A Tiny Tyranny in Equatorial Guinea Sustained by Oil Riches

A Tiny Tyranny in Equatorial Guinea Sustained by Oil Riches

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The six-lane highway stretching from Equatorial Guinea’s airport to its multimillion-dollar seaside resort in Sipopo is lined with skyscrapers, a state-of-the-art Israeli-run hospital, and luxury homes surrounded by carefully tended gardens. The 16-mile drive suggests the country’s oil reserves have enriched this tiny 11,000-square-mile West African nation, which has been ruled for almost 40 years by one man, President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo. State media once compared him to God.

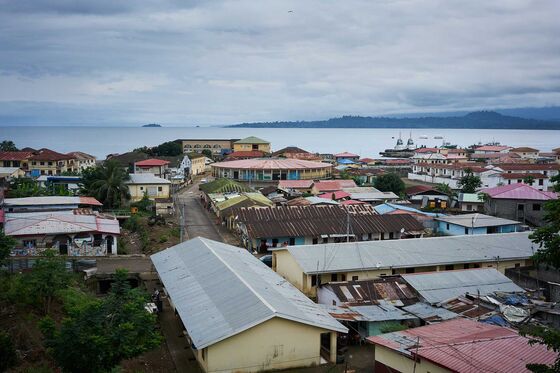

Veer off the route, and the picture that emerges is much less divine. In Fishtown, one of as many as eight shanty communities in the capital, Malabo, hundreds of people live in wooden shacks. Children romp near sewage that flows onto dirt roads strewn with trash. Street vendors sell tomatoes and beans under a mesh of electrical wires that often spark fires. To pass time, unemployed men play Akong, a local board game. Many were idled after Obiang’s building spree ended two years ago. The country has some of the world’s worst social indicators: Less than half of the population of about 1.3 million people has access to clean water, and 20% of children die before reaching the age of 5, United Nations data show. More than half of all children of primary age aren’t in school.

Poverty is in the eyes of the beholder—at least according to Gabriel Mbaga Obiang Lima, one of the president’s sons and the minister of mines and hydrocarbons. He acknowledges difficulties in tackling what he calls “pockets” of destitution, which he blames on the poor having too many children and not saving enough money. “When our peers from Nigeria and Sudan come to see our slums, they say: ‘This is not poverty. Come to our country to see real poverty.’ ”

His father, the president, rules the country from Malabo, which is set on a volcanic island about 150 miles from the rest of the country on the mainland. Obiang’s rise to power began in Spain—the former colonial ruler of Equatorial Guinea—where he received military training at an elite academy during the 36-year-long dictatorship of Francisco Franco. When the African country became independent in 1968, Francisco Macias Nguema was elected president—and Obiang, his nephew, rose to become head of the national guard. Macias hated intellectuals—he even banned the word “intellectual.” A third of the population was killed by Macias’s security forces or fled during his decade-long rule. Obiang overthrew his uncle in 1979. Macias was put on trial and executed by firing squad.

Until the 1990s, Equatorial Guinea’s main source of revenue was cocoa and coffee. Then oil was discovered. (The country is the smallest member of OPEC.) Since then, Obiang has tightened his grip through a system of patronage that enriches his family and allies. Obiang’s eldest son and vice president, Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, flaunts his private jet trips and yacht parties on Instagram. “Teodorin” (or little Teodoro) was convicted in absentia by a French court in 2017 for embezzling more than $100 million of Equatoguinean public money to buy a fleet of supercars and a mansion near the Champs-Élysées. He spent more than $300 million from 2004 through 2011 on luxuries, including Michael Jackson memorabilia, U.S. Department of Justice lawyers said in a separate money laundering case settled in 2014. That sum amounted to slightly less than 10% of Equatorial Guinea’s annual oil revenues at the time and, according to a paper published by the Center for Global Development, would have been more than enough to eradicate the country’s poverty. Teodorin hasn’t commented on either case, but his defense appealed the French court ruling, saying he amassed his fortune legally and has immunity as vice president.

Teodorin is in charge of national security. Under his watch, arbitrary detention, torture, and the killing of dissidents have earned the regime a human-rights record comparable to that of Syria and North Korea in the latest ranking by U.S.-based think tank Freedom House. Teodorin’s half-brother Obiang Lima, the oil minister, dismisses accusations of rights violations and torture as “fake news” spread by international organizations.

Any local dissent, however, is muted. Only 10 public protests were recorded in Equatorial Guinea from 1997 through April of this year, according to Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, a U.S.-based nongovernmental organization that tracks political unrest. Part of the reason for dampened dissent is the conscious underfunding of education by the regime. Activists’ ability to mobilize is limited by the cost of mobile internet access in the country, which is the highest in the world: 1GB of monthly broadband data costs $34.80, well above the $6.96 charged in neighboring Gabon and 73¢ in India, according to data compiled by the Alliance for Affordable Internet.

“Terror and fear has taught our people to swallow their rage,” says Moises Enguru, a pastor and rights activist. “Our generation inherited a useless country. The regime has killed our working culture, education, and morals.” A group of young writers and artists is struggling in secret to nurture a generation of activists who can more effectively challenge the regime. “We need to educate critical minds who can lead the movement,” says one of the organizers who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal. “Change is inevitable, but it may take a while.”

One of the few people to openly criticize the regime is Mariano Ebana Edu, a rapper whose 2013 hit, A Letter to the President, called for equal rights and potable water. On a recent evening, with the music in his jeep blaring, Edu drives through the streets of a slum called Santa Maria. He passes women with buckets on their head lining up to get water from communal taps. Moments later, he’s in the upscale Paraiso neighborhood, where high white walls topped by barbed wire and spanning several blocks seal off Obiang’s private compound. “This is our reality,” says Edu, who goes by the name Negro Bey. “Our wealth is not shared fairly.”

On the sidelines of an oil conference at the Sipopo conference center in April, Obiang Lima says foreign attempts to discredit his father have failed and that the government continues to use oil revenue to improve the lives of Equatoguineans. But poverty has risen since oil prices dropped in 2014, and the country’s production was halved to 120,000 barrels per day from more than 300,000 during peak years, according to the latest World Bank Macro Poverty Outlook.

“Life is getting harder,” says Marcial Abaga, a member of the opposition Convergence for Social Democracy Party, whose home in Fishtown, like many others, has no running water. “If you complain about living conditions, you’re considered an enemy of the state, and you’re ostracized. You become like me.”

Meanwhile, at 77, Teodoro Obiang isn’t loosening his grip on power, despite rumors of ill health and alleged coup attempts. When recent waves of unrest unseated autocrats from Sudan to Zimbabwe, Obiang was unshaken. He’s now the world’s longest-serving president. And he and his family are likely to extend their hold until their oil runs dry.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Howard Chua-Eoan at hchuaeoan@bloomberg.net, Caroline Alexander

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.