Luxury Trips to Meet Remote Villagers Can Come at a Cost

In Search of Raw Authenticity on an Adventure Cruise to West Papua

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Felix Wom, chief of the Asmat village of Syuru, looked intimidating in his grass skirt and fur headdress, bird feathers protruding from the side. A necklace of sharp animal teeth stretched across his bare, muscular chest, and his nose held a large curled ring. This ornament was made of seashell, but in the past it could have been carved from human bone.

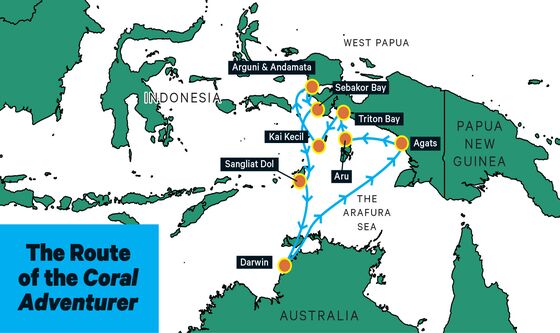

Twelve miles off the sparsely populated south coast of the Indonesian province of West Papua, Wom sat, unsmiling, for the first time on the deck of a cruise ship. The 120-passenger Coral Adventurer was on an inaugural voyage to West Papua, which encompasses most of western New Guinea and other nearby islands, and the ship’s captain had invited Wom and a handful of other village elders onboard to calm any fears about intruding foreigners. He offered them a look around, hats with baseball logos, and tins of butter cookies to take home.

“They want to have a peek at us and really want to see the ship,” says tour lecturer Kathryn Robinson, a retired anthropology professor at Australian National University whose research focus includes Indonesia. “If you say no, because that would make us feel uncomfortable, that doesn’t work. … Hospitality is a big thing in Indonesia.”

The chief already understood it—the symbiotic relationship between locals and visitors. “We can keep our culture because people come to see it,” he said through a translator, acknowledging the importance of the money the cruise line brings to his village. “We would be very happy to have more ships coming.” As I walked away from our chat, the chief raised his chin, looked ahead at nothing, and let out a long rhythmic call.

The Asmat people once were known as great warriors who used headhunting and cannibalism in their warfare, cultural rituals that ended for good about 60 years ago with the arrival of the Indonesian government. Photographer and art collector Michael Rockefeller, one of Nelson’s five sons, may have been a victim of cannibalism after his boat overturned near an Asmat village in November 1961, according to the book Savage Harvest, by Carl Hoffman. His body was never found.

The culture lives on in part through performance—which is how the government likes it, says Stuart Kirsch, a professor of anthropology at the University of Michigan who specializes in the Pacific region. “When you’re not there, they’re wearing Rolling Stones T-shirts from the global used-clothing market, cutoff jeans, and worn-out flip-flops,” Kirsch says. West Papua has an independence movement, he says, but “that’s typically scripted out of the tourist narrative.”

Add the navigational difficulties of swirling winds, shallow seas, shifting sands, and multiple reefs, and it’s no wonder travelers seldom stop by. That our diesel-electric vessel was here, near the equator in the middle of hot nowhere, is a result of the expanding market for expedition cruises. Such small-ship travel has drawn particular interest among baby boomers willing to pay fares that often top $1,000 a night for meaningful soft adventure experiences in hard-to-reach destinations.

In this growing niche of the cruise market, 39 expedition ships are set to make their debut from now to 2024, according to Cruise Industry News. Big cruise companies are dipping their toes into the lucrative arena. Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd. acquired four expedition ships (as well as five ultraluxury ships) last year when it paid about $1 billion for a two-thirds stake in Silversea Cruises Ltd. “It probably increased their fleet capacity by 2% but increased their profit flow by 6%. The profit per ship is that much higher,” says Bloomberg Intelligence senior analyst Brian Egger.

