American Way of School Funding Is ‘Uniquely Bad’ for Inequality

American Way of School Funding Is ‘Uniquely Bad’ for Inequality

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The primary school in Crellin, Md., a village of 260 people, sits on a reclaimed coal-loading site in the Appalachian Mountains. On top of reading, writing, and arithmetic, students get to look after chickens and lambs in the barn outside. They also learn about pollution by testing water from the nearby river.

It’s a place full of warmth and curiosity—and, like most of the families who send their children there, it’s short of money. “I want them to have choices,” says principal Dana McCauley of the kids in her charge. The school has earned widespread recognition for its environmental education program. But there’s no money for tutors, and funds for the school’s math academy have dried up.

Rising inequality is now at the heart of U.S. public debate, looming over just about every policy discussion from trade to interest rates and likely to take center stage in this year’s presidential election. America’s classrooms are one place where the trend could be halted.

McCauley and her staff are battling to give children from low-income families a better educational start. That can lead to decent paychecks and a stake in an economy that’s become more oriented toward skills and knowledge. But because of the way the U.S. school system is funded, it often perpetuates inequality instead. The reality is that McCauley’s school would have more resources if the children who went there were better off.

Maryland—one of the more prosperous states but also one with pockets of hardship in places including Baltimore and rural areas like Crellin— is trying to disrupt this loop in which underfunded school systems produce poor adults. It’s embarked on what some experts say is one of the biggest education reforms attempted by a state in recent years, with a price tag that runs into the billions of dollars.

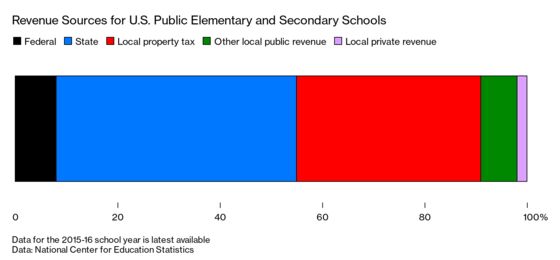

U.S. schools get most of their money from state and local authorities. The latter typically rely on property taxes to raise revenue and can do it more easily in wealthy neighborhoods. It’s a “uniquely American” system, says Elaine Weiss, a researcher at the Economic Policy Institute. And its distributional consequences are “uniquely bad,” she says. “Some kids, just by dint of where they are born, will have much less funding.”

In this year’s legislative session, Maryland lawmakers are considering a proposal that would ramp up education spending by state and local authorities, adding $4 billion a year by the end of the decade. The goal is educational outcomes—and ultimately social and economic ones—that are both better and fairer.

The commission that drafted the plan said it wants to transform a school system with “glaring gaps in student achievement based on income, race, and other student subgroups.” Less than half of Maryland kindergartners enter school prepared to learn, the commission said, and tests show only about a third of the state’s high school juniors are “college and career ready.”

William Kirwan, the commission’s head and a former University of Maryland chancellor, calls the under-education of vast segments of the U.S. population a “ticking time bomb” that’s “right there hidden in plain sight.”

The Kirwan proposal is based on a reality that McCauley experiences every day in Crellin: Kids are walking into classrooms with problems and won’t learn much unless those are addressed. It envisages full-day prekindergarten for children as young as 3 years old, an expansion of family support centers, and improved pay and career paths for teachers. Schools with a high concentration of poverty would get counseling and health services.

Maryland’s state government would pay for a chunk of the program—and play a redistributive role, directing more money toward poorer areas, such as Garrett County, where Crellin is. By 2030 state spending would rise $2.77 billion above the current law while local funding would rise by $1.23 billion.

Paul Edwards has been a mayor, teacher, and coach in Garrett County, where his family has lived for four generations, and now is a county commissioner. It’s going to be “very difficult” to find the money for the proposal, he says, because Garrett recently raised taxes and is worried about chasing residents and employers away. With companies relocating across borders in search of lower costs or into areas that have a technologically skilled workforce, keeping jobs in rural areas is a high priority. He also acknowledges the flip side: The biggest challenge for new business in the county is finding the right workers, and education is vital for that.

The Maryland educators’ union, which is backing the Kirwan plan, makes the same point. It argues that the only way to stem population decline in such places is to make them attractive to employers, which means having an above-average school system. The union also says Garrett County will get more money in state aid than it has to pay from its own coffers.

The county’s profile illustrates what millions of Americans are missing, even after a decade-long economic expansion left the country better off on aggregate. Unemployment in Garrett is just 4.2%, but taxable incomes are among the lowest of Maryland’s 24 counties.

While income inequality across the U.S. has steadily worsened, the performance gap between rich and poor students has at least stopped widening, says Bruce Baker, a professor at Rutgers University who specializes in education financing. “In a modest way I guess that could be called a win,” he says, but it’s going to take a lot of time and resources targeted to high-need districts to narrow the gap. “Some of these states are trying to lean hard” against inequality, Baker says. But “they’re leaning against a very strong force.”

Kirwan, who’s 81, says most people his age have retired and left political battles to others. But as a lifelong educator, he’s worried—and not just about his own state. “We have these horrific income gaps in America,” and educational disparities are making them worse, he says.

He anticipates a pitched battle as the state legislature begins debating the plan that bears his name. “Who knows if we are going to get it across the goal line,” Kirwan says. Yet he’s hopeful that if it does pass, “it will be a drop of a pebble in a lake that could ripple across our country.”

Read more: How Much Money Do You Need to Reach the 1% in America?

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net, Ben Holland

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.