Afghanistan’s Economy Is Collapsing as Cash Disappears

Afghanistan’s Economy Is Collapsing as Cash Disappears

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Just weeks after the last U.S. troops left Afghanistan, a cash crisis has crippled its already feeble economy.

The tight supply of money, as well as border restrictions and increasing international isolation, is leaving workers unpaid, forcing local companies to shut and banks to limit withdrawals. It also threatens to cut off Afghanistan from the outside world, as wireless carriers struggle to pay suppliers. More worryingly, the situation is worsening food shortages and driving the cost of essential goods higher, setting the stage for a wider economic and humanitarian crisis.

During the 20-year U.S. occupation, Afghanistan’s economy was propped up mainly by international aid and U.S. dollars, which circulate alongside the local currency—the afghani—and are used regularly to pay for imported goods and services, as well as in big-ticket transactions such as buying a home or paying private school tuition. Shah Mehrabi, a board member of Afghanistan’s central bank who’s now in the U.S., estimates that dollars accounted for about two-thirds of deposits in the banking system and half of all loans. “Dollarization is still prevalent in Afghanistan, and our economy depends on it,” he says.

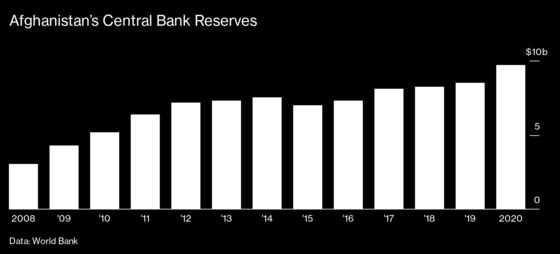

The issue is that the U.S. and others haven’t recognized the Taliban as the legitimate authority in Afghanistan, because of concerns about their involvement in terrorism and human-rights abuses. The country’s new rulers lost access to more than $9 billion in central bank reserves after the Biden administration froze assets held at U.S. banks in mid-August, with other countries following Washington’s lead. Funding from the Word Bank and the International Monetary Fund is also on hold.

To conserve what little reserves are left, the Taliban have resorted to capital controls, including barring Afghans from taking dollars out of the country and limiting bank withdrawals to $200 a week. In Kabul, some residents are selling furniture and other household goods at flea markets to raise cash. “The liquidity crisis is worsening, and many banks aren’t able to pay depositors,” says Ahmad Khesrow Zia, the former chief executive officer of Bank-e-Millie Afghan—the nation’s oldest bank—and now an economics professor at a private university in Kabul.

Small- and medium-size enterprises flourished in the years after the Taliban was ousted in 2001, increasing their role in Afghanistan’s $20 billion economy, according to the World Bank and the country’s chamber of commerce. Now they’re at risk of extinction. “If these companies collapse, the whole nation’s economy collapses,” says Khanjan Alokozay, a senior member of Afghanistan’s chamber of commerce, noting that several have already suspended operations due to lack of cash.

Haleem Gul, an auto mechanic in Kabul, says almost none of his customers have money to pay for repairs. “Cash has absolutely vanished,” he says. Jawed Mehri, who runs a rug factory in the northern city of Mazar-e-Sharif, says he had to halt operations because there is no cash to pay salaries. The withdrawal limits “may help banks to run for some time,” he says. “But it will kill our business and probably everyone else’s along the way.”

A report published last month by the United Nations Development Programme says that in the worst case, gross domestic product could decline 13.2% in the fiscal year that ends June 2022. That would send almost the entire population of 38 million into poverty, from about 72% in 2020.

“This is really a drastic situation,” says Abdallah Al Dardari, the UNDP’s resident representative in Afghanistan. A collapse in the national economy, he says, “is not where things are going. This is where things are now.”

The UNDP report also warned that food insecurity was “rising precipitously” because of declining output, higher prices, and import constraints. Prices for some staples, such as rice, cooking oil, and flour, have increased by as much as 30% since the Taliban took over, according to data from the Kabul Retailers Association. The World Health Organization also recently warned that the country’s health-care system is teetering because of the cuts in donor funding.

The Taliban haven’t attempted to downplay the severity of the situation. “If the public funds remain frozen or aid remains halted, the country could experience a worst-case economic crisis, forcing local companies that provide jobs to collapse,” Bilal Karimi, a Taliban spokesman, told Bloomberg News on Sept. 29. According to Karimi, the Taliban hasn’t been able to pay government salaries since assuming control. “Our financial team at the Finance Ministry is working day and night,” he said, adding that lower-level employees might be getting wages “in the near future,” while higher-paid employees, who get salaries in dollars, will likely see a “significant reduction” in pay.

Reached again on Monday, Karimi said a solution to the cash crunch is near, but “some technical issues remain,” without providing further details.

The Taliban had earlier said revenue from customs duties was enough to cover public-sector salaries. Yet it’s unclear how far they can stretch funds from other revenue sources, including mineral exploitation and tax collection, without having to fall back on extortion and kidnapping for ransom, as well as production and trafficking of illegal drugs—activities that supported the movement during the U.S. occupation.

Poppy-based drugs and methamphetamines were the “Taliban’s largest single source of income,” according to a UN report from June. Upon the Taliban’s assuming power in August, spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid promised that the new regime was not about to turn Afghanistan into a narco-state. “We are assuring our countrymen and women and the international community, we will not have any narcotics produced,” he told reporters.

International organizations and governments have begun providing assistance, motivated in part by the desire to avert a mass exodus of Afghan refugees. The UN in September announced $1.2 billion in emergency pledges, while the U.S. has granted sanctions exemptions for humanitarian organizations. China, which has criticized the U.S. freezing funds, will give $31 million in emergency aid. But this will only go so far in a country where external aid accounted for about 75% of public spending in recent years.

Bismillah Zakeri, who left his job an administrator in the Ministry of Education before the fall of Kabul, has taken to selling his family’s belongings on the street to raise money for food and to fund his planned journey to neighboring Pakistan. “What else can we do to survive?” he says. “If the hunger doesn’t kill us, the fear, anxiety and depression because of the Taliban regime definitely will.” —With Ismail Dilawar

Read next: Central Bank Autonomy Faces Challenges in Three Emerging Markets

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.