The Ticking Debt Bomb in Africa Threatens a Global Explosion

Africa’s Debt Will Be the Next Explosion

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The new airport serving the Angolan capital of Luanda was intended to be a bright and welcoming symbol of the former Portuguese colony’s renaissance—a counterpoint to the three-decade civil war that ended in 2002. Two parallel runways were to accommodate even the biggest jets, a new 40-kilometer (25-mile) rail line would whisk passengers to the city center, and a shimmering glass terminal bigger than the Pentagon was designed with dozens of restaurants, bars, and shops for the 15 million visitors the government expected to pass through annually.

Sixteen years after construction crews broke ground, the terminal—largely completed in 2012—is gathering dust in the flat scrubland southeast of Luanda. The railway was never finished, the runways have yet to see a commercial flight, and the opening date has been repeatedly pushed back—now expected sometime in 2022 or 2023. What’s harder to push back, though, is the billions of dollars in loans that funded construction. While the government hasn’t revealed the financing details, local media estimate that Angola owes Chinese creditors from $3 billion to $9 billion for the unfinished facility.

The Luanda airport is just one of hundreds of megaprojects that have supercharged African economies over the past decade. Angola alone has built Kilamba, a satellite city outside the capital that’s home to 80,000 people, two other airports, a state-of-the-art library that was abandoned halfway through construction, and four soccer stadiums seating as many as 50,000 spectators. Across the continent, governments have spent at least $77 billion annually since 2013, erecting everything from critical infrastructure such as bridges and hospitals to sumptuous presidential villas and soaring monuments celebrating national heroes.

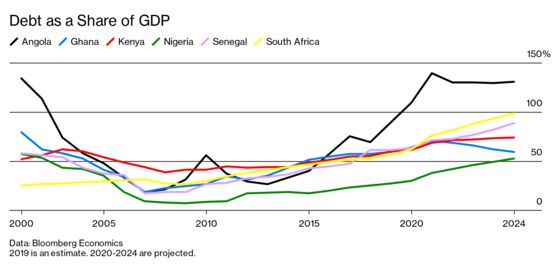

The building binge has been fueled by at least $600 billion in loans, leaving African governments struggling with record debt. The obligations were manageable—barely—when countries in the region were expanding by as much as 10% annually. But with the coronavirus pandemic shutting down trade and hammering commodity prices, the debt bill threatens to unravel years of progress in fortifying economies and fighting poverty. After 25 years of uninterrupted growth, the region this year will contract by 2.8%, the World Bank predicts.

The coronavirus has created “the biggest shock the global economy has faced over the last century,” Charles Calomiris, a professor of public affairs at Columbia, said at a World Bank web meeting on June 1. And rapidly expanding debt loads in developing countries, particularly Africa, will only magnify the difficulties. “I’m scared to death,” he says. “The risks associated with this protracted and severe crisis coming from the unpayable debt problem are going to be unprecedented.”

Public debt, which had doubled to about half the continent’s economic output since 2008, was raising alarm bells at the International Monetary Fund even before the Covid-19 pandemic. The IMF says more than a third of African countries are approaching or already experiencing “debt distress” after a slowdown in commodity prices in 2014. Today, fallout from the pandemic makes the easy money of a few years ago an unbearable burden as the outbreak threatens to overwhelm hospitals already stretched thin by illnesses such as malaria and tuberculosis. “Our leaders have two choices: You either pay obligations to bondholders or you buy medicine, food, and fuel for your population,” says Vera Songwe, head of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa.

Africa’s struggle is becoming a global problem as the money has come from a China seeking to bolster its influence in the region and from global investors hungry for returns in a world awash with negative yields. African governments have sold almost $60 billion in bonds to private investors in the past two years to pay for highways, factories, and wages for their sprawling bureaucracies.

A flurry of defaults would threaten the newfound prosperity that the debt buildup helped bring about. Booming economies have reduced poverty to the lowest levels since the 1990s and ushered in a new middle class. Multinationals selling everything from cellphones to soda raced to tap a market of more than 1 billion consumers. But the UN predicts the coronavirus could add an additional 29 million people to the more than 400 million Africans living in extreme poverty.

The problems could be even more damaging than the region’s last debt blowup, in the late 1990s—a hangover from borrowing that dated to the early ’60s, when newly independent African countries spent lavishly on infrastructure and social programs to forge national identities and modernize their economies. In 2005 wealthy nations and financial institutions agreed to write off $100 billion in loans, but the cost to the region was high: currency devaluations that fueled hyperinflation and austerity programs that forced steep cuts in social spending.

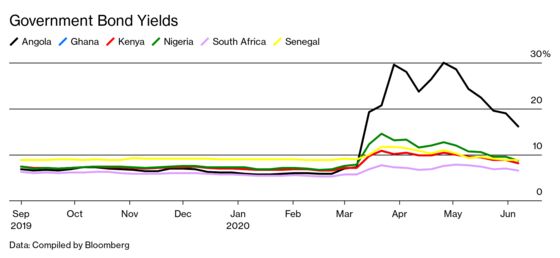

Some investors say the fears of a debt bomb are overblown and are betting the economic fallout of the pandemic in Africa will be relatively mild. Yields on bonds from Sub-Saharan Africa have dropped to an average of about 9% from almost 13% in May, indicating that investors are more optimistic about getting repaid. Those lower yields mean governments may be able to raise funds in coming months even as their revenue plummets. And a recovery in prices for oil and minerals will help exporting countries.

