A Sense of Climate Urgency Takes Hold in Davos

The World Economic Forum can make a difference if influential participants go home with a determination to do better.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Davos is cloaked in white, but its agenda is green. Environmentalism—fighting climate change in particular—has emerged as one of the biggest priorities of the World Economic Forum annual meeting, which is held every January in the Swiss ski village.

It’s easy to poke fun at Davos. In years past, about 1,500 private jet flights have delivered some of the world’s wealthiest and most powerful people to the event, where they pay $70,000 a ticket to talk about how the world should shrink its carbon footprint. There’s a risk that the forum’s spotlight on climate change could backfire by strengthening the impression that keeping the planet from overheating is something that only the elites hanging out at the Davos Congress Centre and the Steigenberger Grandhotel Belvedere care about.

But don’t underrate the power of talk, something at which Davos Woman and Davos Man excel. The biggest obstacle to fixing the planet’s climate is free-riding—shirking efforts to fight climate change while benefiting from the efforts others make. The repeated interaction with fellow delegates in climate sessions at Davos can fight the free-rider problem by creating a sense of urgency around the need for collective action on climate change. The unofficial motto of Switzerland, after all, is unus pro omnibus, omnes pro uno: One for all, all for one.

Galvanizing the determination of Davos delegates to do better when they get back home can have lasting consequences because the attendees are influential: prime ministers and presidents, chief executive officers from around the world, heads of nongovernmental organizations, big-name journalists, and a dollop of artists and performers.

The first-listed of six priorities for this year’s conference is “Ecology: How to mobilize business to respond to the risks of climate change and ensure that measures to protect biodiversity reach forest floors and ocean beds.” There are sessions with titles such as The Big Picture on Climate Risk, Solving the Green Growth Equation, Calling for Climate Justice, and Responsible Tourism in the Age of Climate Change. Even some of the featured artists are green: Futuristic artist Daan Roosegaarde of the Netherlands is presenting at a session called Can We Live in True Harmony With Our Environment?

About 18% of the sessions at Davos this year are devoted to climate change, along with other environmental topics and sustainability, vs. about 13% in 2010, when recovery from the financial crisis was more top of mind. The forum will publish a universal ESG (environmental/social/governance) scorecard devised by its International Business Council, which is chaired by Bank of America Chief Executive Officer Brian Moynihan. “Climate change has shot up the agenda over the last year,” says Adair Turner, a Davos regular who was chairman of the U.K.’s since-disbanded Financial Services Authority.

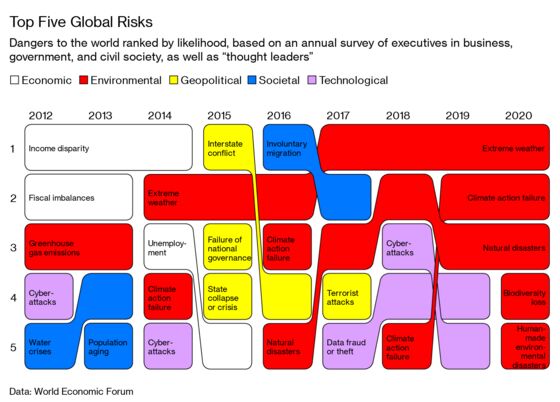

On Jan. 14, occasional Davos attendee Larry Fink, the CEO of BlackRock Inc., the world’s largest asset manager, issued a letter to CEOs saying that “climate change has become a defining factor in companies’ long-term prospects.” The next day the World Economic Forum released its annual Global Risks Report, in which climate change and related environmental issues, for the first time, swept all five of the top spots, ranked by likelihood.

Why now? One reason is that the issue has become more urgent. Despite progress on electric cars and renewable energy, the planet continues to grow hotter. In December the World Meteorologic Organization said Earth could heat up by 3C to 5C (5.4F to 9F) from its preindustrial level by the end of the century. That would be triple the 1.5 C that scientists say is the most the biosphere can handle without serious problems, such as inundation of coastal cities and desertification of rainforests.

Another reason is that the organizers of the World Economic Forum seem to have concluded that bringing an end to climate change free-riding is going to require business, government, and civil society to work together. It’s been 2½ years since President Trump pulled the U.S. out of the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change mitigation. The withdrawal made clear that business as usual in climate diplomacy wasn’t cutting it, says Nathan Sheets, chief economist of PGIM Fixed Income, who worked on climate issues as the U.S. Treasury Dept.’s under secretary for international affairs in the Obama administration.

That’s where the Davos talking cure comes in. “Davos Man doesn’t do humility well, but on climate change there’s a feeling that there needs to be a more symbiotic relation between business and policymakers,” says the U.K.’s Turner.

It’s not easy for Davos attendees to dodge accusations of hypocrisy. Most are prosperous by any standard, and wealth is strongly correlated with the production of greenhouse gases. According to Oxfam, the richest tenth of the world produces 60 times as much in greenhouse gases as the poorest tenth. “How are the elites represented at Davos going to persuade ordinary people to make sacrifices in the struggle to limit climate change?” Anatol Lieven, a Georgetown University Qatar professor and the author of Climate Change and the Nation State, wrote in an email.

Sensitive to that question, the Davos organizers are trying to make the conference itself as green as possible (for a retreat in the Alps in January). They’re discouraging private jets and single-use plastic containers while installing solar panels and geothermal heating. Organizers say the forum has been offsetting 100% of emissions, including air travel, since 2017. Last year the offset program funded efficient cook stoves in China, India, Mali, and South Africa and biogas installations on Swiss farms, among other projects. On “Future Food Wednesday,” the menu will be “rich in protein but meat- and fish-free.”

Despite such mostly symbolic efforts, the burden of fighting climate change is likely to fall disproportionately on the poor and working classes, says a study by Deutsche Bank that’s to be presented in Davos. For one thing, these classes spend a bigger share of their income on fuel, so they’re harder hit when fuel taxes go up to discourage usage, notes the report, which is by Jim Reid, Deutsche Bank’s global head of thematic research, and others. France’s Yellow Vest protests forced President Emmanuel Macron to abandon a fuel tax hike in 2018.

On the other hand, tapping the brakes on reform isn’t a practical option for Davosians, either. While the poor bear inordinate costs of fighting climate change, they also suffer the most from its consequences—floods, fires, crop failures, and the like. This year the forum is inviting back Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg, now 17, who told attendees last year, “I don’t want your hope. I don’t want you to be hopeful. I want you to panic … and act as if the house was on fire.”

This year, Thunberg and a small army of activists and school strikers are coming to Davos from around the world to demand complete and immediate divestment from fossil fuels. “We don’t want these things done by 2050, 2030 or even 2021, we want this done now—as in right now,” 21 of them wrote in an open letter published in Britain’s Guardian on Jan. 10.

In short, what’s too much for some is too little for others. Davos is all about forging consensus through conversation. But on climate change, the leaders can’t be sure that anyone will follow. —With Thomas Buckley and Simon Kennedy

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Eric Gelman at egelman3@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.