A Gas Heist Gone Wrong, an Explosion, and 137 Deaths in Mexico

A Gas Heist Gone Wrong, an Explosion, and 137 Deaths in Mexico

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The morning before 137 people died in Mexico’s deadliest pipeline explosion, clouds gathered on the horizon above Tlahuelilpan, a town two hours north of Mexico City. As the rising sun flicked the mountains poking out of the flatlands on Jan. 18, locals who worked in the nearby fields or factories left home to earn their daily wage.

The day passed like any other. Around 2:30 p.m., 25 soldiers on patrol spotted a horde of people jostling and yelling at Mile 140 of the Tuxpan-Tula pipeline. They were engaged in another of the area’s major occupations: siphoning gasoline.

That wasn’t surprising in and of itself. The patrol was there to protect the pipeline, which carries fuel from Mexico’s east coast to the major refinery in Tula, near Tlahuelilpan, on behalf of Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), the state-owned oil company that accounts for about a fifth of the country’s $174 billion in annual tax revenue. Tlahuelilpan’s home state of Hidalgo is infamous for huachicoleo, the illegal tapping of fuel from pipes that lie several feet underground. Over the past decade, the practice has spread across Mexico, but Hidalgo is one of the most affected areas. “We have the largest number of pipelines in the country,” says Ricardo Baptista, a local congressman. “Huachicoleo has been going on here for more than 25 years.” According to Pemex, Tuxpan-Tula had been breached 10 times in the preceding three months, and pipelines in Hidalgo were tapped more than 1,700 times in 2018.

A typical huachicoleo involves two or three people soldering and tapping the pipe and a group of halcones, or hawks, keeping watch. The solderer and his teammates use high-power drills to perforate the pipes, then affix taps and sometimes a hose to retrieve as much fuel as their portable tank can carry, generally into the hundreds or thousands of gallons. “This requires lots of balls and know-how,” says one huachicolero, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal. He’s used to throwing water on the pipes to keep them cool. “If you don’t know how to make the hole or solder properly, and you make one stray spark—my God.” Meaning: kaboom.

Generally, these extractions, or tomas clandestinas, are coordinated operations run by gangs in the dead of night. Out in the midafternoon sun, the soldiers immediately realized the thieves they’d spotted weren’t professionals. The scene in the green alfalfa field abutting the pipeline appeared to be a free-for-all, roughly 80 villagers swarming a leak inside a 100-foot-long, 5-foot-deep irrigation trench that bisected the field. There seemed to be no organization, no tap, no hose—only two holes in the pipe, which made the fuel spurt as if from a wonky fountain. It seemed possible a local huachicol gang had screwed up the extraction, but the holes had none of the typical hallmarks. The villagers didn’t seem to care. They were dancing and frolicking amid the shimmering torrents of fuel, scooping up what they could in red jerrycans.

Following protocol, the soldiers notified Pemex and set about trying to control the crowd and close off the area. But the latter goals proved impossible as the number of villagers swelled from 80 to at least seven times that over the next few hours. Vastly outnumbered, the soldiers looked on as men, women, and children arrived in trucks and cars, carrying jugs, bottles, buckets, or whatever else they could find. The villagers on the scene had spread the word online, in videos, tweets, and WhatsApp messages. “They’re giving away gasoline,” read a typical message. “It’s free. Come and get it.”

Huachicoleo is becoming one of Mexico’s most pressing economic issues. In 2018 thieves made off with about $3 billion in gas from 12,500 siphonings, almost double the number of thefts of two years earlier. The motive comes down to math. “Most people here earn around 1,500 pesos [$78] a week in a normal job, but by doing this you can get your hands on 2,000 pesos a night for being a hawk and up to 15,000 pesos for being the one who solders the tap,” the Hidalgo huachicolero says. “In an area where people were not long ago riding donkeys, they now have fancy cars.” He and other gang members say a night’s worth of stolen fuel, sold on the black market, can net their bosses roughly $46,000 in profit.

