A Live Reality Cop Show Is Cable TV’s Best Bet to Compete With Streaming

A Live Reality Cop Show Is Cable TV’s Best Bet to Compete With Streaming

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On a Saturday night in July in Salinas, Calif., officer Cameron Mitchell began pursuing a suspected stolen car. As a couple million TV viewers watched at home, Mitchell chased the vehicle over curbs and through crowded intersections. He attempted what’s known as a PIT maneuver, nosing his car into the side of the fleeing vehicle to get the driver to spin to a stop. But Mitchell instead lost control and his squad car skidded frighteningly to a halt on a median. In the end, the officer was fine and the suspect gave himself up a few blocks later after other Salinas police vehicles surrounded him.

It’s all in a typical night on Live PD, the hit show that’s helped lift the fortunes of A&E Networks Group and is showing at least one way TV companies can survive competition from streaming services like Netflix. Continually switching between cameras recording the real-time exploits of officers in eight locations around the U.S., Live PD combines a classic TV staple—the police show—with live elements that many viewers find irresistible.

“Crime is hot,” says Scott Robson, an analyst who follows television for S&P Global Market Intelligence, citing everything from crime-focused networks, such as Investigation Discovery, to the surge in serialized crime podcasts. Live PD added a new twist: unpredictability. “With the live format,” Robson says, “you never know what’s going to happen next.”

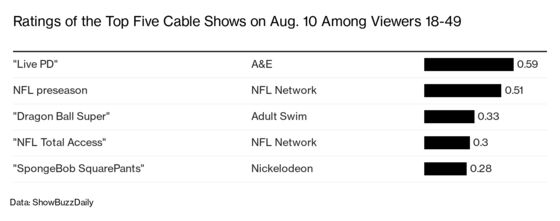

The show, now in its third season, is often the No. 1 program on American cable TV on Friday and Saturday nights. A&E is one of only two cable channels to show growth in 18-to-49-year-old viewers since September 2018, along with TLC.

A&E, jointly owned by Walt Disney Co. and Hearst Corp., runs six hours of new Live PD episodes a week. There are hours more of reruns and seven spinoffs, including Live PD Presents: Women on Patrol and Live Rescue, which focuses on firefighters and other first responders. Top Dog, which features police dogs competing on an obstacle course, is set to make its debut in the fall.

In a way Live PD is a return to the network’s heyday six years ago when it thrived on red-state reality shows such as Duck Dynasty and Dog the Bounty Hunter. Programming at A&E—which had started out showcasing fine arts such as opera and classical dance in the 1980s—drifted after those reality hits ended, and the channel even toyed with scripted dramas. In 2017, less than a year after Live PD’s debut, A&E canceled all its scripted shows and went all-in on reality. Says A&E President Paul Buccieri: “We think we’ve struck a real opportunity with live unscripted storytelling.”

Live PD has flown largely under the radar of national media. That’s partly because police departments in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago haven’t been interested in participating. “I think that more people in other parts of the country are probably touched by law enforcement,” says the show’s host, longtime network TV legal commentator Dan Abrams. “They have friends, relatives that are in some ways connected to it.”

Live PD is the creation of Big Fish Entertainment, a production company acquired last year by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Inc. Prior to Live PD, Big Fish was best known for shows such as VH-1’s tattoo parlor reality show Black Ink Crew. Company founder Dan Cesareo says his team got the idea for Live PD after reading an article about how police were streaming arrests on Twitter. The nation had been roiled by protests over police killings of unarmed suspects such as Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo. Cesareo pitched the program to police chiefs as a way for the general public to see the whole story, not just clips that end up on the evening news. He’s still surprised so many said yes. “We were asking them to sign up for what could be their worst nightmare,” Cesareo says. “Let’s broadcast your worst day at work live on television.”

A typical Live PD episode follows two officers each in eight cities or counties. A camera person rides in the cars, which are also equipped with cameras. Abrams hosts the show from A&E’s Manhattan headquarters, switching between live feeds to highlight whichever story seems most compelling. (An occasional segment is identified as having taken place “earlier,” which could mean hours or days.) Current and former police officers provide in-house analysis, while Abrams offers a steady stream of deadpan quips. “She wanted the UberX version of that car,” Abrams said one Friday night in August after a woman stopped for walking in the middle of a busy road in East Providence declined a ride in the back of a squad car. The officers put her in an ambulance instead.

Live PD offers a mix of the mundane and the terrifying. In the first season, viewers watched a fleeing suspect flip his car and try to run holding his two-year-old daughter as a human shield. As the camera rolled and a crowd gathered with cellphones out, Richland County, S.C., sheriff’s deputy Chris Mastrianni wrestled the man for more than two minutes until backup arrived. At one point, the suspect reached into his pocket for what might have been a weapon.

Richland County Sheriff Leon Lott was among the first to sign on to the show and he says he has no regrets. The department gets fan mail and job inquiries from across the country, he says. Some 5,000 fans came to Columbia, the county’s largest city, for a celebration of the 200th episode in April. “I think Live PD is the future of law enforcement,” says Lott. “Five to 10 years from now, everything that law enforcement does is going to be livestreamed somewhere. I saw this as an opportunity to get on the front end of something everybody’s going to be doing.”

Some departments, including Bridgeport, Conn.’s, have stopped working with the show. And last year, the Spokane City Council passed an ordinance making it difficult for police shows to film there after some residents objected to how the city was portrayed.

Dan Taberski, host of the Running from Cops podcast, which dissects the long-running syndicated show Cops, devoted a couple of episodes to Live PD earlier this year. Taberski’s team interviewed residents of Spokane and Tulsa who appeared on the show. They complained that police targeted them for minor infractions because they knew they’d make for good television and that the show never asked permission to feature them. “A show that presents itself as being transparent asks no hard questions of police,” Taberski says.

Live PD producers say that if some of those being filmed object, their faces are blurred out. But mostly Cesareo says the show doesn’t need to get the subjects to sign releases to include them because the events are playing out in public, live.

That immediacy keeps viewers engaged, as during an incident in June in Williamson County, Texas, where a man pulled over for a missing license plate and suspected of being intoxicated tried to run after officers asked him to get out of the car. It took four deputies, using their fists, a chokehold, and a taser to subdue him. Half the people watching probably thought the officers used too much force; half probably felt that it was justified, Cesareo says. “That’s the perfect moment for the show,” he says. “You want those discussions.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Ellis at jellis27@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.