Most of the new boats are polar-class vessels bound for popular cold places such as Antarctica, Iceland, Greenland, and the Canadian High Arctic. But other cruises are sticking to the tropics. As a result, some of the most isolated people on Earth are seeing more visitors.

Wom’s village of Syuru, with its rustic houses and boardwalks crossing the swamp, will welcome four shiploads of cruisers this year, a number agreed upon by the government and tribal representatives. Timing is important in the expedition business: The May itinerary of our round-trip cruise from Darwin, Australia, was tweaked so we could beat a ship owned by French line Ponant SA by a day.

We arrived early in the morning after two sea days churning north from Darwin. Passengers boarded the ship’s two hop-on, hop-off tenders and passed mangroves along a brackish river on our way to the village. As we approached, dugout canoes from several clans emerged from shore. Athletic men and young boys paddled from a standing position, most in grass skirts, their faces and bodies covered with war paint, which assures the warriors their ancestors will protect them.

Men reached for the sides of our boats. Paddles thumped against wood in unison with war cries. “They are performing themselves as violent people,” Robinson said. “They are saying, ‘This is who we are.’ ” If they were trying to look scary, they succeeded with me, especially as the flotilla increased to dozens of canoes.

Onshore, men performed a traditional ceremony to launch a new canoe. It was a frenzy of hip-swinging dancing, raised spears and shields, chanting, yelping, and drumming. Women in grass skirts, some topless, danced in support. Passengers stood on the edge of the ceremony, the action only somewhat diluted by some of the villagers holding cellphones. They were taking pictures of us, as we were of them. And what a sight we were in our “adventure” wear, sun hats, and sunglasses, slathered in sunscreen and bug spray. I hadn’t thought of myself as a cultural attraction, but locking eyes with a half-naked elderly woman, I realized we both were probing another world. I felt out of place in this one.

Cruisers pulled out rupiah to purchase Asmat art, which is sought by museums and collectors around the world. (Rockefeller was seeking pieces for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection of primitive works when he disappeared.) The art traditionally tells the stories of ancestors, but when I picked up a figurine for about $15—some works went for quite a bit more—and asked about its symbolism, the shy artist said it was just something he imagined.

Oswald Huma, a tour agent from the island of Savu, west of Timor, was hired by Coral Expeditions, based in Cairns, Australia, to help map out our “Warriors and Wildlife” itinerary. He said the most common question the villagers ask is, “Why do these people come to see us?” He struggles with the answer, usually replying that travelers want to buy the wood carvings. He doesn’t want to mention the attraction of a history of headhunting.

Robinson says the interactions bring much-needed income. She’s noticed that, since she first visited the Asmat a few years ago, conditions seem to have improved. “The way I see it, for these people who are miles away from any of the circuits of capital, tourism is helping them to realize that they do have something the world will buy, which is their culture,” she says. “We might have anxieties about it. But all through Indonesia, people hope that tourism is going to bring income into these remote areas. These people are separate from the exigencies of the world. Pristine and untouched has also got its negatives.”

The visits also provide the Asmat an opportunity to practice their culture, Huma says. Elders traditionally teach youth the group’s customs by performing ceremonies; paying customers are an excuse to do so. Kids also see the outside world and have an opportunity to practice English, “so they can go out and seek employment and send money home,” he says.

“It’s like anywhere where people are performing their culture,” says Kirsch, the Michigan professor. “It can be uncomfortable, but it can also promote mutual recognition. The Asmat are well known for their art, and these encounters can stimulate appreciation for the artistic style.”

Agats, a larger town we visited nearby, has imported goods for sale to locals. Among them are rice, which isn’t a staple of the Asmat diet but has become popular, as well as electric motorbikes, tea, sugar, and cellphones. Given the spotty signal, the phones are mostly used as cameras and for playing music.

Huma had spent months in his boat on the Arafura Sea south of West Papua, sometimes in rough seas, convincing leaders in remote villages to welcome the Coral Adventurer. He also arranged for English speakers to meet us at each of four stops. Many are teachers, and some traveled far for the jobs as guides.