Interviews with nearby residents, first responders, Pemex security staffers, politicians, and huachicoleros themselves suggest the trade has grown scarier, too. Whereas in the 1990s the huachicolero sometimes cut the figure of a dashing lone vigilante, sharing the stolen oil wealth among friends and neighbors like a hero of folklore, today the business is far more structured—and bloody. Drug cartels are steadily killing or scaring off the homegrown gangs to take the huachicoleo revenue for themselves, using domestic sales to supplement their international narcotics trafficking and engendering the type of violence more commonly associated with the drug trade. In January, the day after the Tuxpan-Tula was perforated, a huachicol gang leader nicknamed El Parka was shot dead, and three more crime bosses have been assassinated since. A study conducted by Etellekt Consulting estimates that cartels are now responsible for 95% of illegal fuel extractions.

The crowd at the Tuxpan-Tula pipeline on Jan. 18 didn’t look like a bunch of gangsters. Many of the survivors say they’re among the 43% of Mexicans living below the poverty line—about $1,940 a year in the city, $1,260 in the country—and can’t afford to ignore free money. Several complained that President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s spate of pipeline shut-offs at the beginning of January has exacerbated their problems. The government has said the temporary closure of these pipelines, and the deployment of 5,000 soldiers to monitor Pemex facilities, reduced fuel theft from a daily average of 80,000 barrels to only 2,500. Locals say that with area gas stations drained of fuel or packed with customers, they had a tough time getting to work.

The pipeline spill, however, represented opportunity. “I’m sure that the majority of people went down to the field because their friends and neighbors had posted it on Facebook,” says Baptista, the congressman.

Juan Serrano, a lanky 17-year-old with a mischievous grin, was among the curious. Serrano lived in a small house jumbled with birdcages and car parts in the colorful neighborhood of San Primitivo, less than a mile from the pipeline. His mother, Regina, told him he wasn’t allowed to go down to the field, but as his friends and a stream of passersby headed that way, he hopped the back wall of his yard without his parents noticing and made for the pipeline.

When he arrived at the spill site around 5 p.m., about 600 people were crowding the trench, and the field was dotted with containers. “There were so many people,” he says—people with bloodshot, teary eyes from the gas and T-shirts over their nose in a vain effort to filter the fumes. Others were pitching and swaying, gurgling and slurring, smoking and dancing. More than two hours after the soldiers reported the incident, Pemex still hadn’t shut off the fuel supply, and the two jets of fuel were shooting 20 feet into the air, forming two coruscating arches.

Alfonso Durazo, Mexico’s minister for public security, later said the pressure inside the pipe was too high for the shut-off fuel valves to close fully. But it’s tough to take that at face value. The government freely admits that Pemex workers are usually the ones who tip off the huachicoleros. Last year an official government estimate put the share of pipeline thefts committed with Pemex support at 80%. “These are the guys that tell you which pipeline has fuel in it and at what time,” Baptista says. Bloomberg Businessweek contacted Pemex for comment; a spokesperson for the company didn’t provide one by publication time.

Bathed in the gas fumes, Serrano, like many of the other amateur huachicoleros, couldn’t tell anyone much of anything. He was experiencing several of the symptoms typical of intense gas exposure: lightheadedness, blurred vision, slurred speech, and a touch of euphoria. “There were points when I couldn’t stand, it was so strong,” he says. “People were fighting, others laughing, and most were drunk on the fumes. They were throwing gas at each other.” After he’d been there a little more than an hour, he suggested to his friends that they leave. They didn’t.

The army had shut off the main road by 6:30 p.m., and two more platoons had arrived, along with local and national police. Although the authorities declined to disclose just how many troops ended up at the pipeline, López Obrador would later insist they remained outnumbered by the villagers. The soldiers stayed on the perimeter, fearful of causing a riot, letting vehicles full of new people pass as they arrived.

