Al Gore’s Firm Leads $100 Million Investment in African Outsourcing Startup

Al Gore’s Firm Leads $100 Million Investment in African Outsourcing Startup

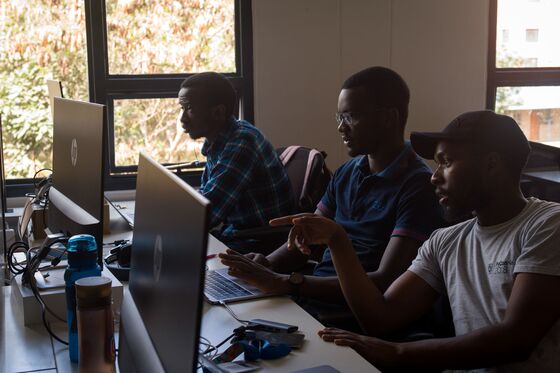

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Outsourcing isn’t generally seen as the most high-minded of industries. But when the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the philanthropic organization backed by the wealth of Facebook’s founder, looked to write checks to startups, the first investment it led was for Andela, which places African computer programmers to work remotely for American corporations. By training Nigerian computer programmers, the thinking went, Andela’s office in Lagos would speed the development of the technology industry in those countries. “Technology is the exact opposite of an extractive industry,” says Jeremy Johnson, Andela’s chief executive officer. “Success begets success.”

Andela now operates in Kenya, Uganda, and Rwanda, and has about 1,100 developers on staff working for more than 200 companies, nearly 90 percent of which are located in the U.S. Now former U.S. Vice President Al Gore’s sustainability-focused investment firm, Generation Investment Management, is leading a $100 million funding round in the outsourcer, bringing Andela’s venture capital haul to date to $180 million.

Generation’s interest in Andela parallels CZI’s—with the bonus, it says, that large-scale remote work could help reduce greenhouse gas emissions. “Remote collaboration, and allowing people not to get on planes, obviously has carbon benefits,” says Lilly Wollman, who led the Andela investment. She expects the company to be placing 10,000 developers with clients within the next several years.

Among the inevitable points of comparison for Andela are large Indian staffing firms such as Infosys Ltd., Wipro Ltd., and Tech Mahindra Ltd., which have grown into multibillion-dollar concerns by providing employers with low-cost programming talent. India’s IT companies have played a key role in the development of the country’s technology industry, but also have a reputation for handling mostly lower-skill projects. The businesses are controversial in the U.S., where critics accuse them of harming American workers by offshoring some work and abusing the H-1B visa program to undercut local wages.

Andela’s executives and investors distance themselves from the classic outsourcing model. “You don’t have to do what India did,” says Johnson. He says Andela aims to compete more on quality than on price. Its developers are more tightly integrated into the operations of their clients than traditional offshore workers, and hired for a set period of time rather than specific projects. When Andela workers start assignments with new employers, they travel to their headquarters for weeklong visits. Some of the company’s clients have even begun to bolster Andela workers’ compensation with equity stakes, a key perk of Silicon Valley employment.

The idea for Andela started with a Nigerian online education startup called Fora. Iyinoluwa Aboyeji, one of Fora’s founders, said the company was struggling to raise capital. So they reached out to Johnson, whose own company, 2U, was based on a similar idea. At a meeting in New York, the group came up with the rough idea for Andela. Aboyeji returned to Lagos to start the company in a vacant duplex that an acquaintance let them use for free. Johnson initially intended to be an investor and board member, but soon ended up becoming the startup’s CEO instead. (Aboyeji left Andela in 2016.)

Andela’s distinguishing factor, according to Johnson, is the software it uses to assess applicants, train them, and then monitor their performance once they’re on the job. Andela uses data it culls from its clients to determine which computing languages and development skills are most in demand. Its training regimen also focuses on soft skills, such as how to handle workplace Slack chatter. Once developers go to work, Andela’s software produces regular reports on things like how long it takes each developer to write 100 lines of productive code (eight hours on average), or how many days per week an employee is contributing code. In addition to the developers working for clients, Andela employs 400 people to build its own software and manage its business operations.

The Generation deal would be the third-largest venture investment ever for an African startup, according to research firm CB Insights. Andela’s status as an African company, however, is a matter of debate. CB Insights defines it as American, noting that its headquarters is on West 29th Street in Manhattan. Johnson says the company doesn’t really have a nationality. “If you ask where our headquarters is, I’d say the internet,” he says.

That answer doesn’t satisfy everyone in the African technology community. Critics in Lagos have complained that a Nigerian success story was erased with the arrival of Mark Zuckerberg and his money. “Now that the validation of Andela as a success is going global, Lagos has been reduced to one of the campuses of [a] New York-based startup,” Oo Nwoye, a prominent Nigerian entrepreneur, wrote in a 2016 essay.

Still, Andela is widely celebrated in Lagos. It accepts about 1 percent of applicants—a significantly lower rate than even the pickiest American universities—and its wages are generous by local standards. Developers who get into the program make four-year commitments to the firm, both to offset the cost of their training and because otherwise they’d become recruiting targets for foreign firms. Monicah Kwamboka, an Andela developer based in Nairobi and working at the American cybersecurity firm Cloudflare, says she plans to stay on even after her initial contract expires. “I feel like remote work is the future,” she says. “I see myself doing this for a long time.”

The attraction of skilled African developers to foreign employers extends beyond Andela, a dynamic with potentially negative local impact. Prosper Otemuyiwa, a former technical trainer at Andela, describes a common career progression for a Nigerian technologist. First, work at a local firm for relatively low pay while developing the skills to appeal to companies abroad. Then, either emigrate or find remote work for salaries dwarfing those available nearby.

Such patterns have put pressure on the Nigerian startups who were previously the only option for developers. “Before all the opportunities came by, the local companies were paying just local rates,” says Otemuyiwa, “and not just local rates, but poor local rates.” Johnson says Andela has highlighted an alternative to emigration.

Over the last year or so, Nigerian startups have significantly increased their own salaries and benefits packages, something they’ve been able to do in part because of an increase in foreign venture capital that successes like Andela have attracted. But Mark Essien, CEO of Hotels.ng, an online hotel-booking website based in Lagos, says international competition has made it harder for his company to attract local developers. “It’s tough to contain them at local jobs,” he says. “They go abroad or work remotely.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeff Muskus at jmuskus@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.