Police Reform Means Better Cops to Some, Fewer Cops to Others

Police Reform Means Better Cops to Some, Fewer Cops to Others

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- “We need to stand up and say that black lives matter,” Mitt Romney, one of Utah’s Republican senators, declared on June 7 as he marched in Washington with a crowd of thousands protesting police brutality against black people. Days earlier, in a photo with community leaders in Wilmington, Del., presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden took a knee—a symbolic gesture of support for protesters’ demand to end police abuses.

Gestures are one thing; actions are another. After the killing of George Floyd, a black man, by a white Minneapolis police officer on May 25 spawned nationwide protests, politicians are scrambling to respond with proposals to curb the power of the police. But the means by which they would do so differ starkly.

At the federal and state levels, measures focus on reform: strengthening rules around misconduct and bringing more accountability and transparency to police departments.

On June 8, Democrats on Capitol Hill introduced a sweeping bill that could make it easier to prosecute and sue law enforcement officers. The Justice in Policing Act would tighten the definition of criminal misconduct for police, establish a national misconduct registry, and require state and local law enforcement agencies to report disaggregated use-of-force data, among other measures. The bill would also curtail qualified immunity, a legal defense that helps police officers evade lawsuits for civil rights violations. (Four days earlier, Michigan Representative Justin Amash, a Libertarian, and Massachusetts Representative Ayanna Pressley, a Democrat, had introduced their own bill to end qualified immunity.)

Such expansive police reform in Congress has a rocky path forward, but Senate Republicans led by South Carolina’s Tim Scott are working on their own more limited set of proposals. White House spokeswoman Kayleigh McEnany said on June 8 that reducing qualified immunity would be a nonstarter for President Trump.

At the state level, New York lawmakers on June 8 began voting on a package of 10 bills ranging from a ban on chokeholds to the repeal of a statute that blocks police disciplinary records from public view. Democratic Governor Andrew Cuomo has said he will sign the legislation. The Democrat-led Colorado Senate passed a police reform bill 32-1 on June 9.

In many cities, activists are pushing not for reforms—which they say have already been tried and failed—but for slashing police budgets and reallocating the money to social services, schools, and other uses. “Defund the police” has become their slogan.

In Minneapolis, where outrage over Floyd’s death triggered the first protests, most members of the City Council have said they want to dismantle the police department. City Council President Lisa Bender tweeted on June 4 that they would “replace it with a transformative new model of public safety.” Protesters chanted “Shame” and “Go home” at Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey after he said he didn’t support abolishing the police. The 2020 budget for police in Minneapolis is $194 million, which activists had asked to cut by $45 million before the council’s announcement.

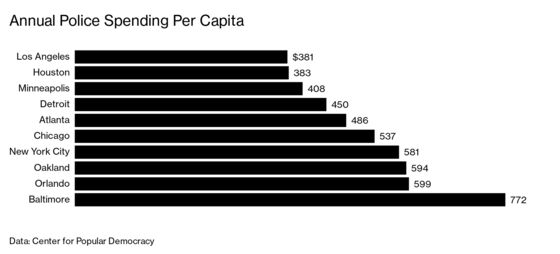

Police budgets have long been sacrosanct. City leaders (and their constituents) want to keep crime low, and police unions wield considerable power. But the protests, coupled with gaping budget shortfalls caused by pandemic shutdowns, are changing the political calculus. In Los Angeles, the police department’s budget was set to increase by 7%, to $1.86 billion, for the fiscal year beginning in July. Instead, Mayor Eric Garcetti said the city would cut it to come up with $250 million in programs for communities of color. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, pressured by activists, said on June 7 that he would divert funding from the city’s massive police force into youth and social services programs.

The cost of policing swelled to $114.5 billion in 2017 from $42.3 billion in 1977, according to an analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data conducted by the Urban Institute. Despite the rising dollar amounts, policing has consistently made up about 3.7% of state and local budgets since the 1970s. However, crime has been trending downward for years.

In Nashville a June 3 City Council meeting on the budget went past 4 a.m. as activists pressed leaders to pull back on police funding. The city-county government, like others, is confronting a fiscal crisis. Mayor John Cooper has sought to address it with a property-tax hike and spending cuts; his budget allocated about $218 million for the metro police for fiscal year 2021, mostly steady from the previous year.

The Nashville People’s Budget Coalition, an advocacy group, has criticized the mayor’s plans, noting in a report that the budget would replace two police helicopters but wouldn’t restore funding cut from affordable housing. Erica Perry, an organizer with the group, says the city is relying on police to respond to issues such as homelessness. “They want to use police to address social issues—which has not worked and won’t work,” she says.

However these policy efforts fare, the protests that spurred them will leave their mark on U.S. politics. Biden’s plan to invest $300 million in community policing will please some reformers but not those seeking more radical changes—including some progressives in his own party. Trump is trying to tie his rival to the “defund” camp regardless. Yet his own law-and-order message is proving less popular than he and his advisers had anticipated.

In 1968, after police beat and tear-gassed antiwar protesters in Chicago, Republican Richard Nixon took advantage of fears over rising crime to win election by a narrow margin, says Steven Barkan, a sociologist at the University of Maine. But today police abuses are being filmed and widely distributed, making them harder to ignore. “We’re really talking about police in a very different way,” Barkan says. “There’s increasing recognition of police misconduct, not just among the public but among city officials and the mainstream Democratic Party.” Whether that will prompt either presidential candidate to rethink his stance on policing before November is unclear. —With Erik Wasson, Romy Varghese, and Polly Mosendz

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.