One of the newcomers was Rene Ceron, a portly 40-year-old farmer with the eyes of a bloodhound. He’d heard about the robbery several hours earlier while working in one of his cornfields a few miles away. “A friend of mine sent me a message. He told me they were giving away fuel in a nearby field and that I should come,” he says. When Ceron reached the trench, it was brimming with thick pools of gasoline and hundreds of human bodies trying to pilfer it. Above him, the two jets geysering from the ground left gas falling onto his face like fine, cool rain. The air reeked of rotten eggs.

It was also beginning to get dark and to cool down, and the extremely flammable vapor released by the high-octane gas was no longer rising with the afternoon heat. As the temperature fell, the fumes began to settle down closer to the crowd. Those already inebriated on them continued scooping up buckets of gas. For Ceron, who’d been there only a few minutes, something changed. “I suddenly felt death in the air,” he recalls.

The authorities say it was static electricity that lit the spark at about 6:50 p.m. A handshake, perhaps, or the rub of a shoulder through a polyester T-shirt, or an errant grip on a plastic jerrycan. All Ceron heard was a low hiss, then a whoosh that sounded like paper ripping, as a bright yellow flame swept from near the main road and into the trench, then soared more than 60 feet into the air. Ceron turned his back and felt the intense heat, then a pain that he says he’ll never be able to properly communicate. He passed out.

When he came to, all he could hear was screaming, car horns, and the roar of the fire. People were rolling on the ground, or crying for water, or simply running from the scene, still aflame. The air smelled of burnt hair and flesh. As Ceron hauled himself up, his head felt heavy, his ears buzzed, and his back felt like hot oil. “Throw yourself on the ground!” people were shouting. He had no idea where he was.

Ten minutes after the explosion, firefighters and paramedics in Tlahuelilpan received the calls they’d been dreading as they followed the pipeline spill on social media like everyone else. Huachicoleo-related fires aren’t unheard of—the fire unit had put out one a week earlier—but the first responders weren’t prepared for this one. A mob of people ran at their vehicles screaming and pleading for help, their clothes and skin ragged and smoldering.

Adan Lugo, a 27-year-old former firefighter who’d been hanging with his old buddies at the station, drove the fire engine as close to the field as he could, until the flames were belching and spitting from the trench about 200 feet in front of him. The figures on the ground were so charred, he struggled to tell the living from the dead. He worked for an hour with paramedics, soldiers, and able-bodied bystanders to drag survivors from the field to waiting medical personnel. Sometimes, the best that rescue workers could offer was nothing. “I remember seeing one man curled up in pain. His body was slathered in mud and grass to soothe his burns,” Lugo says. “I was worried he would get an infection, but the people watching over him told me that I should let him be.”

Three hundred feet away, Serrano watched the flames and heard the screams. Four minutes earlier, he’d finally decided to go home after he’d tried and failed to persuade his friends to join him. Those four minutes saved his life but left him to witness their death.

As ambulances began ferrying the injured to hospitals across Hidalgo and farther afield, Pemex’s own firefighters also arrived, but their fire engines and hoses malfunctioned, so Lugo’s team ventured deeper into the scorched field to look for more survivors. Filling the void of the screams was the deep plane-engine hum of the fuel as what was left in the pipes spurted out and caught fire. As Lugo and one of his comrades approached the blaze, the heat stinging their skin through their protective suits, it became clear they wouldn’t find more survivors closer to the source. Everyone left in the field was dead, and most of them were on fire.

At a certain point, Lugo says, the sheer horror of the experience crossed a line into a kind of tragic absurdity. He and the other firefighter were using extinguishers to douse the bodies, but most were so soaked with gas that they quickly reignited. “I would be extinguishing the 10th body, and the first one was already on fire again,” Lugo says. “It was the worst scene I’ve ever attended.”

By midnight, many of the 71-and-counting injured were at or en route to hospitals 10 miles or farther away, and the government ordered four helicopters to evacuate the most grievous cases to Mexico City. Yesenia Mendoza, a 23-year-old nurse trainee, knew by then that her 17-year-old brother was alive, being treated for severe burns over most of his body, and that her dad, still among the missing, was probably dead.