But many academics have begun comparing the looming debt crisis in Africa to the sovereign and corporate defaults that engulfed Latin America following an influx of petrodollars in the 1980s. That calamity led to years of economic turmoil in what became known as the region’s lost decade as countries starved for cash suffered recurring defaults to international banks. “African growth will be stopped in its tracks,” says Patrick Bolton, a professor of business at Columbia. “The way things are playing out, there will likely be difficult debt restructurings ahead.”

Carmen Reinhart, incoming chief economist at the World Bank, predicts that any recovery will be slow and fraught with tension. Most debtor countries require multiple overhauls to stabilize their economies, and negotiations with private creditors typically drag on for four years or longer. “The restructuring process has this long back-and-forth,” Reinhart said at the June 1 World Bank web conference. “I look at the restructurings of the 1920s and 1930s, and of the 1980s and 1990s, and what I see is a decade-long process.”

The share of African government revenue that goes toward external debt service has almost tripled, to an average of 13%, in the past 10 years, according to the Jubilee Debt Campaign, a London group that advocates relief for poor countries. That’s more than governments in the region spend on health care, and the cost of paying off loans is poised to climb further as economies shrink and local currencies weaken. That, in turn, threatens to divert scarce resources from infrastructure projects needed to fuel a recovery.

The risk is greatest in countries highly reliant on sales of a single commodity. Zambia, which gets 70% of its foreign exchange from copper exports, has seen its external government debt jump sevenfold in a decade, to more than $11 billion. In May it appointed a financial adviser to restructure its obligations. The IMF predicts that debt service in Angola, Africa’s No. 2 oil producer, this year will cost more than the government’s total revenue, and the Finance Ministry has contacted China about rescheduling some loans.

To stave off economic collapse, 25 African finance ministers in March wrote a letter to global leaders asking for delays in $44 billion in debt payments due this year while they focus on fighting the virus. In response, the Group of 20 leading economies proposed an eight-month suspension of payments—totaling about $11 billion—from 73 of the world’s poorest countries, most of them in Africa. But progress has been slow, and only 12 countries have gotten a waiver so far.

The G-20 governments have called on multilateral lenders to join the moratorium, but that may be difficult. The World Bank and other development banks, which hold about a third of sub-Saharan Africa’s external public debt, say a suspension threatens to tarnish their own credit score; Fitch Ratings Inc. has said a repayment freeze could spur a downgrade for development banks unless shareholders compensate them for losses. As an alternative, the World Bank has offered to accelerate delivery of tens of billions of dollars in loans to developing countries.

Private creditors have also been reluctant to join any suspension, insisting that revamping contracts could trigger credit downgrades and end up raising interest on new debt that governments will need to bounce back from the pandemic. And asset managers and banks that own almost half the continent’s outstanding external debt say legal commitments to clients make a blanket waiver impossible. As a workaround, some investors have raised the possibility of advancing cash to governments to pay obligations this year.

Daniel Munevar, a policy adviser with the nonprofit European Network on Debt and Development, says such a plan would simply postpone the problem rather than solve it. What the lenders are proposing, he says, is shoveling more debt onto the pile, which will create greater trouble down the road. “It is unconscionable that private creditors are effectively requesting terms that will add to the long-term debt burdens of developing countries,” says Munevar, who worked with the Greek finance ministry during its debt crisis in 2015.

Even some African countries are having second thoughts about seeking help. They fret that delays in repayment—and the likelihood of a negative reaction from ratings companies—could lock them out of debt markets for years. They’re right to be concerned: Moody’s Corp. said it was reviewing the credit scores of Ethiopia and Pakistan after they simply expressed interest in seeking a pause in debt payments (they later applied, and on June 9 they were granted relief).

A bigger challenge may be renegotiating payments to Africa’s biggest creditor, China. In recent years, China’s lending—mostly unreported—has grown to exceed the combined loans of the IMF, World Bank, and the Paris Club (a group of 22 countries that lend to developing nations), according to the Kiel Institute for the World Economy. Africa has borrowed as much as $150 billion—almost 20% of its external debt—from China, data collected by Johns Hopkins University show. China says that as part of the G-20, it will do its share to ease Africa’s debt burden, but it hasn’t announced details, and the conditions of many of its loans are murky. In the past, China has offered relief but in return has demanded control of prized state assets such as ports or mines. “The terms of these loans are very opaque and will take a lot of time to restructure,” says William Jackson, chief emerging markets economist at research firm Capital Economics Ltd. “There is little negotiating power among African countries. China is in a stronger position.”

Ghanaian Minister of Finance Ken Ofori-Atta says the entire debate places unfair pressure and untenable burdens on his region. While the U.S. and Europe earmark trillions of dollars to jump-start their economies, rescue failing companies, and ease the pain the pandemic is visiting on their citizens, global lenders are demanding that Africa pay its debts on time. Ofori-Atta, a former investment banker with Morgan Stanley in New York, is seeking a three-year suspension of loan payments and says Africa risks tumbling into a depression without it. “The Western world can print $8 trillion to support their economies in these extraordinary times, and we are still being thrown a classical book with classical responses,” Ofori-Atta said at a Harvard web conference on June 3. “You really feel like shouting, ‘I can’t breathe.’ ” —With Candido Mendes and Matthew Hill

Read next: China Blew Opportunity to Lead During Coronavirus Crisis

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.