Buying 87,000 Acres of Land Was Easy. Giving It Away Was a Lot Harder

Buying 87,000 Acres of Land Was Easy. Giving It Away Was a Lot Harder

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- It’s like that philosophical question about whether a tree falling in the forest makes a noise if no one’s there to hear it. In this case, does an 87,500-acre recreational area in Maine’s North Woods exist if there are no road signs to help visitors find it?

“The governor wouldn’t let the signs go up on the interstate, so unless you knew it was there, you didn’t know it was there,” says Roxanne Quimby, the 69-year-old co-founder of Burt’s Bees and donor of those acres to the federal government. “And if you knew it was there, you didn’t know how to get to it.”

Now, more than three years since the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument was established and about a year since that two-term Republican governor moved on, signs are finally going up. It’s a major milestone in the saga of an ambitious philanthropic vision to unite and protect lands for the public that was met by howls of protest from the local community.

Quimby took the first steps about 20 years ago to create what she hoped would be a national park. With her natural toiletries company throwing off a lot of cash, she bought land at $200 an acre as International Paper Co. and other forestry product companies, the area’s longtime employers, sold off timberland. Later, she got a lot more money to deploy: In 2003, 80% of her brand was sold to a private equity firm for $147 million, and an additional $150 million arrived when Clorox Co. bought Burt’s Bees in 2007.

In 2011, Quimby unveiled her plan. Then-Governor Paul LePage vehemently opposed it, claiming it would further hurt the logging industry and bring unwanted federal regulation. “This over-cut forest land was not worthy of any designation,” he said in congressional testimony in 2017. “It was simply the product of Washington politics.” For a long time, local sentiment was—to put it mildly—negative. Quimby didn’t want Maine pastimes such as hunting and snowmobiling on the land, which didn’t endear her to locals. They weren’t keen on the terrain—to many, symbolizing their livelihoods—moving into the hands of the federal government, anyway.

“People needed someone to blame for the loss of their lifestyle and weren’t blaming International Paper,” Quimby says. “They focused a lot of anger, grief, frustration on me, because I was easy to identify—some lady that makes lip balm, and what the heck is she doing up here telling us we can’t go hunting on our land?”

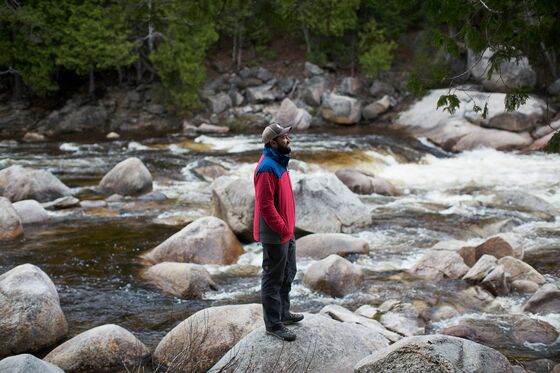

A battle-scarred Quimby asked her more diplomatic son, Lucas St. Clair, a then-33-year-old Mainer and outdoorsman, to take over the quest in 2011. St. Clair went on a charm offensive, emphasizing the rebuilding of the region’s economy through tourism. “I spent thousands of hours having coffee with as many people in the community as I could,” he says. “I just kept showing up for years, and eventually all the questions got answered, and people started focusing on the economic benefits.”

And so, in August 2016, St. Clair and his mother shared both victory and minor defeat. President Barack Obama designated the land a national monument, complete with a $20 million endowment from Quimby. She’d compromised to allow hunting and snowmobiling in parts of the monument to gain local support, but she didn’t get the national park designation. While national monuments are created by presidential proclamation, national parks must go through Congress. Their functional differences are minor.

Quimby, who’s spent about $70 million buying land, recently ran into opposition to another plan for the park. She retained rights to build the monument’s infrastructure for seven years and hired prominent architect Todd Saunders to design a welcome center that would be an attraction in itself and guide visitors to uses for the land, such as hiking, cross-country skiing, camping, and canoeing. St. Clair estimates it could cost as much as $12 million. Quimby’s personal foundation made a pledge to match $5 million in outside donations.

Quimby was ready to move on the project when St. Clair had representatives from local American Indian tribes look at the design. They had an immediate aversion to its echo of early Maine farmhouses. “They felt it represented the tyranny of the white colonization of Maine,” says Quimby. “They’d never lived in anything that had a right angle.” Saunders redid the design, which is now curvy, and “people say it looks like a mushroom that has grown out of the landscape,” explains Quimby. It must be built by 2023 or builders will lose the right to construct on the land.

Quimby has visited 40 of the nation’s 61 national parks. She visited 24over six years as a board member for the National Park Foundation, which meets quarterly in different parks.

Obama created or expanded 34 national monuments.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Chris Rovzar at crovzar@bloomberg.net, Justin Ocean

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.