In the village of Sangliat Dol, on Yamdena Island in the province of Maluku, the push and pull of multiculture life was magnified. During a one-hour bus ride beforehand, our guide said, “Visitors are rare, as it destroys the daily life.”

We were met by an enthusiastic crowd of costumed women in embroidered white peasant blouses and sarongs. Some had arrived hours earlier from nearby villages to greet us with a dance in which they waved scarves and small towels. They welcomed us as “sons and daughters of the village.”

A smiling older woman grabbed my arm, and to the accompaniment of drums and singing, the crowd danced past tin-roofed homes to a megalithic ceremonial stone boat in the village center. Shouting, shoving, even screaming ensued, and cruise passengers were hustled off to the side.

Seating in the boat is based on status, but it can be contested. A man had taken a position someone else felt was his. Government officials moved the arguing men out of view so a smaller group could perform a planned ceremony honoring our ship “elders.”

The fight—with yelling and shoving—was the rawest experience of our cruise. But for the locals, there was a price to be paid. A government official threatened to file a report, saying there would be consequences. Our ship withheld bags of school supplies, soccer balls, and clean sheets and towels for the health clinic, similar to gifts we’d delivered to other villages. The donations to Sangliat Dol returned with us. “We don’t know when we left the village if they would fight over a soccer ball,” Huma said. “We don’t want a bad thing to happen.”

No one on The Coral Adventurer, not even the captain, had sailed the West Papua itinerary before, a route designed to mimic a portion of Dutch explorer Abel Tasman’s voyage roughly 375 years ago. Coral Expeditions, a 35-year-old company owned since 2014 by Kallang Capital Holdings Pte. of Singapore, is known more for its cruises of Australia’s Kimberley region and the Great Barrier Reef.

When you commit to an expedition cruise to a remote locale, you can expect long days at sea getting there. Wi-Fi connections are sporadic, and there’s no satellite TV. Lectures are the main shipboard activity. A marine biologist prepared us for the world’s largest fish, whale sharks—who apparently didn’t get the memo about our arrival. We looked for them without success in Triton Bay in the southwest corner of West Papua. The passengers, mostly Australians over 60, relaxed onboard in modern cabins and lounge areas accented with African wood and Italian marble. Hot water flowed from showers, cappuccinos from coffee machines. Dinner was a three-course affair, with Australian wines.

It was sticky and hot when we explored the tidy dirt streets of the Muslim village of Arguni (population 227), in the Fakfak regional district. Women, their heads covered, and their grandchildren offered warm but cautious smiles. Most of the village’s adults were as far away as Bali and Jakarta for work or study. Although it was Ramadan, women had risen early to prepare fish dishes and cakes made of tapioca.

“You are not tourists anymore, but part of our family,” King Hanafi Paus Paus told the crowd. Later, in his small house, where the front room is furnished with plastic patio chairs and the walls are decorated with photographs of his forbears, the king said tourism is improving. Another ship had arrived five months ago. Ships have a “good effect,” he said through a translator. “It protects the history, plus we get money. People leave for work, and now work comes to us.” The king’s two sons are in high school in the town of Fakfak about 30 miles away. He goes there in his boat, then uses a car he keeps in town to get around.

In all the villages, locals attempted a few words of English, and there was a warmth and sincerity to our encounters—even if most amounted to us staring at them and them staring at us.

Ngilngof village, on Kai Kecil Island, provided the welcome that felt most linked with the outside world: Women in bright purple jackets and long gold skirts danced with delicate hand movements as a ritual leader in black raised a coconut, invoking ancestral protection for the island’s natural resources. Meanwhile, on a 3-mile-long beach with soft, white sand, plastic chairs were set up under a tent you could rent for the afternoon. Snack bars sold cold beers and Diet Cokes.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Chris Rovzar at crovzar@bloomberg.net, James Gaddy

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.