After Years of Easing, Meet Quantitative Tightening: QuickTake

When did quantitative easing turn to quantitative tightening?

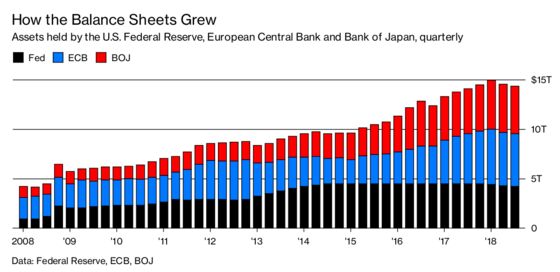

(Bloomberg) -- For a decade, investors around the world have ridden a rising tide of more than $12 trillion -- the extra cash pumped into the global system by key central banks to counter the deepest financial crisis since the Great Depression, and its aftermath. Now that flow of so-called quantitative easing is turning to the ebb of quantitative tightening, and markets are -- perhaps not coincidentally -- showing increasing volatility.

1. What’s quantitative tightening?

The easy answer is that it’s the opposite of quantitative easing, or QE. Milton Friedman had proposed a type of QE decades ago, and the Bank of Japan pioneered its use in 2001 after it had run out of conventional ammunition by lowering its benchmark short-term interest rate to zero. In QE, a central bank buys bonds to drive down longer term rates as well. As it creates money for those purchases, it increases the supply of bank reserves in the financial system, and the hope is that lenders go on to pass that liquidity along as credit to companies and households -- spurring growth. To avoid the impression that the central bank is just financing the government, it buys the bonds in the secondary market rather than directly from the Treasury or finance ministry.

2. When did QE switch to QT?

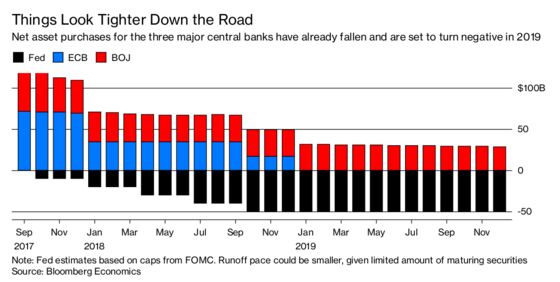

The U.S. Federal Reserve applied QE in force starting in 2008, buying up bonds to revive the flow of credit to a shrinking economy. It stopped increasing its stockpile of bonds in 2014, and now is shrinking its balance sheet. While the BOJ and European Central Bank are still in the QE business, they’re tapering their purchases. Their collective balance sheet peaked in March. Bloomberg Economics has declared this October as the month the world’s major central banks collectively started running down their bond holdings.

3. How does QT work?

The Fed is now letting as much as $50 billion of its bond holdings mature every month without replacing them. That takes money out of the financial system, as the Treasury Department then finds new buyers for its debt. The Fed describes the winding down of its balance sheet, along with rate hikes, as part of a “normalization” of its policy stance and a response to the solid performance of the American economy and a return of more-normal inflation rates. The ECB, BOJ and Bank of England were among the central banks that deployed QE and may at some point start shrinking their own balance sheets as the Fed is now doing.

4. How much QT has there been?

Since the ECB and BOJ are still buying securities, what’s happened so far is essentially a scaling back of QE, rather than an actual unwinding. But the shift has been enormous. A simple summing of the G-3 central banks’ balance sheet shows a drop of about $92 billion in 2018, through September. The same period of 2017 showed a jump of about $1.7 trillion, so that suggests roughly $1.8 trillion dollars’ worth of liquidity injection went missing from the markets this year. Balance sheets can be affected month-to-month by items other than just the QE programs, and exchange rates change, but the direction is clear. And the pace of change is set to accelerate: Not only did the Fed increase its monthly draw-down this quarter, but the ECB is scheduled to terminate QE by year-end and the BOJ has been opportunistically trimming its bond purchases.

5. How are the markets reacting?

There’s always debate on the causes of market declines. But the increased volatility seen across asset classes this year has occurred against the backdrop of the titanic shift away from QE. A global sell-off in stocks in late January and early February followed the ECB beginning to taper its bond purchases. As the Fed drew down its Treasuries holdings and kept raising rates, yields climbed, putting particular strains on emerging markets by late April. And the October slump in equities across the world came the same month that the collective central bank bond portfolio started shrinking. The Fed’s rollback has helped propel a strengthening in the dollar, putting yet more strain on borrowers in developing nations with debt obligations in greenbacks.

6. Is there disagreement about QT’s impact?

Absolutely. To some market observers, the main point is still how accommodative the central banks still are. Even as they stop, slow or reverse their buying of bonds, Bank of America Corp. reckons, the combined balance sheet of the Fed, ECB, BOJ and Bank of England will be just 4 percent smaller by the end of 2020. That means plenty of liquidity left sloshing around the global financial system and supporting the world economy.

7. Who are the winners and losers of QT?

The assets that were QE winners are QT losers and vice-versa. While longer-dated Treasuries have enjoyed historically low yields for the better part of a decade, JPMorgan Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon, for one, has warned of 10-year yields climbing past 4 percent, from less than 3.5 percent now. His bank has estimated that bond issuance skewed toward lower-rated companies and longer-dated securities in the QE era. Investors in money markets are big winners. They’ve gone from earning next-to-nothing to drawing more than 2 percent. The stronger dollar means that emerging markets in particular are facing strains, as investors worry about the ability of developing countries to pay off their dollar-denominated debt.

8. Does anyone think this is a bad idea?

Yes. While U.S. President Donald Trump has focused his criticism on the Fed’s interest-rate hikes, he made clear during the Oct. 10-11 stock slump that he wants the central bank to hold off on tightening. Emerging market countries have also called for the Fed to be mindful of the ramifications of its normalization campaign. The finance minister of Indonesia, the world’s fourth most-populous nation, said in October that spillover effects from the Fed are “very real for many countries.” India’s central bank governor wrote a newspaper column in June warning a “crisis” in dollar funding will be inevitable if the Fed doesn’t ease off on QT. In Europe, populist political parties may agitate against the ECB drawing down its holdings of debt and -- by extension -- potentially pushing up government borrowing costs. Some Fed officials have called for discussion about bringing an earlier end than anticipated to the balance-sheet contraction, after some signs of tightness in the market for overnight cash.

The Reference Shelf

- Milton Friedman’s 1968 essay in which he proposes a policy similar to QE.

- QuickTake explainers on the Fed’s unwinding and how central banks shrink their balance sheets.

- A Bloomberg Economics brief on the shift from QE to QT.

- Bloomberg Opinion’s editorial on QT and the resulting volatility.

- The Guardian’s explainer on how QE works.

- A Brookings Institution article on shrinking the Fed’s balance sheet by former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke, who directed its buildup.

To contact the reporter on this story: Christopher Anstey in Tokyo at canstey@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Zoe Schneeweiss at zschneeweiss@bloomberg.net, John O'Neil

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.