A Silicon Valley VC Pioneer Ponders a Smaller-Is-Better Future

A Silicon Valley VC Pioneer Ponders a Smaller-Is-Better Future

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Late last year the exterior of one of the most storied offices on Silicon Valley’s venture capital-studded Sand Hill Road got a makeover. But employees at Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers are having a hard time putting a fresh face forward. Marred by a gender-discrimination lawsuit, bad bets on environmental technology, and perhaps most alarming, dwindling relevance, the firm has been attempting to reinvent itself as it confronts the most severe crisis in its 46-year history.

That challenge became more urgent in mid-September when Kleiner lost high-wattage partner Mary Meeker—aka the Queen of the Internet for her early calls on transformative web trends such as search and e-commerce. She and her team announced they were leaving to raise their own fund and bankroll late-stage tech companies in China and other global hot spots. The split leaves Kleiner and its heir apparent, Mamoon Hamid, to focus on the early-stage bets that made it famous but without the division that was responsible for most of its more recent hits, including Uber, Snap, Spotify, Instacart, and DocuSign.

“This puts them in a tough spot,” says one person who invests across more than a dozen venture funds, not including Kleiner, and requested anonymity to protect sensitive relationships. “Who knows? Maybe being a smaller firm will help them focus.”

It’s not just Kleiner that’s bent on reinvention. Even as Silicon Valley continues churning out hits, traditional VCs find that their place in the industry they created is no longer guaranteed. Competition to bankroll companies is steeper, startups are raising more money and delaying initial public offerings, and the rise of #MeToo has led to a shift in office culture the VC world has been slow to embrace.

By most accounts, Meeker’s split from Kleiner was amicable. Sources close to the firm say her growth investing strategy—which handed $30 million to $100 million checks to mature companies and looked for returns of three to five times within three to five years—was simply too different from that of the firm’s venture group. Investing more on potential, rather than predictable performance, the venture group wrote a larger number of checks for smaller amounts. Its sweet spot was $2 million to $10 million, aiming for a return of 5 to 10 times within a decade. Geography was also an issue. Meeker’s team increasingly pursued deals outside the U.S. and had explored opening an office in China. In contrast, Kleiner’s venture group raised a $218 million China fund in 2011 but has backed few companies outside the U.S. in recent years.

The gap between the groups often caused confusion and sometimes led to missed opportunities. For example, the firm passed on the chance to get into personal-finance startup Robinhood Markets Inc. at a $1 billion valuation, then later invested at $5 billion, according to a person with knowledge of the deal.

“If you don’t have the synergy, why force it? It ends up suboptimizing what each of us do,” says Ted Schlein, a general partner at Kleiner for more than two decades who helped recruit Meeker and launch the growth strategy. “The venture landscape has changed.” Meeker declined to comment.

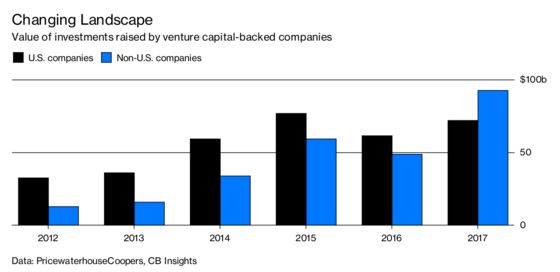

Venture capital has evolved since the financial crisis. New rules governing public companies have made IPOs less appealing to startups, and the pool of potential investors has grown, making it easier for private companies to fund themselves without going public. The venture industry doled out $164 billion worldwide last year, a level not seen since the go-go days of the late-1990s, according to industry research group CB Insights. That increase has been driven by nontraditional venture investors, including sovereign wealth funds such as Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund. The Saudi fund also backs SoftBank Group Corp.’s hulking $100 billion Vision Fund, the industry’s largest. And corporate investors have returned to the market at levels of the dot-com heyday.

At the same time, very-early-stage startups, with the help of cheap web hosting from Amazon.com Inc., and developer resources like GitHub Inc. are able to build companies more quickly and cheaply than their predecessors. They build, test, and launch—and acquire users—faster than ever before. Early venture investors writing smaller checks are being pushed to develop deep knowledge of niche businesses while also investing globally, since the next hot company can emerge from anywhere.

Unlike during the dot-com boom, which was concentrated in the U.S., roughly half the startup deals completed in 2017 were done outside the U.S., with Asia-based companies attracting nearly half the total cash, according to CB Insights.

Not every longstanding firm has struggled. Sequoia Capital, founded the same year as Kleiner, has funds dedicated to China and India, venture, and growth. But while Sequoia has gotten larger, finalizing a massive $8 billion investment vehicle this spring, Kleiner has retrenched.

After missing most of the social media revolution and a disastrous attempt to invest in green tech, Kleiner began paring back its ambitions. It launched a fund to support companies developing iPhone apps, another to bankroll social media startups, and an initiative to back Google Glass developers. All three have ceased operations. Kleiner also shuttered a seed investment program for very-early-stage businesses last year when three staffers leading it left to become startup founders.

A slimmer Kleiner is returning to the riskier—but potentially more lucrative—style of VC investing that led to its reputation-making stakes in Genentech, Netscape, Amazon, and Google while they were in their infancies. “The new Kleiner is the old Kleiner in a way,” says Schlein, who is now mentoring Hamid, 40, to take the firm’s managing reins from legendary tech VC and Kleiner Chairman John Doerr.

In many ways, Hamid represents the new face Kleiner would like to put forward. Born in Pakistan, raised in Frankfurt, and educated at Stanford and Harvard, Hamid was an early investor in breakout successes including Box Inc. and Slack Technologies Inc. Since he joined Kleiner last year, Hamid has been coaching existing companies and recruiting partners to join the team. He said one or two women investors could join in the next few months. The partner roster at Kleiner, like those at three-quarters of all U.S. venture firms, is now all male.

So far this year, the firm has made more than two dozen new venture investments. Most are early- and mid-stage bets mainly on U.S.-based startups, though several have engineering teams in Israel and elsewhere. It may take as long as a decade to determine the success of those bets.

Endowments, pension funds, and others that invest in venture funds use multiyear track records when deciding whether to reinvest. Kleiner’s 14th and 15th funds still rank in the top 25 percent of all venture funds of the same year; its next two funds, raised more recently, are too young to show results. Still, when it begins raising its 18th fund next year, Kleiner is likely to trumpet a smaller-is-better strategy as the best way forward. For now at least, it doesn’t have much choice.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Dimitra Kessenides at dkessenides1@bloomberg.net, James Ellis

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.