Canada’s Oil Capital Gets Its Own Separatists

Canada’s Oil Capital Gets Its Own Separatists

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- It’s not just the Quebecois who sometimes imagine themselves breaking away from Canada. Ever since Liberal Justin Trudeau was reelected as Canada’s prime minister in October, a small but vocal group in the oil-rich province of Alberta has worked to rally support for seceding from the country. The separatists complain that climate crusader Trudeau is working to cripple the oil industry, and that the province sends too much in taxes to Ottawa and gets too little in return.

The so-called Wexit movement, named for Alberta’s location in western Canada and inspired by the U.K.’s separation from the European Union, was on display at a November rally in Calgary, where most of Canada’s energy companies are based. The event drew about 1,700 people, some wearing hats emblazoned with “Make Alberta Great Again” and “WEXIT” in all caps. Speakers, including the movement’s co-founder Peter Downing, spoke directly to Albertans’ frustrations, painting a picture of an independent Alberta flush with cash, freed of the burden of federal taxes, and driven by a booming oil industry no longer restrained by regulations imposed by eastern elites.

They also appealed to by-now-familiar right-wing fears, warning about unvetted immigrants and the creep of communism. They elicited boos while lambasting the media and riffed on cultural grievances such as the firing of hockey commentator Don Cherry over a comment questioning immigrants’ patriotism. The Wexit movement isn’t about white supremacy, Downing said, noting that his own wife is an Asian immigrant who didn’t grow up speaking English. “It’s not about any kind of race or religion.” Those trying to tar Wexit with the brush of racism are grasping at straws, he said. “The establishment is scared when western Canadians stand up for their rights and aren’t going to be pushed around anymore.”

Calgary was just the second stop on a five-city tour Downing has been on since the election. He and others in his organization, which includes local businesspeople and activists, have drawn crowds in Edmonton and Red Deer. In less than two months, they’ve managed to harness the region’s simmering resentments and turn them into a roiling movement. According to an Abacus Data poll conducted in the week leading up to the Calgary rally, about 25% of Albertans would vote in favor of separation—less than half the support it would need to put separation proceedings in motion, but enough to make it more than just a fringe concern.

Kimball Daniels, a 54-year-old who works in the construction industry, says he’s long considered the question of whether the province should separate from Canada, but Trudeau’s reelection was the last straw. “It’s taxation without representation, simple as that,” Daniels said while waiting for the rally to get under way. “They take our money, and we have no say in it.”

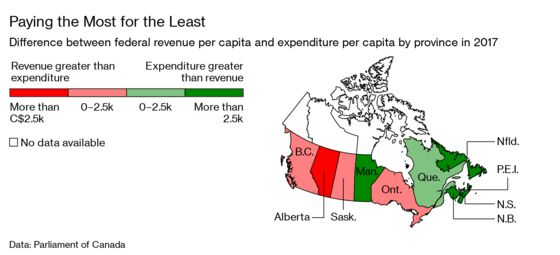

Albertans contribute disproportionately to federal coffers, paying about C$5,096 more in tax revenue per capita than they received in government spending in 2017. By contrast, Quebecois received C$1,958 more than they paid. (Alberta also has a higher per capita gross domestic product than does Quebec.)

Other Wexiteer criticisms are more difficult to square. While Trudeau has imposed a carbon tax and banned most crude oil tankers from part of Canada’s Pacific Coast, he’s also worked to support the energy industry, shelling out C$4.5 billion of federal money to save a key oil pipeline expansion project from cancellation and denting his image with the Liberals’ environmentalist wing in the process.

Crucially, the separatists have yet to deliver a robust explanation as to how Alberta would be better off as a landlocked, oil-focused nation in a world moving away from carbon-based fuels. They say that an Alberta freed of Ottawa’s influence could forge better trade relations with the U.S., though that assumes the country will continue to be under the control of an oil-friendly Republican administration.

The group has filed to become an official political party and will focus on electing candidates to push its agenda in Ottawa, Downing said. One of its primary targets is Jason Kenney, Alberta’s Conservative premier, who’s already created a provincial panel to consider such measures as withdrawing from Canada’s federal pension system, establishing Alberta’s own police force, and opting out of some federal cost-sharing programs. So far, he’s held out against holding a provincial vote on secession. “If he’s not going to give us our referendum, get out of the way,” Downing said, as the crowd cheered. “You’re going to be replaced.”

While splitting Alberta from the rest of Canada is unlikely, Wexit has helped make the province’s grievances a national priority. Trudeau last month appointed Jim Carr, a member of Parliament from Winnipeg and a former minister in his cabinet, as an adviser on western Canada. He also named Chrystia Freeland, his Alberta-born former foreign affairs minister, to the role of deputy prime minister, giving her latitude to work on soothing western alienation.

Trudeau addressed western Canadian alienation in a news conference shortly after his election, noting the economic challenges in Alberta and Saskatchewan, reiterating his support for the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, and saying he’ll continue working to help the prairie provinces. “We are moving forward to solve some of those challenges, but it’s going to take all Canadians sticking together, helping out folks who are struggling in places like Alberta and Saskatchewan,” the prime minister said. “This is what Canadians expect of their government, and this is something that we’re going to stay focused on.”

Brett Wilson, an entrepreneur and former judge on the Canadian business show Dragon’s Den, says that while he doesn’t necessarily want Alberta to separate from Canada, the Wexit movement strengthens the province’s hand in its dealings with Ottawa. “I’m having trouble finding anyone who says, ‘No, no, our current deal is fair,’” Wilson says. “What all of us want, and I think everybody at the table wants, is a deal that feels fair and is fair.”

Another key to subduing the separatists’ ire will be reviving Alberta’s oil industry. It was deeply wounded by the 2014 oil price crash, and growth has been hampered as pipeline capacity has failed to keep pace with production increases. Alberta’s unemployment rate has remained stubbornly high the past four years—clocking in at 7.2% in November, compared with 5.9% for the country as a whole—as the inability to expand keeps workers idle.

Still, the province produces 3.8 million barrels of crude oil a day, making it one of the world’s 10 largest oil-producing jurisdictions. All told, Alberta accounts for about 17% of Canada’s gross domestic product. “If we just turn the taps off, it’s going to make the east start asking us to help them out,” said Madison Lepard, a 28-year-old lawn maintenance worker, at the Wexit rally. “We’d be just fine on our own.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.