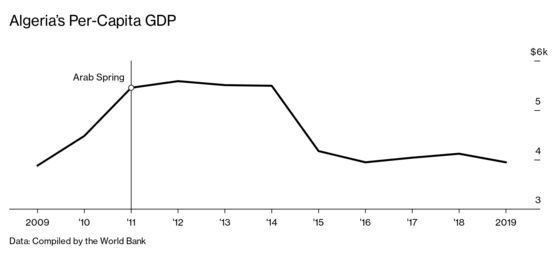

Per-capita gross domestic product remains higher than neighboring Morocco, which is seeing its own rumblings of discontentment during the pandemic as the kingdom rolls back on promises of democratic reform. Yet while Morocco’s has remained at around $3,200 over the past five years, in Algeria it declined by more than 25% to about $4,000, according to World Bank data.

A thriving black market that allowed families to get by has collapsed because of supply chain disruptions. Businesses are shuttered. Fruit and vegetable sellers are low on produce. The lack of basic infrastructure, like hospitals, is more glaring than ever.

Tebboune, 74, has ruled out following a growing number of Arab and African countries in shedding taboos to borrow from the International Monetary Fund, arguing that would curb Algeria’s ability to pursue an independent foreign policy. He’s left the door open to approaching China for help.

Yet the regime appears uncertain about where to go next as it’s confronted with an anger that won’t go away and can’t be bought off.

That’s largely because the army is split in two camps, Algerian columnist Elkadi Ihsan wrote in the online newspaper Maghreb Emergent on June 27. One wants to use force and repression that the past year has largely avoided. The other wants dialog, but only with less radical activists.

These two conflicting tendencies, he said, help explain why the regime oscillates between extending a hand and cracking down. In early January, 58 prisoners of conscience were released only for 173 activists to be jailed during the lockdown. It’s impossible to know which side of the elite has the upper hand, Ihsan said.

During the early days of the protests, the mood was euphoric. Algerians who’d been living abroad even began to return to help build the country anew, free of economic mismanagement, corruption and repression. When it became clear the regime wasn’t going to give up so easily, illegal crossings to European shores resumed and the brain drain continued.

In the western suburb of Algiers, a cool breeze blows in from the Mediterranean Sea that’s visible from the terraces of some homes. Small groups of people crisscross the street, others play dominoes. Staring down at their smartphones, cigarettes hanging from their mouths, Madjid, Merouane, and Anis, the youngest at 24, contemplate an increasingly uncertain future.

Anis hopes to move abroad once he finishes his studies. In the meantime, he will join his friends in the streets as soon as marches resume. The aim, he said, is to force “radical change.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.