The fire had at last been extinguished around 11:45 p.m., thanks to only three Tlahuelilpan firefighters with working equipment. Where there had once been a spitting, hissing blaze, there were now swamps of foam and water and hundreds of locals searching in the ashes for their relatives. At about 3 a.m., Mendoza and her sister went to the scene to search for their father and pleaded their way past the cordon of soldiers who were by then encircling the alfalfa field. Alongside half-melted buckets, containers, and bottles, they saw burned clothes, charred bones, and the skin of a hand lying in the dirt with all its fingernails intact. Each new body they approached triggered the fear that it might be their dad. But after 20 minutes the police asked them to leave. There was no sign of him.

The fateful clue appeared the following evening, while the sisters were closing up the family convenience store. A cousin who’d been out looking in the fields texted a photo of their father’s cherished pendant in the shape of a horse, found close to a person’s remains. “When my sister showed me the photo, I went into shock,” Mendoza says. “ ‘Why my dad?’ I said. I could not accept it.” Eventually she managed to call her mom, who was watching her brother in the hospital. “I have to tell you something,” she began. “You need to be strong.”

In the months since the fire, relatives of the dead and disappeared have built a shrine near the explosion site. In the center of the field, a mass of wood and marble crosses have encroached on a crooked, scorched tree. There, relatives still come daily to lay flowers and sit on blue plastic chairs or flimsy wooden crates, sobbing into handkerchiefs or staring at the ground. The deep trench that once bisected the green field has been filled in permanently with coarse yellow sand.

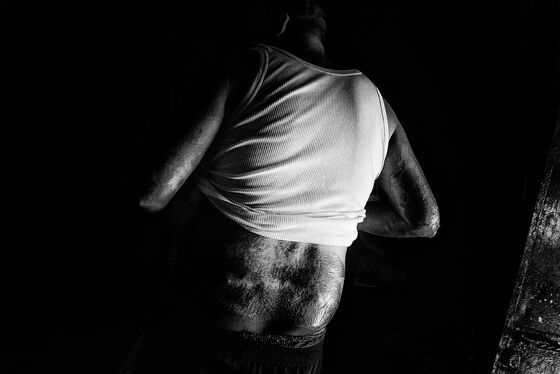

Serrano, the teenager, is suffering from traumatic stress, having watched his friends and neighbors die as he stood a few hundred feet from the epicenter of the explosion. Ceron, the farmer who was closer, is still recovering from second-and third-degree burns covering 60% of his body. The blisters on his face swelled like mushrooms, and the skin on his hands was burned to the bone. In the hospital he suffered from feverish nightmares of wildfires consuming his recovery bed. He hopes to return to work soon. For now he wears white cotton clothes over his burned hands and walks with discomfort. Lugo has continued to hang out at the fire station with his former colleagues, but he can’t shake his memories of the scorched bodies, the smell of the singed hair, the feel of the heat. Mendoza buried her dad on his 51st birthday, and her mother accompanied her brother to an indefinite stay at Shriners Hospital for Children in Galveston, Texas.

The people of Tlahuelilpan are in mourning, says a local priest, but they don’t know how to move forward. Many survivors remain willing to believe the fire was a tragic accident, but others blame the government for letting the huachicoleo business get out of hand or for letting the region otherwise stagnate. If there were better jobs, locals say, people in Hidalgo wouldn’t have to resort to huachicoleo.

In May, López Obrador said his government had reduced fuel robbery in Hidalgo by half, and across Mexico by 95%, since he declared war on the thieves last year. But Pemex’s losses to huachicoleo in the first four months of 2019 amounted to more than $2.6 billion, almost sixfold more than the total stolen during the first third of 2018. In that time, Hidalgo reported 1,885 thefts, an annual increase of 211%.

Notwithstanding the evidence of systemic corruption, Pemex and other government officials say they’re committed to justice. The Mendoza sisters, however, say seeking out a guilty party is a low priority for them, at least for now. They’re trying to survive the consequences of the fire and get used to the idea of being alone in Hidalgo. —With Amy Stillman

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeff Muskus at jmuskus@bloomberg.net, Jillian GoodmanMax Chafkin

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.