How to Retire Now-ish: A Guide to Inflation, Rising Rates, and More

How to Retire Now-ish: A Guide to Inflation, Rising Rates, and More

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- After years of watching strong markets swell portfolios, many recent and would-be retirees are in a nice spot—on paper. But it may be an awkward and anxious moment emotionally. The assets that sent account balances to such heights—particularly a handful of big U.S. technology stocks—now look expensive by many measures and have been showing some weakness this year. At the same time, reducing your exposure to stocks feels dangerous with inflation running at the highest rate in decades, eating away the modest returns of more conservative investments. And with the rise in interest rates seen by many as just getting started, bond funds look vulnerable to losses.

“There is definitely a lot more strain now for retirees,” says Wade Pfau, a professor at the American College of Financial Services in King of Prussia, Pa., which trains financial planners and advisers. “We are outside of all the historical situations that we have been talking about for retirement.”

After months of predictions that inflation would be transitory, the Federal Reserve’s recent sharp pivot to being concerned about it may be the start of an unmooring of interest rates from historically low levels. While annual yields on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds are hovering near a two-year high at about 1.86%, that’s far from the 6% average back in the early 1960s. Bond prices fall as rates rise, so even the safest fixed-income investment may be in for a relatively rocky ride. Higher interest rates will also mean higher yields from bond funds—and they’ll eventually show up as higher rates in certificates of deposit and money-market funds as well. But the hit to bond funds is immediate.

A subpar performance for stocks could have big repercussions for recent retirees. “We have had a tremendous run in the stock market,” says David Blanchett, head of retirement research for PGIM, the investment management group of Prudential Financial. These gains may have encouraged people to retire. “The problem is after markets have done well, they tend to do poorly.” He sees “a very good possibility” of a market correction in the near future “or just lower-than-average historical returns.”

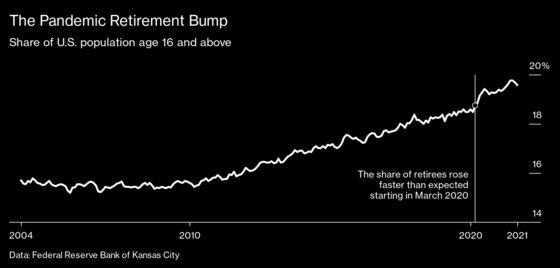

It’s not all grim. Investor portfolios have grown bigger and faster than most people would have anticipated, making retirement more feasible. (There’s been a larger-than-expected bump in baby boomer retirements, which is likely due to Covid disruptions and health risks as well as asset gains.) Also, the average U.S. homeowner gained $57,000 in equity by 2021’s third quarter from the previous year, according to CoreLogic data. So for most people this isn’t a time to radically shift gears on a retirement plan.

But it’s a good time to reassess portfolios and assumptions about spending in retirement. New retirees and near-retirees can sometimes be a little complacent about how much risk they can tolerate. They’re old enough to have lived through a few market cycles and tend to be more comfortable with equity risk, says Christine Benz, Morningstar Inc.’s director for personal finance. “They start thinking they don’t ever need to de-risk, because you know the market is volatile, but then it comes back,” she says.

But the situation in retirement is different. While those still working can ride out volatility as they add money to their savings, those who are hit with a string of stock market losses early in retirement can see their portfolio permanently hobbled, especially if they’ve been taking withdrawals. Even if markets rebound, the gains come on a diminished pot of savings. “As you start drawing down money in retirement, it becomes less of an intellectual exercise and a real challenge,” Benz says. “Because if you don’t have enough liquid assets to draw upon then, your only choice is to tap depreciating assets.”

One way to address this risk is to scale back spending assumptions, at least initially. The so-called 4% rule, a longtime rough guide for how to draw down cash in retirement, may be too aggressive at the moment. The idea was to take 4% of your assets out in your first year, then take the same dollar amount, plus an increase to match inflation, in subsequent years. Studies had shown that a retirement nest egg would very likely last a lifetime at that rate. “That was based on 30 years of all the different markets going back to the 1920s,” says Pfau, the professor at the American College of Financial Services. “But interest rates are now lower than they ever were at the start of retirement historically; market valuations are as high as they ever were in that history.” Many retirement experts have whittled down the 4% rule to 3% or 3.5%.

You can add protection by using a “bucket” strategy, where you think of your savings as split into different buckets based on how soon you’ll need to access the cash. The far-off buckets can be allocated more aggressively, while money to cover expenses coming up in the next year or two goes into short-term bonds or cash. That way you’ll avoid selling stocks when the market is down, Pfau says.

There’s a chance that you’ll lose money on bonds as well, but Benz thinks investors should keep that in perspective. “Thinking about the magnitude of losses you’re likely to experience in high-quality bonds, even in a rising rate environment, it’s going to be much less than the loss you would have in the equity portion of your portfolio,” she says.

One way to ensure that you won’t outlive your money, and to get built-in inflation protection, is to delay claiming Social Security until the age of 70 if you can afford to. This doesn’t necessarily mean you have to work that long. People should be willing to spend retirement assets to delay taking Social Security, says William Bernstein, co-founder of investment management firm Efficient Frontier Advisors. For every year past full retirement age, which is 67 for anyone born in 1960 or later, your benefit goes up by 8%. Social Security comes with cost-of-living adjustments, which also apply to the years you delay. “The Social Security trick goes a long way toward immunizing you to living to 100,” Bernstein says.

Tweaks also can be made to a portfolio to offset inflation. One of the best: buying I bonds, which are U.S. government-issued bonds with a rate—currently 7.12%—that resets twice a year based on inflation. An individual can buy only $10,000 per year, but they can purchase an additional $5,000 using their federal income tax refund. Other classic inflation hedges include Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS), which are also available through funds and real estate.

To diversify, retirees may want to add foreign stocks. “We’ve had fat years for investing in U.S. vs. foreign stocks, but foreign stocks’ expected returns are higher, because they are cheaper,” says Bernstein. He figures that 30% of a stock portfolio could be in foreign holdings. PGIM’s Blanchett also likes the idea of making sure retirees own stocks beyond the usual large-cap U.S. stocks and suggests a stake in small-cap stocks as well.

The idea isn’t to yank all your money out of the S&P 500—that kind of market timing is almost impossible to get right—but to ensure that you aren’t overloaded in assets that have done so well for so long. “Retirees need to be careful to not use the past 10 or 15 years as a lens for how to position themselves going forward,” Benz says.

Read next: Why People Are Quitting Jobs and Protesting Work Life From the U.S. to China

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.