After World Cup Success, Women’s Soccer Aims for the Big Leagues

After World Cup Success, Women’s Soccer Aims for the Big Leagues

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When Manchester City and Manchester United kicked off the English women’s soccer season on Sept. 7, the crosstown rivals took the field before a crowd of 31,000. That afternoon, Bristol City traveled to Brighton for a match in the 27,000-seat Ashton Gate Stadium, and the next day Chelsea took on Tottenham at Stamford Bridge in London, where more than 24,000 fans showed up, a DJ spun tunes, and brunch was served to those who paid an extra £60 ($74).

But this coming weekend, the teams will return to the more modest digs where they play the bulk of their matches—many tickets for opening day were given away for free—and they’ll be lucky to get more than a few thousand spectators.

With the resounding success of the World Cup this summer, women’s soccer is hoping for a resurgence worldwide. The four-week tournament packed stadiums across France while millions of fans tuned in on TV, and the victorious U.S. squad was feted with a ticker-tape parade in New York. For the nine-team National Women’s Soccer League in the U.S., the attention has led to record turnout for early-season matches and new partnerships with ESPN and brewer Anheuser-Busch InBev. In Brazil, the biggest sports channel will broadcast a women’s league match every Sunday, and Uber Technologies has signed up as a sponsor. Spain’s Real Madrid—the club that transformed the men’s game by spending lavishly on superstars—has bought a women’s team and is scouring the globe for top talent.

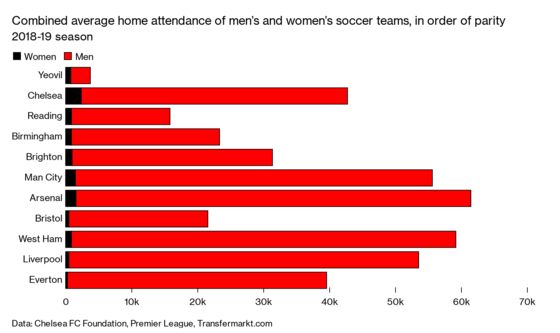

Still, by virtually any measure, soccer’s women trail far behind their male counterparts. In England, matches among the dozen teams in the nine-year-old Women’s Super League last year averaged just 996 spectators. Although the clubs expect to double attendance this year, they’ll still attract less than 5% as many fans as the men’s Premier League does. And many women’s clubs operate in the red: Chelsea says its women lost more than £700,000 on revenue of £3.5 million in the year ended June 2018.

For the game to really take off, clubs must get serious about boosting salaries, says Rebecca Smith, a former player for the New Zealand national team who’s now an executive director at Copa90, a producer of soccer videos. The U.S. women’s success in France prompted calls for the players to earn as much as the men’s national team, which failed to qualify for the World Cup last year, let alone win it. At the club level, the difference is stark: WSL players take home about 1% of the £2.6 million average salary in the Premier League, according to researcher Sporting Intelligence. France’s women get roughly €42,000 ($46,000), about 4% of what the men do. In Mexico the average is a bit more than $2,000 per season, 0.5% of the men’s wage.

Just as important, Smith says, is greater respect for female players. Santos, a top Brazilian women’s team, in July had to sleep in a hotel lobby while traveling to an away game because no one remembered to book rooms—the sort of blunder that would never happen to a men’s team. And the Chelsea women’s home of Kingsmeadow, a 30-minute drive from the men’s venue, seats fewer than 5,000. Shifting more matches to the main stadium would “show the world that the club knows the women’s team deserves to play there,” Smith says.

One standout is France’s Olympique Lyonnais, which has won the European women’s Champions League a half-dozen times. Although the women’s budget remains a fraction of the men’s, Olympique players of both sexes share training and medical facilities, and the women play several matches each season at the club’s 59,000-seat primary stadium. Most important, women’s salaries average more than €50,000 a year. “We can ride the wave of the World Cup,” says Olympique President Jean-Michel Aulas. “When it comes to endurance and teamwork, women’s football has caught up with men’s.”

The easiest way to boost salaries would be to increase revenue—from sponsorships, ticket sales, merchandising, and TV exposure. The Premier League earns more than £3 billion annually from broadcast rights for the men’s games, whereas women’s leagues take in a tiny fraction of that: The Spanish league has a €3 million-per-season rights deal, and the WSL in September announced an agreement to show matches in Latin America and Scandinavia, but it will receive less than £1 million per season. “The challenge is to work with the clubs to make them and the women’s game sustainable,” says Kelly Simmons, who oversees women’s pro teams at the Football Association, which governs the sport in England. “We are not there yet.”

More broadcasts would help raise the profile of female players, which could increase jersey sales and endorsement contracts. Clubs might also do more promotions that include both their women’s and men’s teams. U.S. bathroom-fixture manufacturer Kohler says it wanted a team that embraces diversity and inclusion when considering a soccer sponsorship. In the end, the company signed with Manchester United, and “the women’s club was the deciding factor,” says Chief Executive Officer David Kohler.

A publicity stunt along the lines of Billie Jean King’s 1973 tennis match against Bobby Riggs could give the sport a lift. In that contest, dubbed “The Battle of the Sexes” and broadcast live during prime time, King (29 at the time) beat Riggs (55), helping boost the profile of women’s tennis. While the greater physicality of men’s soccer would make a full match difficult, a penalty-kick shootout—where the emphasis is on technical skill—could work, says Vincent Chaudel, a sports consultant in Paris. “Women’s soccer needs to raise awareness around big personalities,” he says.

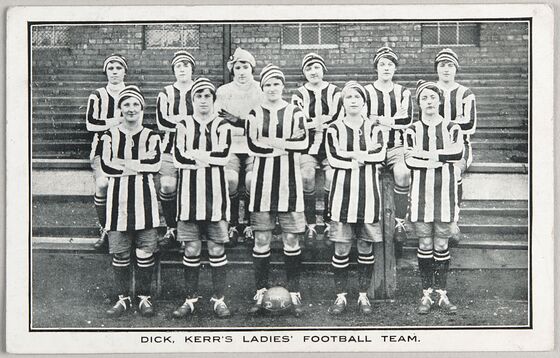

There’s a strong precedent for the game’s success. A century ago, women’s soccer was hugely popular in England as munitions factories set up teams to fill in for men fighting in World War I. In 1920 a match in Liverpool between Dick, Kerr & Co. and St. Helens Ladies drew 53,000 paying spectators while an additional 14,000 people queued outside, unable to get in. The following year, concerned that soccer wasn’t suitable for women, the Football Association barred women’s teams from big stadiums. While the restriction was finally lifted in 1971, the sport has struggled to recapture the magic it enjoyed a half-century earlier. “The ban created cultural norms that have only recently started to change,” says Izzy Wray, a consultant in Deloitte’s Sports Business Group. “It’s vital that we not lose the buzz of the opening weekend.” —With Mario Sergio Lima and Eben Novy-Williams

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rocks at drocks1@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.